SEX! Now That I’ve Got Your Attention: A 2018 Anti-Sex Trafficking Law Seems to be Having Dire, Unintended Consequences

A very I Might Be Wrong visit to the red-light district

It’s publishing 101: If you want traffic, you write about sex. I’ve done some dry-ish pieces on this newsletter; I’ve written repeatedly about infrastructure and tax systems. I’ve tried to balance the stuffy ones out with some light crowd-pleasers about ranked-choice voting and zoning. In the interest of being less of a stick-in-the-mud and a bit more fun, I’ve decided to get a smidge click bait-y this week and write about sex. Specifically: I’d like to discuss the ancillary consequences of a 2018 bill that altered a crucial provision of the 1996 Communications Decency Act.

It’s gonna be steamy!

The chain of events that led us here was started largely by a movie. The film is a 2017 documentary about child sex trafficking called I Am Jane Doe. It’s impossible to not be moved by the story I Am Jane Doe tells; in much the same way Billy Elliot makes you want to go out and dance, and Shape of Water makes you want to fuck a sea creature, I Am Jane Doe makes you want to take to the streets to protest the movie’s villain: Backpage.com. Backpage gets virtually all of the movie’s attention; the pimps who actually trafficked the girls are barely mentioned. Backpage ultimately becomes a movie villain on par with Darth Vader or the rock in 127 Hours.

In 2017, Backpage was the dominant web site for sex work. There were others, including Craigslist -- the site where you could buy a lamp and find someone to eat spaghetti off your crotch all in a single afternoon -- but Backpage was dominant. They were basically the Campbell’s Soup of the sex trade, or it might be more accurate to say that Campbell’s is the Backpage.com of soup. Which is a comparison I’m sure Campbell’s absolutely loves.

To its discredit, I Am Jane Doe makes no distinction between consensual sex work and non-consensual sex work. This is an enormous omission, because while it’s true that Backpage facilitated the buying and selling of non-consensual sex, it also did the same for consensual sex. Of course, some people argue that sex work is never consensual; they say that the person (usually a woman) is only doing sex work because they need the money. This, while true, is also true of every job; I didn’t work at Wendy’s because I had a zest for cleaning grease traps and slapping together C-minus sandwiches -- I did it because I needed the money. In order to believe that sex work is always coerced, you have to willfully ignore the voices of the many women who engage in consensual sex work. Personally, I’m always reluctant to stand in the way of a decision that an adult decides is in their best interest, and that reluctance is multiplied by a factor of ten when applied to a person who might be in an extremely vulnerable situation. That person doesn’t need me -- who really knows nothing about what’s going on in their life -- deciding what’s best for them.

If you’re shocked that a documentary oversimplified a political issue, prepare to be completely blown away by this tidbit: Congress’ intervention was a tad clumsy. The Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations had been reviewing Backpage’s activities even before I Am Jane Doe, and the movie heightened pressure to take action. Hearings included truly harrowing testimony from families of girls who had been trafficked into sex. Hearings did not include testimony from consensual sex workers, and of course they didn’t: Prostitution is illegal everywhere except Nevada, the state that’s built an economy on things the other 49 states pretend not to be interested in. It’s also surely true that Senators didn’t want to appear sympathetic to, for example, a dominatrix who makes money pouring cayenne pepper down a man’s vas deferens, even though there’s probably someone somewhere putting herself through law school that way. Long story short: Consensual sex workers had no voice.

In 2018, overwhelming majorities1 in Congress passed the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, or “FOSTA”,2 which President Trump then signed into law. The law amended Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. You hear a lot about Section 230 these days; whenever members of Congress want to gain leverage over tech companies, they threaten to amend Section 230. That’s because Section 230 provides crucial liability protection for any site that relies on user-generated content. Section 230 is vital enough that it’s been called “the 26 words that created the internet,” though if you told me that there are 26 words that created the internet, I’d have guessed that those words were: “I’m tired of going to a movie theatre every time I want to watch a porno -- isn’t there some way we can solve this with computers?”

FOSTA removed Section 230 protections for web sites that host ads for sex work, whether consensual or nonconsensual. It effectively shut down Backpage and Craigslist Personals3 -- those sites no longer exist. So, huzzah: Those sites are pushing up daisies in the internet graveyard next to Pets.com and Friendster.

But wait…wasn’t there something in the mix at some point about helping women? How did that turn out? It’s been three years: What do we know about FOSTA’s effects?

To answer that question, we need to make the distinction that I Am Jane Doe didn’t: We need to separate consensual sex work from non-consensual sex work. That’s a crucial division in this case, because consensual sex workers and women who have been trafficked into sex have interests that might not align. Of course, I don’t want to perpetuate the myth that most sex workers are empowered entrepreneurs making six figures; that’s an archetype that mostly only exists in Julia Roberts movies and Elliot Spitzer depositions. Many sex workers are in desperate situations. But, I’ll reiterate: The last thing a person in a desperate situation needs is my upper middle-class ass riding in and saying “I know what’s best for you!” I accept their choices as valid.

