What Building a Media Thing Looks Like When You're Doing It

I'm counting this newsletter as "a media thing"

What is Fox News? What I mean is: If we were to describe the original sin that makes Fox News a hot condom full of dinosaur shit, what would that sin be? I think it has to be a near-total lack of journalistic ethics. Fox News isn’t news, it’s entertainment. They’re not bound by any standards of objectivity or truth; they just give their audience what they want, and their audience wants narratives about how Democrats are the root of all evil, preferably delivered by a blonde woman with a very lady-who-self-publishes-books-about-how-to-be-a-winner vibe.

Everyone is broadly aware of media bias. When I was a media consumer with a non-media job, I knew bias existed but didn’t think about it much. I knew that the Times and the Post were written by pointy-headed liberals like myself, the type of person who buys physical books so that their apartment will feel literary. Cable news was trashier, prone to sensationalism because they have to put on a show every single night and can’t say “not much happenin’ today -- here’s a Punky Brewster rerun.” Other outlets had other biases: 60 Minutes liked to help geezers feel morally superior to anyone born after the advent of pasteurized milk, bloggers turned their antisocial tendencies into a superpower by picking fights to get attention, and local TV news seemed to be a city-wide effort to emasculate the weather guy. I was generally aware of the pressures people in media faced but assumed they were mostly background noise.

Then I got a job in media, and let me tell you: The pressures are WAY more intense than I thought! And they’re also different from what I assumed. I faced one set of incentives when I wrote for a news-y TV show, and now I’ve moved to Substack -- the plucky garage band of the media world -- and the incentives have shifted again. Those incentives are what they are; I can’t change them, nor can I swear to be a pillar of virtue standing motionless amidst the winds of temptation (in fact, I can just about promise to be the opposite of that). But I can write about the incentives so that people who don’t work in media might have a clearer sense of how what they’re reading and watching got so bad.

Media in a large organization: Everyone in the world is your boss

Many people have noted that large media companies seem to be becoming monocultures. In my experience, this seems to be true, and I’m honestly surprised that they aren’t bigger monocultures than they are.

Imagine you’re a young person who just got hired by a large media company. You’re pumped: Your days of making $200/month as a freelancer are over. You seem set to prove to your parents that it was smart to major in journalism, even though they tried to push you towards something more practical, like History of Finnish Puppet-Making or Balloon Animals.

Are you going to go against the grain, hold firmly to your journalistic principles, and maybe push the publication in a new direction? Hell no: You’re going to dedicate yourself to churning out the crap that made the place successful enough to hire you at $30K a year + fridge leftovers. If you work at, say, a site that makes those click-bait “Ten Olympic Athletes Who Had a Boob Fall Out During Competition” articles, you’re not going to walk into a meeting and pitch an article about how EU reforms are altering the lumber market. People will think you’re weird, and your boss will regret hiring you instead of just training a border collie to do your job. You’re going to pitch boobs, boobs, and more boobs, plus the occasional think-piece about former child stars who got fat. For credibility.

Organizations are comprised of people, and people are social. They feel pressure to conform, and that’s especially true of young people. As market forces have made newsrooms increasingly dependent on low-cost, low-experience workers, it stands to reason that a publication’s habits and biases might self-replicate. A grizzled old news veteran might have strong opinions about what “news” is and what the publication should be; young people cost less and usually just pitch whatever they think will run. You can get a few good years out of them before they publicly call you a racist and force you out of the business.

The conformist pressures within an organization can push it to become what it already was, only more so. But what about the people at the top? They’re the ones calling the shots -- they’re largely free from those pressures, right? Of course not. For starters, all indications are that top-level people at organizations everywhere are terrified of the easily-offended, cancellation-happy Army of Twerps they’ve hired. It’s basically that Twilight Zone episode where everyone fears the mind-reading little boy with evil powers, and I’m not sure this sentence even needs the word “basically”. It’s pretty close to literally that situation.

But the bigger problem comes from the fact that most publications are in a somewhat-abusive relationship with their audience. In the modern media environment, you either give your audience what they want, or they abandon you. That was less true a generation ago; back then, a lot of people got their news from monopolistic local newspapers. There was one cable news station and three nightly broadcasts, and they were all pretty similar. The internet was something nerds at MIT and Caltech used to exchange baseball statistics. Twitter was but a gleam in Satan’s eye. I’m not lionizing this model -- it had plenty of downsides -- but news outlets were more able to say “Here’s the news, and if you don’t like it, tough shit.” And for the most part, the audience would stick around.

