The Progressive Narrative on Gentrification is Anti-Progressive

White flight is bad, integration is good

Every liberal/progressive/whatever knows that when the word “gentrification” comes up, we need to make with the head-shaking and disapproving sighs. We performatively grumble at the privileged, insensitive white people (even though we often are white people in a converted loft in Brooklyn or Northeast DC). Personally, I refuse to be outdone when this ritual gets going; I pound my fist against the wall and yell “God, damn it — it’s so unfair!” I’ll summon real tears in a display that would impress Alec Guinness. I once lifted a hundred-pound found-wood coffee table over my head and threw it out a tenth-story window while yelling “I JUST HATE GENTRIFICATION SO MUCH!!!”

I had to! If I hadn’t, people might have thought I was racist!

It’s time to ask: Does this ritual make any sense? Particularly: Does it make any sense if you claim to value things like integration and better economic opportunities for poor people? I don’t think that it does. I think that a close look at what’s happening shows that the thing we call “gentrification” is mostly good (and I promise to unpack that “mostly”), and progressive discomfort with gentrification is causing all sorts of bad outcomes for the people they imagine they’re helping.

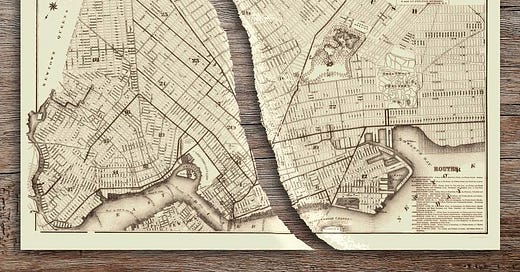

The original sin in the Caligulan orgy of sin that is American housing is white flight. In the ‘50s and ‘60s, white Americans left cities for suburbs in large numbers. They were motivated by affordable housing, racism, better transportation, racism, “good” schools, racism, fear of crime, racism, a preference for a slower pace of life, racism, bigotry, racism, and racism. You may notice that a few of the things in the preceding list that are not “racism” are actually “racism”. At any rate: People moved to the suburbs seeking a better life for their kids, not realizing that their kids would create entire genres of film and music about how oppressive and awful the suburbs are.

You may already notice a logical inconsistency around having opprobrium for both white flight and gentrification. If it’s bad when white people move out of the city, and it’s bad when white people move into the city…where should the white people go? Should they live in hot air balloons, or boats anchored far out at sea? Anyone who’s being serious about housing should have some reasonable answer to the question: “Where should white people live?” And it can’t be “in an Airstream trailer buried deep underground.”

At any rate: White flight led to highly-segregated cities where the non-white parts suffered from low investment and low opportunity. It shouldn’t be surprising that these areas of concentrated poverty came to be associated with high crime and low-performing schools. Let me prove that I’m still a liberal by getting on my high horse for a minute (we love the high horse!): This was a goddamned crime. The institutional neglect of urban centers — which was reflected in transportation decisions and redlining and a million other things — was an inexcusable choice that’s still sending shockwaves through our society. It’s a Jupiter-sized policy fuckup that we should be working hard to reverse.

Gentrification is — in many ways — the opposite of white flight. Of course, people mean different things when they say “gentrification”. Is gentrification just white people moving into non-white parts of town? Is it upper-middle-class people of any race moving in? Is it a change in the area’s “character”, i.e. the opening of the proverbial Whole Foods? Let’s dissect that a bit.

A recent New York Times article demonstrates how muddled the narrative around gentrification is. Hilariously, the focus of the article — the people chosen as stand-ins for the “disappearing” Black population — are two Black homeowners who bought long ago in now-desirable parts of Brooklyn. They’re selling their homes, and we should be crystal fucking clear about something: There are no bigger winners in capitalism than people who bought real estate long ago in New York City. The people in the article aren’t being “displaced” (they don’t claim that they are!) — they’re cashing out. One person in the article — Thomas Holley, who’s lived in Crown Heights for 58 years — is selling his brownstone for about $2 million. Want to see what $2 million gets you near where I grew up? It gets you 7,000 square feet of brand-new beach-front property, 8 bedrooms, 7 baths, pool, jacuzzi tub, vaulted ceilings — Thomas Holley is going to live out his days in a level of luxury that would mildly embarrass a Qatari sheikh. And good for him: He won the New York real estate lottery! Mr. Holley, if you’re reading: Please stop by my place for a high-five on your way out of Brooklyn, because you fucking rule.

