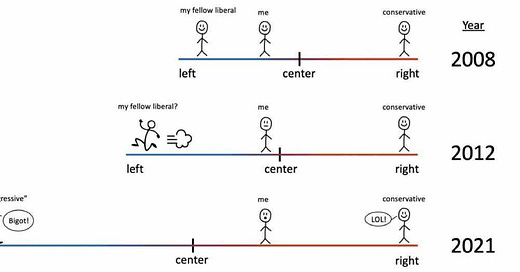

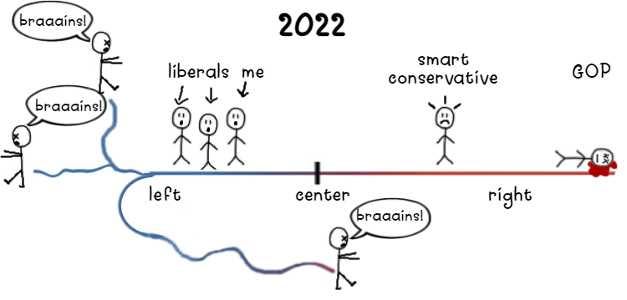

Recently, Elon Musk — a man I simply can’t get myself to care about — tweeted the cartoon shown above. It got a lot of attention, and I understand why; it’s hard to deny that something is happening on the left. I thought about the stick figures for frankly way too long. It was hours — I eventually started to feel like I was pondering the allegorical subtext of a Marmaduke cartoon.

People who are far better at political analysis than I am have looked at what data exists to try to determine if progressives/liberals/whatever have moved left in the past decade. Matt Yglesias and Milan Singh looked at party platforms, and David Shor and Philip Bump weighed in. The consensus seems to be that the left is somewhat more left. Of course, this is tricky analysis — after all, who counts as “the left”? Which opinions matter? What does “moving left” even mean? These are all fair questions, but rather than let them bog down an otherwise interesting discussion, I prefer to wave them away with the wise words of a mostly-naked Will Ferrell, who asked: “Why are bushes bushy? If we’re going to get into that area, we’re going to be here all day.”

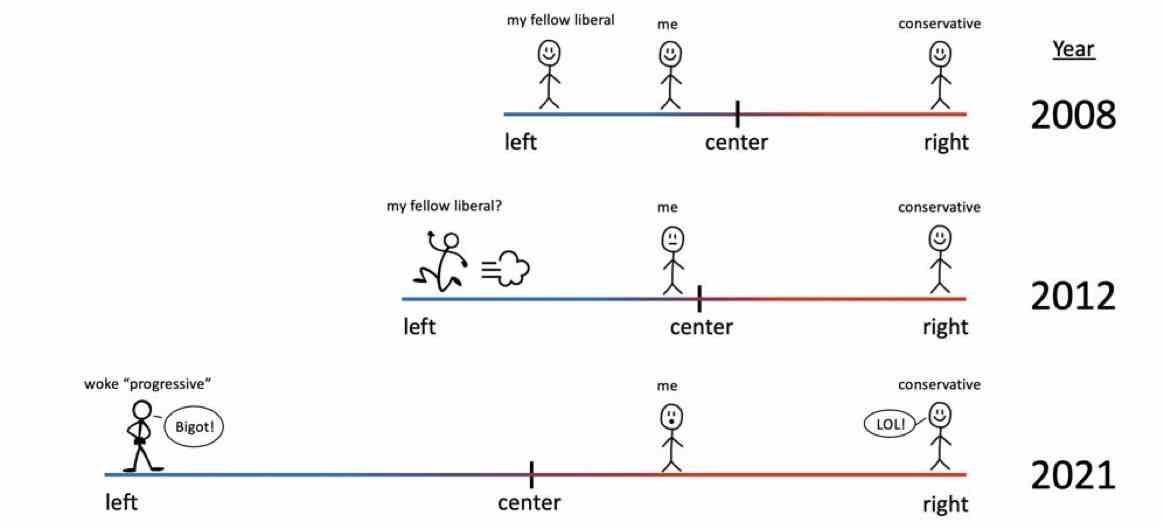

I think the cartoon represents something real. But I also think it’s missing some context. What follows is the cartoon as I would draw it, in which I look to objective metrics as much as possible but in which I am — admittedly — going largely by feel. This is one person’s perception, take it for what you will.