It seems pretty clear that FOSTA has hurt consensual sex workers. The main way we know that is that that’s what they’re telling us. Here are some quotes from sex workers, taken from a sex worker-led survey4 about the effects of FOSTA:

“I lost all my income, lost my clients and was forced to go back to working a 9 to 5 job that is ableist and doesn’t accommodate my disabilities/health issues. Sex work gave me freedom and flexibility before I lost it all.”

“Was bringing in plenty of income pre-FOSTA. When BP went down I didn’t have a single client for 2 months. My savings dwindled and are now completely gone.“

“My income decreased by 58% in the year following FOSTA-SESTA.”

“I used to make enough to be comfortable now I’m always barely scraping by.”

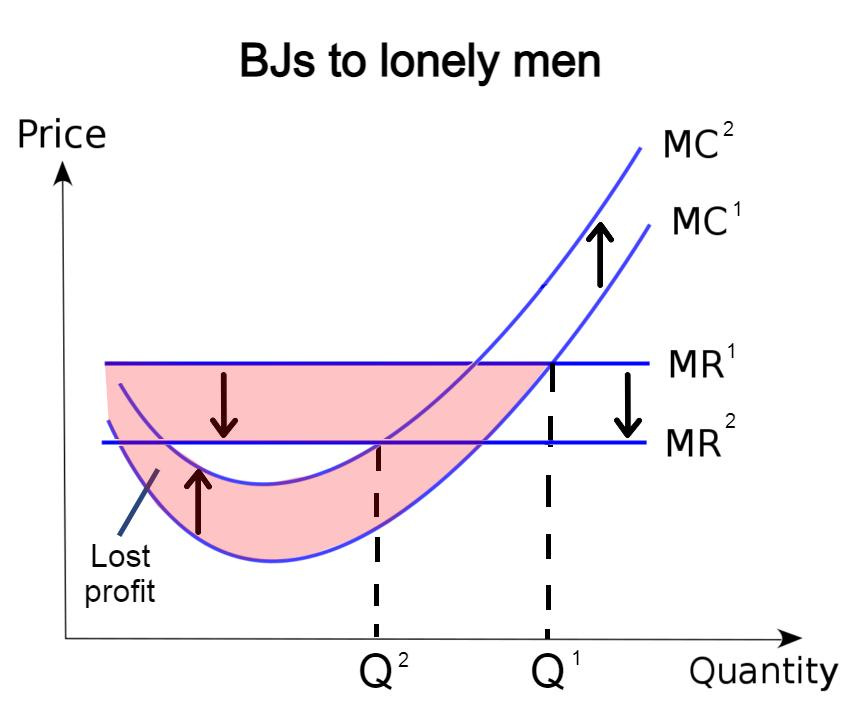

The demise of Backpage created a buyer’s market for sex. Sex workers have scattered to a number of similar sites -- many of them hosted overseas -- which are widely agreed to be not-as-good. These sites have smaller user numbers, which makes it difficult to connect with clients. Also, many sites charge a fee; Backpage was free. I know I have a lot of economically-inclined readers, so I’ll put it this way: The demise of an agreed-upon marketplace for buyers and sellers led to reduced demand, which drove down marginal revenue. At the same time, sellers experienced an increase in fixed costs. Basically, this happened:

And I know you’re probably thinking: “1) These are the short term curves -- in the long run, price will reach a new equilibrium point”; and “2) I’m not sure that the marginal cost curve for blowjobs would be parabolic.” These are solid points; come see me in the comments.

The loss of online marketplaces for sex has also made sex work more dangerous. One of the main benefits of an online system for sex work is that it allowed women to work for themselves; that is, they didn’t need pimps. The absence of a widely-used forum has forced some women back onto the streets -- where violence is more likely -- and made it more difficult for sex workers to share information about dangerous clients. It’s also become harder for sex workers to screen clients and agree on the parameters of an encounter before they meet. Danielle Blunt, a professional sex worker, put it this way:

“When people are negotiating on the streets, you want to get your encounter with a client going as soon as possible, because you’re being heavily surveilled and policed on the streets. So by having the barrier of interacting with someone over email, I can sort of test how they’re interacting with me. It just gives you more space to make a decision before getting in a car.”

Yeah: You know that Pretty Woman “no kissing on the mouth” rule? You need to establish that before the encounter happens. Really, I don’t want to tell Julia Roberts how to do her job -- I hate to be a back seat high-end call girl -- but she should not have sprung that on Richard Gere mid-session. Also -- and again, I’m sorry to be a Monday morning prostitute, but I have to say this -- your one rule is “no kissing on the mouth”? And not, like…I dunno…something involving the rectum? I guess I need to respect her choice; I’m just saying I would have played that hand very differently.