So, first thing to note: If redlining was bad (and it definitely was!), then what happened to Thomas Holley is good. If “gentrification” means “increased desirability that attracts investment”, then that’s good for people who OWN property. People on the left often decry the ways that Black people were denied opportunities to gain wealth, and I think that scorn is 100 percent on-point. But the argument goes sideways when you tack on: “And it would be good if places where Black people could accrue wealth were to remain low-investment forever.”

The second thing to note is just how fuzzy the concept of “displacement” is. You always hear that people are being “forced out” — the Times article above traffics in the “forced out” narrative, even though a close reading makes it clear that people are choosing to leave.1 It’s worth asking: How, exactly, would one force someone out?2 Chase them away with a broom? Pull a fake fire alarm? Engage in a Scooby Doo-style plot to dress up like a ghost and scare them away?

There’s exactly one way that people might be “forced out”: Rising rents. When an area becomes desirable, that’s good for people who own property, but it can be bad for renters. This is the part of the anti-gentrification narrative where I’m on board: If low-income people live in a place that suddenly becomes desirable, and rents rise as a result, I agree that that can be bad.

But — in one of those tragically-ironic twists that makes me want to throw myself into an ice crevice — gentrification is often invoked as an argument against policies that would improve that situation. This is Econ 101: When do prices rise? When demand exceeds supply. An area “becoming more desirable” (as I just put it) represents an increase in demand. Prices will rise in the long-term if supply is constricted, so the way to keep prices from rising is to make it easy to build. This is so fucking obvious that I feel stupid even typing it.

But some people don’t get it! Concerns about gentrification are frequently cited to oppose new housing projects. The talking point from the anti-growth crowd is usually “we need affordable housing.” And on one level, sure: Affordable housing is great, I’m for that, huzzah. But how does housing become affordable? As Jerusalem Demsas explains at 44:36 here, affordable housing is almost never built new — housing becomes more affordable as it ages. That is: It becomes more affordable unless there’s a housing shortage, at which point renters get into a bidding war, which the wealthier party is almost certain to win. Some people might respond to that by arguing for rent control, but come on: Rent control has a long record of producing blight and shortages. Rent control needs to be on the master list of “Bad Ideas We Don’t Debate Anymore”, right next to “public stonings increase crop yield” and “sickness is caused by having too much blood.”

It’s remarkable how often anti-growth arguments seem to be pro-blight. It’s true, of course, that rent will stay low if any attempt to invest in an area is rejected. But you know what else would keep rents low? Ending all public transportation to that part of town. Having no good jobs nearby whatsoever. A spree by a Jack the Ripper-style serial killer. A 200-foot tall, centrally-located “community manure pile”. Giving every toddler in the neighborhood a vuvuzela. You can keep rents low by making a neighborhood a terrible place to live, and some people seem determined to pursue that strategy. Of course, if people really want to keep rents low, they should do the obvious and release a million poisonous snakes into the neighborhood. I don’t know why nobody’s tried this; snakes are cheap, and most people don’t like having 500mg of venom shot into their leg as they go for their morning coffee. You won’t have bougie graphic designers bidding up rents if you became the Million Poisonous Snake District.

We need to get our heads on straight: Blight is bad. White flight led to chronic disinvestment, and that’s the trend that needs to be reversed. If we’re serious about desegregation and better economic opportunities, then we need to allow the flows of people and money that cause those things. People in disadvantaged neighborhoods have endorsed this model by voting with their feet: Research by Lance Freeman, a professor of Urban Planning at Columbia University, found that poor people in gentrifying neighborhoods were less likely to move than similarly-situated people in non-gentrifying areas. That’s the headline finding in a paper titled: “Did You Ever Notice That Most of This Dumb Anti-White People Shit COMES FROM WHITE PEOPLE?”3

And that’s the last anti-progressive part of the progressive gentrification narrative: Sometimes, it’s just plain racist. The things people say often remind me of my ex-mother in-law, who was an old Polish lady from Greenpoint, Brooklyn (she probably still is). Her family was a case study in white flight; they left Brooklyn when — according to her — “the neighborhood changed.”

Now, because she was talking about Greenpoint — the only place that could rival Austin for the title of Hipster Capital of America — it could be argued that she was saying: “Too many hipsters.” And if that’s the case: I get it. My…fucking…God — have you been to Greenpoint? It’s a twee trustafarian-verse, an entire culture spawned from a Belle & Sebastian song. A hundred hipsters are undoubtedly worse for property values than a million poisonous snakes. What I’m saying is: I have some small level of sympathy for the “the neighborhood is changing” argument.