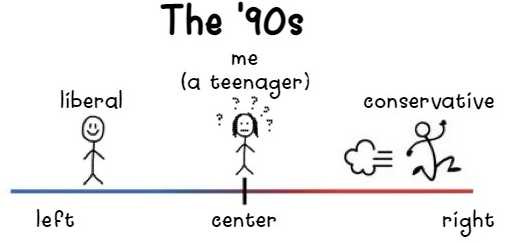

Panel 1:

Did you know that there used to be a thing called a “Northeast Republican”? It’s true; they could be found in New England and were usually the villain in National Lampoon movies. They were very into boats and shirts with little logos on the left breast. They liked church, and not the life-affirming kind of church where you wear a fun hat and sing upbeat songs; they preferred the dour type of church where you read pre-written prayers and apologize to God for your genitals. They were horrified by all things “improper”; they were incensed by Jimmy Carter’s Mr. Rogers-casual attire and turned on Nixon when he was shown to be a rule-breaker and a pottymouth. They weren’t really fire-breathers on race, and were integral to passing the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act.

George H.W. Bush was the quintessential Northeast Republican. He ended up being a divisive figure in the Republican Party; writers including Geoffrey Kabaservice and E.J. Dionne have chronicled the intra-GOP revolt that happened in response to Bush 41’s not-conservative-enough-for-some presidency. After Bush lost, the newly-ascendant right won big in the 1994 midterms, which was dubbed the “Gingrich Revolution” (by Newt Gingrich, at least). The GOP made Rush Limbaugh an honorary member of the ‘94 Republican freshman class, which is kind of like showing up to a date with a bag full of condoms and sex toys: You’re making it perfectly clear where your head is at and what you’re hoping to do.

Between 1995 and 2015, the proportion of Republicans who call themselves “very conservative” went from 19 percent to 33 percent. Other measures note a rightward shift around that time. Republican office-holders in the Northeast and West Coast mostly disappeared. To a large extent, the shift seems to have been caused by demographic sorting and the disambiguation of the parties that happened as Dixiecrats disappeared.1 But the efforts of conservative activists who captured the Republican Party also played a major role, which is about as close as I’ll get to giving Newt Gingrich credit for anything.

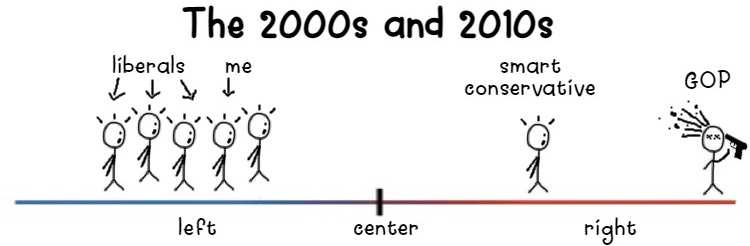

Panel 2:

In the 2000s, Fox News became a behemoth. Conservative radio proliferated as Clear Channel Communications bought up stations across the country. Conservative bloggers like Matt Drudge and Erick Erickson gained influence. The right-wing dream of a conservative media ecosystem that had existed at least since those meddling kids Woodward and Bernstein got everyone’s knickers in a twist over Watergate had finally arrived.

Journalism is ostensibly about the truth. Journalism’s platonic ideal — waxed about constantly in Oscar-bait movies and West Wing monologues — is an unvarnished presentation of reality. Cronkite’s famous sign-off was “and that’s the way it is”, not “and those are the parts we thought you’d like — I hope you had fun.” Cronkite’s sign-off had a distinct air of “like it or don’t like it, I don’t really give a shit”, which I think is fantastic.