It seems fairly clear that FOSTA has been bad for consensual sex work. But what effect has it had on nonconsensual sex work? The answer is: It’s hard to say. Reliable data about sex trafficking is hard to come by.5 Also, suppose we saw a decrease in sex trafficking convictions -- would that indicate success, because perhaps the demise of Backpage dried up the market for sex trafficking? Or would that indicate failure, because we’ve lost a tool that helped us catch pimps and traffickers?

A new report from the Government Accountability Office -- easily the sexiest federal agency -- suggests that the “FOSTA will help us catch the bad guys” argument is garbage. The report, which came out in June, finds that federal prosecutors have used the new law exactly once. It also finds that the altered landscape has made it harder to prosecute sex traffickers, writing:

“The current landscape of the online commercial sex market heightens already-existing challenges law enforcement face in gathering tips and evidence. Specifically, gathering tips and evidence to investigate and prosecute those who control or use online platforms has become more difficult due to the relocation of platforms overseas; platforms’ use of complex payment systems; and the increased use of social media, dating, hookup, and messaging/communication platforms.”

I told you things were going to get steamy!

This outcome is basically what opponents of the bill predicted. Still, while I’m worried that it might be more difficult to catch bad guys (one police officer described Backpage as “a trap for human traffickers and pimps”), the lack of prosecutions bothers me less. After all: The goal wasn’t to have people set up human trafficking web sites and then have the feds catch them in the act. The goal was to keep the sites off the web altogether. And, if we’re talking about American sites, FOSTA did that. It could be that FOSTA reduced sex trafficking by making selling sex more difficult and less profitable (see graph above).

Or, not. We don’t know. We need data -- Congress should study FOSTA’s effects. Now, 99 times out of 100, when someone says “Congress should study this issue,” that means “I’d like this issue to remain on the back burner until I eventually die.” But this is the exception to the rule: Congress actually should study FOSTA so that we can weigh the clearly-negative effects on consensual sex workers against the largely-unknown effects on nonconsensual sex workers.

In the last Congress, Elizabeth Warren and Ro Khanna authored bills to study FOSTA. The bills died in committee; it was that ignominious demise where a bill’s Congress.gov profile just sort of…ends. There are kindergarten-class goldfish who die more heralded deaths. Still, attitudes about sex work are changing quickly, so maybe the bills have a shot in this Congress.

Consensual sex workers were shut out of the process that led to FOSTA. They were erased by I Am Jane Doe and ignored by the Senate. It should come as no surprise that they’ve been harmed by a bill written by a Congress that continued the shameful tradition of simply pretending that sex workers don’t exist. They do exist; sex work has been around for all 200-odd millennia of the human species, and you’re not going to end it by taking a web site that’s basically CarFax for Hand Jobs off the internet. It may be the case that the damage done to consensual sex workers is outweighed by a decrease in sex trafficking; we just don’t know. Congress should at least bother to find out.

The vote was 97-2 in the Senate and 388–25 in the House.

You sometimes hear this bill referred to as “SESTA-FOSTA”. “SESTA” is the “Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act”, which is just the Senate version of FOSTA. SESTA was incorporated into FOSTA, so for brevity, I’m calling the package that Congress ultimately approved and that President Trump signed “FOSTA”.

The “effectively” hides a bit of nuance here: Both Backpage and Craigslist Personals were removed shortly before FOSTA was signed into law. But, in both cases, it seems to have been a “reading the handwriting on the wall” situation. Craigslist Personals shut down after Congress passed FOSTA but before Trump’s signature (which was certain). Backpage shut down their “adult services” section the day before a Senate hearing, and the entire site was shut down by federal authorities less than a week before Trump signed the bill into law. Though FOSTA technically post-dated the demise of both sites, it seems true that both were shut down as a direct result of Congress’ actions.

I’ve got some methodological issues with this survey, mainly that an online survey will disproportionately reach a certain type of sex worker (i.e., a tech-savvy one). So, I would take the survey’s findings with a grain of salt. But I have no reason to doubt the quotes’ authenticity.

I looked -- if there’s a widely-trusted source for sex trafficking data, I wasn’t able to find it. Many data sources, like the State Department’s annual Trafficking In Persons Report, cover all forms of trafficking, not just sex trafficking. Also, many address trafficking globally, not just in the US. I also found several fact-checks about debunked human trafficking statistics, which made me wary of using any source I didn’t already know.

This subject makes me feel weird because I have difficulty being okay with sex work in general. (I’m not a Puritan! I just dress like one. What can I say, I enjoy a good shoe buckle and wide brimmed bonnet).

I guess I accept consensual sex workers at their word, but it’s simply not the same type of physical work as other jobs. There’s a fundamental difference and exploitative possibility between spreading mulch or mowing lawns or laying bricks and inviting a stranger into your actual body for money. (Although in this context all three things I listed first sound like something someone would ask a sex worker to do on Craigslist.)

The validity of sex work is obviously not the point of your post. Ugh, fine. So I guess all this is to say, yeah. Someone should look into this.

Jeff, what's steamy is your mind and your craft. You could write about corruption in the reupholstery industry, and I'd get hot.