I’m far from the first person to point out that the proliferation of media options and an increasing reliance on subscriber-based business models has changed news. But I want to add my voice to those expressing just how intensely those pressures are felt. Last Week Tonight was, in many ways, the most insulated-from-those-pressures environment one could be in. For starters, we were a comedy show, so if we botched the news part, we could maybe survive as long as the jokes were good. Also, we were on HBO, which (especially back then) took a very hippie-parent-coaching-a-soccer team approach to ratings: It wasn’t about the numbers, it was about expressing yourself and having fun! I’ll give John a good amount of credit for frequently resisting pressure to just go after ratings, especially in the Trump era. But there were lines we chose not to cross; there were narratives we shied away from because they were deemed too challenging to our audience. There were also some narratives our audience loved, so we gave them those stories over and over.1 I’m sure other outlets feel those pressures -- how could they not? Your audience pays your bills, and you defy their expectations at your peril.

Independent media: A landscape of absolute freedom and terror

Substack is a world of pure journalistic freedom. Gone are the gatekeepers and corporate sponsors, the office politics, the pressure to conform, and the bare-knuckle careerism. Also gone: Fact-checkers, quality controls, and anyone who might tell you that the world doesn’t need a 5,000-word column about how The Snorks predicted the Me Too movement.

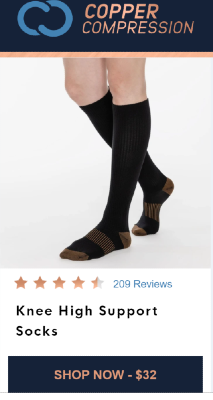

And here’s what’s still present: The patronage relationship between a writer and their audience. Let me be honest: I will do anything you fuckers want me to do. Want me to turn this newsletter into a Hollywood gossip blog with alt-right sympathies? Consider it done. How ‘bout a Marxist take on tennis? No problem. What about a parenting blog that just validates every choice you’re already making, or a collection of cat videos with anti-woke captions, or some “lifestyle and wellness” bullshit that’s just a long-con to sell Copper Fit socks? This newsletter could be any and all of those things.

I’m joking (unless there are takers on that Copper Fit socks idea). But the reality is: Without an audience, this thing dies. The pressures I felt to write stuff that clicked with the audience when I worked at a TV show are multiplied by ten now that I’m out on my own. When you’re part of TV show, the organization is big enough and has enough momentum that it can tolerate a small amount of boundary-pushing. You can try something, and maybe it won’t work but people will still like the show on the balance, and an individual within the organization might be able to carve out a niche as a source of mild apostasy who’s never quite worth firing. Basically: The organization is big enough that it can swallow a small dose of poison and survive.

But that same dose of poison could kill a newsletter. To be clear: The “poison” in this metaphor is anything the audience doesn’t like. It’s in the writer’s interest to avoid that stuff, and it’s also in their interest to lean heavily towards things their audience does like. Jesse Singal wrote about this topic recently, saying:

“…it’s undeniably the case that I benefit the most, financially speaking, from writing about fevered culture-war controversies. Posts about youth gender dysphoria or the broader debate over trans rights, for example, almost always bring me a slew of new subscribers, as do essays about the wokeness wars.”

I will second that opinion: There’s gold in them thar culture wars! It’s an incredibly-easy variable to tease out: The link between culture war relevance and virality is as easy to establish as the link between wearing a high school gym uniform and body shame.

You’re not going to build an audience by being a wallflower -- you need to get on Twitter and stir up some shit. Call it the Milo Yiannopoulos model: If you’re getting attention, even if it’s attention for being a character so egregiously awful you belong in a Cormac McCarthy novel, that’s a form of success. Part of me thinks I should get on Twitter and just start torching anyone with more than 500,000 followers; my career would really take off if I could get Sacha Baron Cohen to dunk on something ignorant that I said, or if I could get Steven Pinker to call me an asshole. At an absolute minimum, people would see my name, and anyone who doesn’t like those people would take my side.

