I try to keep my cranky old man opinions about entertainment to myself. I try, I don’t always succeed — I did just write 1,400 words shitting on a long-forgotten rom com from the ‘90s. But I mostly bite my tongue. There is no old man opinion crankier than “entertainment was better when I was young,” except perhaps “kids these days don’t know anything about the world,” and that second opinion makes up 80 percent of the content on this blog.

But…I do think that TV, music, and movies used to be better. Sturgeon’s law — that 90 percent of everything is crap — has always been true. But I wonder if our crap quotient is currently edging towards the high 90s. In comedy, especially, I’ve noticed that most of the big, bankable stars were big, bankable stars 15 or 20 years ago. With the important caveats that: 1) “Good” is subjective, and 2) I am a 43 year-old crank with a typically sad affinity for the comedy and other entertainment of my youth, let’s at least consider the possibility that a generation of up-and-coming entertainers is sort of missing.

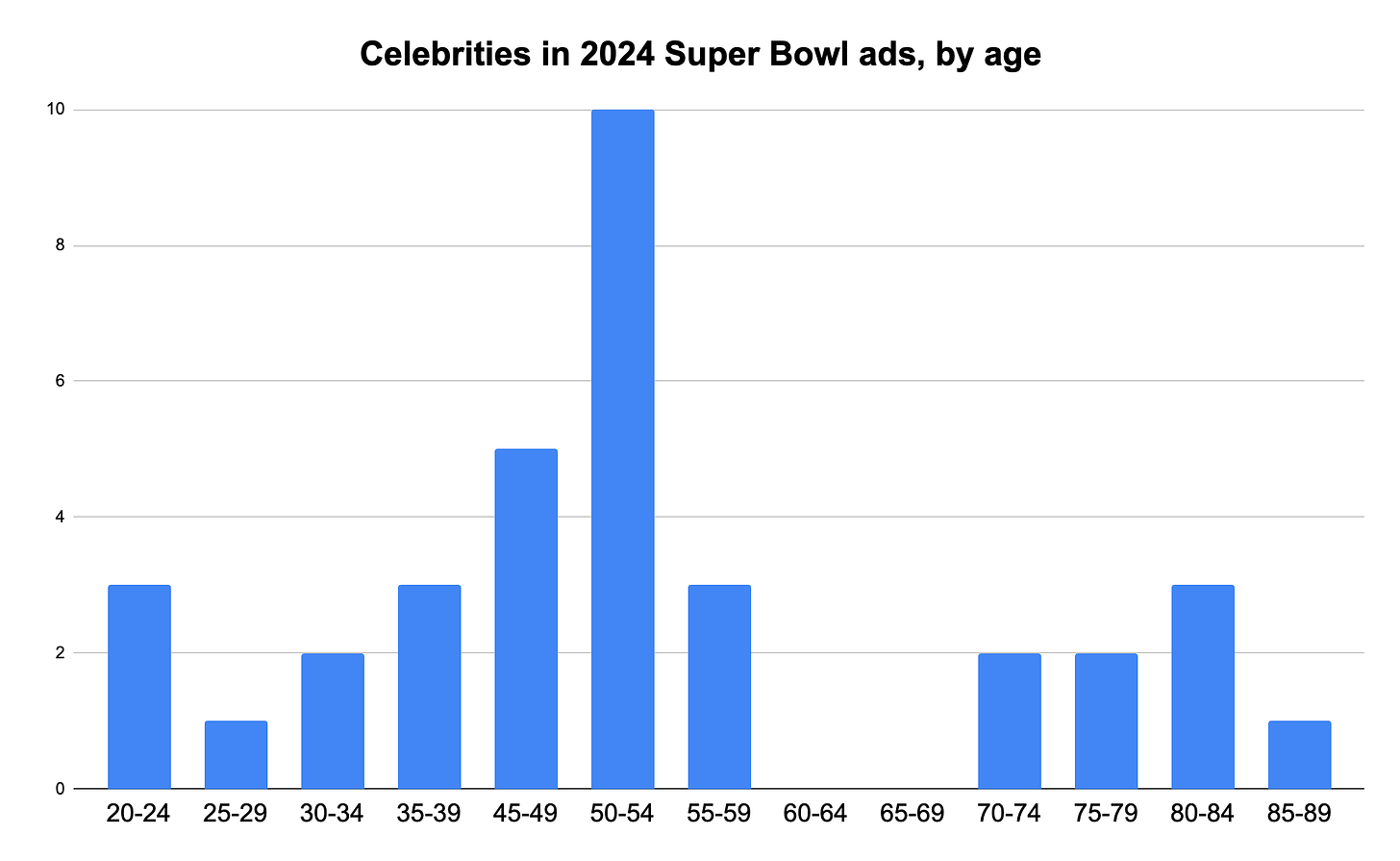

Consider the Super Bowl ads last week. Did you notice that most of the celebrities in those ads were at an age at which opening a TikTok account will get you placed on an FBI watch list? The ads — much like the halftime show featuring Usher and the We Were Your Ringtone In 2004 Players — were pitched at me and my peak-earning-years cohorts. Which might present a chance to test my Missing Generation Theory. And, of course, using celebrity Super Bowl ad appearances as a proxy for the general state of entertainment is an extremely rough measure — I mean extremely rough, like using google searches for “how to write a screenplay” as a proxy for cocaine use. But it’s probably about as good of a measure as we’ll get. I combed through this recap of the ads1 and crunched some numbers: The average celebrity age was 51, and the median age was 50. Here’s the distribution:

Some notes. First, I got the celebrity ages from Wikipedia, which — if Hollywood managers are doing their jobs — should be a den of filthy lies on this topic. The real numbers actually probably skew a bit older than what you see above. Also, the age 20-39 demographic supports my theory that we have fewer young comedians than we should more than meets the eye if you dig into the data. The three stars aged 35-39 — Michael Cera, Aubrey Plaza, and Scarlett Johansson — were famous 15 years ago. That leaves 34 year-old Quinta Brunson as the only young comedian on the list who got famous post-2009.2 Compare that to the 40-59 cohort: 12 of the 25 people on that list are comedians, and another six are actors known mostly for comedy (e.g. Vince Vaughn, Ryan Reynolds). So, yes: It looks like the people who make us laugh are overwhelmingly in their 40s and 50s and mostly made their name 15-20 years ago (or longer).