But many times, that argument is just racist. Was my ex-mother in-law saying “too many hipsters”? That would be an extreeeeeeeeemly charitable interpretation of her words. She probably meant that too many Black people were moving in, or too many Jews. That’s ugly stuff that no liberal/progressive would support (not openly, anyway). Of course, the “we need to keep out X” sentiment is as old as human history, and some liberals feel the need to make a quadruple-backflip argument about how things are different when you’re talking about non-white communities and white people, because of power and history and Robert Moses etcetera etcetera. Okay, whatever. Personally, I feel comfortable saying that I’m just never on board with the “we must keep out [insert race/ethnicity here]!” argument. I’m opposed to it, 100 percent of the time.

Why is the progressive narrative on gentrification so incoherent, and yet so persistent? To answer that question, I think we need to reflect on what wokeness actually is. I think of wokeness (or whatever you want to call it) as a performative expression of guilt. A person feels guilty about their racial or class advantages, so they unthinkingly side with the disadvantaged group. They do this publicly, because they want assurances that they're a good person. It’s an absolution ritual — a progressive ranting about whiteness on Twitter is the same as a Catholic saying Hail Marys.

The important thing to note about this ritual is that it’s unthinking. The opinion being expressed often isn’t deeply held or understood — it’s just what the person feels they need to say to maintain standing within the group. That’s why someone can express hatred for white flight and gentrification even though those positions seem to contradict. Maddeningly, this seems to be yet another instance of mostly-white people assuming they know what non-white people’s opinions are but being dead wrong — I’ll reiterate that people move LESS when they’re in a gentrifying neighborhood. Also: How dare you deny Thomas Holley his eight beds and seven baths in Virginia Beach. He played the real estate game and won — fuck off, white idiots.

Luckily, I think this circle is extremely easy to square: White flight was bad, gentrification is mostly good. And that “mostly” gets removed when you promote pro-growth policies that benefit renters. The good news is that there are signs that progressive views might be lurching towards logical consistency: California just passed a pro-growth bill that ends single-family-only zoning. It was mostly Democrats who did that — the California legislature wasn't supplanted by Cato Institute insurgents in an unreported coup. We might be headed towards a future in which people in formerly-blighted areas have more opportunities, and in which liberals don't need to engage in an impromptu off-Broadway show demonstrating their disgust every time the word “gentrification” is mentioned.

***Poll for Friday***

I'd like the next column to be about...

1. How there should be more Congressional oversight of drone strikes [VOTE FOR THIS]

2. How the compromises in the reconciliation bill are an example of the overreach of last summer having negative consequences for the poor [VOTE FOR THIS]

The choice to not live in Brooklyn wasn’t just made by Thomas Holley and the other lady — it was also made by their families. Both homeowners in the article offered their homes to their families, who declined. It’s true that buyers of high-end Brooklyn real estate are more likely to be white than Black, so fewer Black people today can “choose” to live in that part of town. So, Black people would have more choices if they had more wealth, which means that you need to let Thomas Holley make a killing on his sweet-ass Brooklyn brownstone, because that’s how wealth accrues.

Historically, there are many examples of people actually forcing other people out of neighborhoods through violence. And not all of those instances are in the distant past — here’s an example of such a campaign in Hoboken in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. But those campaigns are exceedingly rare these days, and they’re clearly not what we’re talking about when we talk about gentrification. Forcing people out of a neighborhood through violence is obviously never okay.

That is not the paper’s title. The title is “Gentrification and Displacement: New York City in the 1990s”. Lame.

A few weeks ago social justice educator I follow on Instagram posted pictures of her parents' old neighborhood and said she sometimes wondered if there shouldn't be a limit on how many white people can move into a neighborhood. (Her family is black, and the area is slowly gentrifying.) I told her I understood that impulse emotionally (for one thing, her father had just died), but to what end?

If we went with the Kendi Equity model, what would happen if a black family wanted to move into an area that already had its roughly proportionate amount of black people? Would they be denied the opportunity to live wherever? "Sorry folks, this neighborhood has enough black people," does not sound like a sentence Kendi would get behind. Which says to me, a lot of this stuff is retributive toward white people.

I get it. I do. There's a lot of historic shame to go around. At what point, though, does the cathartic exercise of "now it's YOUR turn to experience discrimination" end?

When I was emerging from my woke fog, I remember thinking "maybe if what people need is to be able to yell at someone because of their pain, I can be that person. I can take it." Then I realized "this is not a political strategy." There's a difference between healing "spiritual" (as it were) wounds and making fair, helpful policies.

I really agree. It's a problem that many people cannot afford housing in safe, prosperous neighborhoods -- but the solution is to help people afford homes, not to keep crime and bombed-out buildings so a neighborhood remains undesirable. We need to build more housing and provide rent subsidies for those who need them.