Conservative media took a different approach: What if you decided what the world was like before you gathered the news, and then just reported the bits that fit that narrative? It was a game-changing approach, similar to Jack Donaghy’s suggestion that comedy writers start with the catch phrases and work backwards. And it worked, in terms of gaining viewers. Unfortunately, it’s probably more responsible than any other factor for the near-total brain death of the Republican Party.

The writer Tim Urban thinks that viewing politics along a simple, left-right continuum is incomplete. He thinks that we need to consider not just what we believe, but why we believe it. He takes the traditional left/right political spectrum and uses it as the x-axis of a graph that also has a y-axis. The y-axis charts the push-and-pull between the so-called “primitive mind” and “higher mind”. The primitive mind is the impulse we all have to look out for our immediate needs and safety; it’s short-sighted and selfish, and it specializes in identifying “bad guys” and slaying them. The higher mind represents our more reasoned and broad-minded tendencies. Politics tends to speak to the primitive mind, and of course it does; we spent millions of years evolving those habits, and the idea that you shouldn’t immediately kill your enemies with a rock is a relatively new and edgy concept. Urban ends up with a graph that looks like this:

In the 2000s and 2010s, the Republican Party came to appeal mostly to the bottom-right quadrant of that spectrum. Driven largely by right-wing media, the GOP’s animating force became a desire to own the libs. Policy became perhaps a fourth or fifth-order concern, which explains why the Trump administration had no major policy goals other than to be Bizarro World Obama, and why the 2020 Republican Convention produced no platform. Dominating liberals is now such a high priority in the GOP that hinting that you’ll ignore the results of a democratic election is treated as a sign of party loyalty instead of as obvious authoritarianism.

I consider the Republican Party to be totally incapable of solving problems. I think they’ve become that way because conservative media has distorted their worldview so badly that they’ve lost the ability to even recognize problems. This bothers me; I’ve never identified as a conservative, but I see the value of the conservative philosophy. There should be someone in society who defends what’s already working and doesn’t fall for every half-baked idea produced by pot-fueled rap sessions in freshman dorms. The world needs a discerning and principled counterbalance to the occasionally-very-stupid ideas of the left. The fact that the GOP can no longer perform that function worries me a lot.

Panel 3:

Now we’re in the era addressed by the original cartoon. And I agree: Something happened. Much has been written about this, including on the left. This panel is my attempt to capture the fact that I think what happened was a bit more complex than simply “the left moved left”.

A new ideology has invaded the left. Nobody quite knows what to call it; a lot of people say “woke”, Wesley Yang calls it the “successor ideology”, I say “religious left” because it reminds me of the religious conservativism I grew up with. In this drawing, I’ve depicted it as a zombie to convey that I think this is something coming from outside; this isn’t “what was there before, only moreso”. This is something foreign — more on that in a bit.

Why did things change when they did? I think it probably starts where the conservative story started: with geographic sorting. Blue parts of the country are bluer than they used to be, and economic stratification has overlapped with economic polarization. Depending on what circles you run in, you can go a long time without encountering someone who thinks differently than you. The world I was recently in — late night political comedy — was far enough left to make your typical Vermont art collective look like a Proud Boys meeting. And, of course, ideologically homogeneous environments lead to groupthink; they’re basically human growth hormone for bad ideas.

I also think the liberal media landscape now more closely resembles what conservatives built. Mainstream outlets have changed due to the exodus of their conservative audience and by the rise of engagement-based business models. MSNBC is neither as popular nor as terrible as Fox News (it would probably be more popular if it was more terrible), but it sucks a lot and is part of the landscape. To my eternal regret, I think that late night political comedy shows played a role in the change. And, of course, there’s Twitter; Twitter is much younger and farther left than the population, and it includes every journalist in America (it’s part of their job now!). Therefore, journalists are far more likely than other people to think that Twitter is real life. We’ve created a clique-y, performative environment that’s ten times worse than the viper pit of high school, and then required the country’s most influential people to spend large amounts of time there.