In a nutshell: It’s all about building an audience and then keeping that audience. You won't build an audience by being boring, and you won't keep your audience by telling people things they don't want to hear.

Which sort of makes Fox News the ideal news outlet for our time. They succeed because they don't give a fraction of a fuck; they will put anything on TV if it will get people to watch. They have an audience, and they portray a world that perfectly reflects that audience’s beliefs, which keeps people coming back.

It seems to me that the only brake against that cycle is some sense of what you “should” be producing. I put “should” in quotes because what does “should” mean in this context? “Should” according to who, and why? The funny thing is: I don’t think it really matters. As long as you establish some “should” as a magnetic north exerting some pull against the constant pressure to just tell people what they want to hear, you’re likely to avoid tumbling into a cycle in which all objectivity is lost. Of course, your “should” might be completely terrible; the publishers of The Daily Stormer might find themselves thinking “this article isn’t extremely racist -- is it what we should be doing?” So, awful, for sure. But the publishers of The Daily Stormer can’t be accused of being sellouts.

I don’t totally know what this newsletter is yet. When I started, I wrote a Citizen Kane-style Declaration of Principles because I thought it would be funny to steal that move from a film about a guy who loses his principles. But I actually did put some principles in there. Have I stuck to them so far? I don’t know. Will I stick to them? Doesn’t sound like something I’d do, but you can’t rule it out. At any rate, I want you to know that I’m thinking about these things. These are the waters I’m navigating, and I’ll do my best, and we’ll see how it goes.

Unrelated: Have you seen these things? They look awesome!

***Poll for next week***

I'd like the next column to be about...

1. The child-pornography-scanning software that Apple has decided to use but that other companies are rejecting [VOTE FOR THIS]

2. How we need to stop trying to make policy via choke point, like people do when they try to to pressure credit card companies into cutting businesses off or try to deny gay marriage licenses by having the county clerk refuse to give them out [VOTE FOR THIS]

3. Something from the news. There's a lot going on -- the Texas abortion law, the storm in the Northeast, Afghanistan...come on, Maurer, read up and develop a take. [VOTE FOR THIS]

There’s an interesting caveat here: I actually think there’s reason to believe we might have misread our audience. I probably should have said “we gave the audience narratives that we thought they loved.” I actually think if we had gone a different route around 2017/18, we might have done just fine with different narratives. But we did what we did, and the audience evolved as the show evolved.

In a big, diverse world, there is an audience for almost anything -- the trick is reaching and retaining them. So it's true that people are beholden to their subscribers, but those subscribers aren't a random sample of the population -- there's a reason they came here in the first place.

Some perspectives and styles are more marketable than others. But I think it's best to start out writing what you like, because you're going to be stuck with it as the audience grows. Any change in direction results in complaints like "ugh this used to be good" -- because every writer's audience is disproportionately composed of people who liked their previous work.

Hey Mr. Maurer,

I have a question about the genesis of your comedic style, if you don't mind the bother. I was an avid follower of LWT during its (I suppose, grudgingly) "golden era" - roughly 2017-18. My love affair with the show ended around the same time my love affair with Minecraft ended, and for roughly the same reason: despite the local variations, it seemed like there was nothing original left in either of them. It was getting to the point where some 90% of the jokes were predictably over-the-top similes, in this kind of vein: "Commenting on newsletters? The only time you should address an ex-comedy-writer is when you need him to stop taking up a whole row of seats in the subway. It's 6:30 in the morning and people are beginning to squish in like the phlegm-filled bottles in Michael Phelps' living room -- You need to move!" ... and so on and so forth.

Anyway, I assumed that this style of humor (add scare quotes liberally, as appropriate) was the result of some kind of democratic process in a fairly large committee; I guessed that it would be the lowest common denominator that everyone would be able to agree on. But now, while reading -- and enjoying! -- your newsletter, I've noticed that a lot of the same distinctive comedic quirks and repetitions that I remarked on so often in LWT are present in your independent writing. Was this your style prior to LWT? Did you singlehandedly help set the tone in the newsroom? Or did they form you -- did you become familiar with the winning strategy of the show? Were there just (shudder) a bunch of you, all coming up with roughly the same idea of comedy? Something in NYC's lovely unfiltered water, piped into those 57th street offices? Please help me to understand, and thank you again for the lovely newsletter.