Let me reiterate: This is the absolute crudest of measures, Super Bowl ads probably favor a certain type of celebrity, and quantity is not the same as quality — all of that is true. But this exercise certainly doesn’t contradict my theory that the next generation of comedians and other entertainers is notably sparse.

If there are fewer entertainers in their 20s and their 30s than there “should” be, then why might that be true? Here are some theories:

The early pipeline has gotten worse. Social media is now many people’s entry point to an entertainment career. I see three huge problems with that: 1) Social media will always favor pretty girls; 2) Social media will always favor people who have the inclination and resources to promote themselves at least as much as it favors people who make good stuff; 3) Young people are morons who don’t know what they want.

You may quibble with point number three, but very few people who work in entertainment would quibble with point number three. Young people are a notoriously fickle and inscrutable audience; fortunes have been lost trying to read their gelatinous little minds. If you let young people do all the sorting — instead of letting them choose from a few pre-sorted options — then they’re likely to up-vote nonsensical crap with no broader appeal.

Improv has also become the dominant real-world entry point to comedy, displacing standup and sketch. This greatly advantages wealthy, theatre kid-types, because: 1) You have to take a bunch of expensive classes; 2) You’re expected to be part of a culture that’s only possible if you’re free to not make any money in your 20s, and 3) You have to be able to tolerate wealthy theatre kid-types. That third thing is the deal-breaker for scores of people. I’ll write a whole article about this phenomenon at some point.

The middle pipeline has gotten worse. Late night shows don’t have stand up comics on anymore. Micro-budget cable shows for comedians who might be on the cusp like Best Week Ever, Standup Standup, and Evening at the Improv have disappeared. Cable is dying; Comedy Central is almost entirely Seinfeld and Futurama reruns now, and The Daily Show effectively passed over its correspondents and went back to Jon Stewart. Big roles on SNL these days often go to celebrities (hat tip to James Austin Johnson for bucking that trend). There are just fewer opportunities for comedians who have a bit of heat to broaden their appeal.

There are fewer opportunities in the big-time. The trend in movies is towards making fewer movies that are bigger hits; that squeezes out anything that’s not a blue chip franchise. That trend, along with the increasing importance of foreign markets, is probably why there are many fewer comedy movies than there used to be.