This is the environment in which a simplistic worldview that sees all things as a zero-sum conflict between oppressor and oppressed has bubbled up. I’m not sure if this view is actually more common than before or just more prominent; it might be that it exists in similar levels as it did in the past, but it gets more attention now. It’s certainly true that Twitter puts you in touch with colossal morons who used to be unable to reach you (what a fantastic service!). At any rate, this view is definitely more influential than it used to be; ideas that used to mostly exist in teach-ins at Antioch College and stage banter from all-female punk bands have gone mainstream.

I think the movement’s focus on race, gender, and other identity issues has made many on the left not quite know how to respond. Ending discrimination based on race, gender, and sexual orientation is so central to liberals’ identity that we’ve become easy marks. Saying “this is anti-racist” to a liberal is like saying “this is anti-fire” to Frankenstein; we’re very likely to buy whatever you’re selling. The appeal to deeply-held values combined with the social penalty for appearing to betray those values has made us slow to call bullshit on spurious charges of racism, sexism, homophobia, or transphobia. And so, the zombie virus has spread.

Panel 4:

I think the left is very much in turmoil. 2020 seemed to be the high-water mark of the craziness, but things are still dicey. I’m far from ready to say that sanity has won out; after all, there was a moment in 2013 when it looked like Republicans were going to tack towards the center, and we all know how that went.

The main thing I want to communicate with this panel — the things I’ve been feeling most strongly recently — is that this ideology is NOT LIBERAL. Nor is it “progressive” or “left”, according to most definitions. I think that a closer look at this way of thinking reveals it to be completely antithetical to the American liberal/left tradition.

As many people have pointed out: This trend is clearly not liberal. Liberalism values things like free speech, individual rights, and due process. This new movement sees free speech as a fig leaf for white supremacy, focuses on group outcomes at the expense of individual rights, and replaces due process with Twitter Justice, the only form of justice that makes trial by monkey seem rational and fair. This movement is liberal the way that Blue Velvet is a kid’s movie.

But I would go even further: I often feel that this movement isn’t strictly “progressive” or “on the left” in any substantive way. We use labels — I use labels — like “progressive” and “left” because this is a new-ish phenomenon and we’re struggling to find language that works. But I often think that those words don’t fit. After all: If progressivism has a defining trait, then it must be distributing resources towards the disadvantaged. So why are so-called “progressives” calling for extremely regressive universal student loan forgiveness? Why did they advocate for school closures that were devastating to poor kids well past the point of necessity? Why are they altering the college admissions process in ways that benefit the wealthy and well-connected? Why are they undercutting real wages by pushing ineffective solutions to inflation? Why are they often the tip of the spear in the fight against lower housing costs? This is progressive? The fuck it is — this is idiocy.

I think the bottom line is that this movement is not defined by finding solutions to problems; it’s defined by performative flailing against perceived enemies. Every issue I listed above is a crusade against someone or something on the lefty enemies list, be it greedy developers, evil corporations, or the omnipresent “white supremacy”. The fact that the impacts of this movement’s actions would often hurt the disadvantaged doesn’t seem to phase its believers. And I think that’s telling: They don’t look beyond the glorious fight against their evil enemies, because the glorious fight is the end goal.

Ultimately, this viewpoint bears some similarity to the movement that destroyed the GOP’s ability to solve problems. Any consideration beyond the Manichean struggle against The Evil Ones has been jettisoned; this is the primitive mind reveling in its element like a pig in a pile of shit. There is no quest for a more perfect nation, only the battle between the righteous and the wicked. This movement is trying to gain influence, and they’ve scored a few victories. If they capture the Democratic Party the way that brain-dead pugilists captured the GOP, then I think we’re in big trouble.