Comedy TV has also fallen on hard times: None of the top 100 individual telecasts in 2022 was a comedy, and the only comedies to crack the top 30 in average ratings in ‘22-’23 (these numbers aren’t affected by the strike) were Young Sheldon and Ghosts. Streaming “comedies” are typically dramas mislabeled as comedy, and the only one that anyone really watches is Ted Lasso.

These trends increase the value of bankable, blue chip stars and make studios less likely to roll the dice on a no-name. If you’re making one comedy movie this year, do you cast Ben Stiller, who has been in many hits, or do you cast Johnny TikTok, who has two million (extremely stupid) subscribers? If you’re making one TV show, do you gamble on a strong script from a no-name, or do you reboot/spin off something that’s already been proven to work? And before you answer, consider that if you go the Ben Stiller/reboot path and it doesn’t work, you can probably say “the marketing was bad” and keep your job. But if you stick your neck out with a no-name and the project flops, then you’re almost certainly fired.

Identity is displacing talent. Race, gender, and sexual orientation are part of most decisions in Hollywood these days. Entertainment publications and social media track race and gender the way investment bankers track market trends, and companies trumpet the extent to which identity is part of their decision-making process. Of course, the more that any factor other than “ability to do the thing” is factored into decisions about who gets to do the thing, the fewer opportunities exist for talented people to advance.

And, again, put yourself in the shoes of a studio executive. Imagine that you do decide to throw caution to the wind and gamble on a no-name. If that no-name checks one or several identity boxes, then if the project flops, you can at least say “I was trying to promote (fill in the blank) talent.” You might keep your job. It takes a lot of balls for anyone in Hollywood to say “You shouldn’t have funded that show about a queer Black undocumented immigrant who experiences homelessness.” Better to just bite your tongue, keep your job, and light a huge chunk of the studio’s money on fire.

It’s also not just Hollywood; identity considerations are common in every step of the process. They affect who makes it through the early and middle pipeline. Even a studio determined to hire the best available talent might fail because the farm system (so to speak) isn’t promoting talented people the way it used to.

Society is divided, media is divided. The monoculture is dead. Media has shattered into a million pieces, and each of us can watch what we like instead of having our options limited to M*A*S*H, Three’s Company, or stare at the wall. This divergence in media consumption drives further divergence in taste, which drives divergence in media consumption, and so on and so on until I genuinely start to worry about our societal health.

Media has been Balkanized, but a big star needs to have broad appeal. How can an up-and-coming star be seen by enough people to become famous outside of a narrow, bespoke audience? It’s tough, bordering on impossible. That gives an leg up to stars who made their name back when shows like Friends and The Office drew gigantic numbers.

Are you buying any of these theories? Or possibly all of them — they’re not mutually exclusive. Or maybe you disagree that there are fewer young celebrities than there should be. If that’s your position, then you might be right — it’s hard to keep my cranky old man-ness from skewing my perception. And yet, until I see evidence otherwise, my opinion remains that we had real entertainment back in my day, and all we have now is falderal and useless flummery.

I only counted celebrity cameos in the ads, not the non-celebrity actos. Also, if a celebrity wasn’t mention in the Times article, then they didn’t make my list. And I didn’t count athletes because we are objectively not missing a generation of athletes.

To be fair, I should mention that three comedians on the list — Kate McKinnon, Dan Levy, and Heidi Gardner — are all 40 and all got famous within the last 15 years. Though, to also be fair, Kate McKinnon was famous ten years ago, Dan Levy is the son of a comedy legend, and Heidi Gardner was in those Apartments.com ads as an actor, not as Heidi Gardner. So, it still appears to be hard to find a way in these days.

Have you noticed one of the top comedy cliches for Millennials and Gen-Z are 90's sitcom parodies?

I'd also add that younger people are being prevented from experiencing great art (pop or otherwise) from the past as inspiration. A combination of having a non-stop glut of "new" content and the shielding-from difficult or problematic material from the past. With three networks and some UHF stations to entertain me as I child I was exposed to all kinds of pop-art and entertainment from the 1940's on. I came home from church on Sunday in the mid-80s to be greeted with Little Rascals and Three Stooges shorts on television.

To me this deficiency is most visible in the drop off of Pixar and Disney storytelling, and the audience reaction to it.

Particularly in art, the ability to fail and grow is important. With all young comedians' content available for all the world to see and there in perpetuity, I wonder how many fledgling comedians had their career end before it even began because of something that would have maybe gotten them booed in a nightclub in the 90s, but wouldn't have become attached to them the way it does today.