If you’ve ever wondered why the I Might Be Wrong logo is a man falling through space, here’s why: When I started this blog in mid-2021, I was feeling extremely unmoored. Institutions I had depended on were changing in ways that seemed to betray their core principles. Or maybe they weren’t: Maybe I was changing and had chosen the wrong touchstones. Or maybe I was deeply wrong about their core principles to begin with, which would bring into question my ability to make judgements about anything. I didn’t know the cause of the change, but I knew the effect: I was feeling lost, blind, with no fixed points of reference, just spinning, spinning, spinning through space. Much like the guy in the picture. And, as you may have guessed: He’s yellow because I wanted to invoke that scene from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

In the past year, I feel like I’ve gotten my bearings back a little bit. The main way I’ve done that is by: 1) Realizing that many people feel the same way I do, and 2) Gaining what I think is a slightly better understanding of what’s going on. That understanding is basically what I’ve outlined in this post; maybe the story feels familiar to you. I’m sure it’s imprecise and full of holes; if you have thoughts, please share them in the comments (this prompt was probably unnecessary). But one thing we know is that — as proved by the popularity of the stick figure meme — one thing that’s happening is that a lot of people are wondering what’s happening. Hopefully, talking things through will help some of us reorient ourselves and get back to focusing on progress.

It’s fair to ask: “If this is driven by disambiguation, then why didn’t the same thing happen to Democrats?” I’ll address this question later in the article; part of my answer is “it eventually did happen”. But I also think that the rural skew of the Senate and electoral college requires Democrats to compete in reddish areas, which acts as a partial brake against polarization.

I wonder whether the secularization of America has robbed the left of a critical mass of people like Jeff and me, who grew up in conservative religious households, and so have a learned distaste for hypocrisy and sanctimony.

The "In This House We Believe" yard signs generate in me the same queasy feeling I had about the "Heaven Bound" T-shirts my youth group wore to the annual Christian youth conference in Nashville.

(It's a somewhat different kind of queasy feeling than I the one I still get when I think about listening to Amy Grant and Stryper.)

I take a different perspective on the liberal/progressive divide. Namely, modern "progressivism" has never been "liberal" in the classical sense, and instead has its roots in the movement of the same name from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This movement supported some good things (women's suffrage, treatment of juveniles as different from adults) and some bad things (prohibition, WWI, eugenics). Here I recommend: Thomas C. Leonard. (2016). Illiberal reformers: Race, eugenics, and American economics in the Progressive era. Princeton University Press.

I think it is too narrow to say that progressivism's "defining trait" is "distributing resources towards the disadvantaged." (Admittedly, helping the poor has always been one of their goals for reshaping society, beginning with their understandable horror at deplorable urban conditions in the late 19th century.) Progressivism's defining feature is more like "directing society toward 'utopia' through social reform [engineering] guided by 'science'." In contrast to liberals, progressives thought "individual rights" often got in the way of this mission. (In 1913, Dean of Harvard Law School Roscoe Pound argued that the Bill of Rights “were not needed in their own day, [and] they are not desired in our own"; later, (Progressive) President Woodrow Wilson would refer to inalienable rights as “nonsense" [Leonard, 2016, p. 25].) As Jeff points out, Progressivism has always been very "religious" as well: "The progressives’ urge to reform American sprang from an evangelical compulsion to set the world to rights, and they unabashedly described their purposes as a Christian mission to build a Kingdom of Heaven on earth” (Leonard, 2016, p. 12). So, 100 years ago Progressivism was actually religious. Today, it's the secular religion of the Left.

In terms of philosophical legacies, I think you see the roots of conservatism in Hobbes/Locke/Burke, the roots of liberalism in Locke/Hume/Smith/Mill, and the roots of Progressivism in Rousseau/Mill/Dewey. As noted there is overlap!