To every 17 year-old who saw the chaos in and around Kenosha, Wisconsin last August and thought “Time to go to the basement and rub one out”: I salute you. Every high school student who responded to the unrest with uneventful nights of Futurama reruns, Flamin’ Hot Cheetos, and rhesus monkey-level onanism did God’s work. The world needs more young exemplars like those directionless clumps of cell matter.

From the moment Kyle Rittenhouse showed up in Kenosha with an AR-15, only bad things were going to happen. There is literally no problem to which the solution is a 17 year-old with an AR-15; if I was in a zombie apocalypse, I’d probably feel safer around the zombies than around the child with a deadly weapon. The courts are now trying to determine culpability for what happened that night, but it’s too late to prevent the horror: Two men are dead, another is maimed, and obviously it would have been better if nobody had been there to begin with.1

One tragedy in this galaxy of tragedies is that Rittenhouse seemed to have imagined himself some sort of do-gooder. He carried a first aid kit and yelled “I am an E.M.T.!” (He wasn’t.) “If you are injured, come to me!” he shouted. His social media accounts showed an interest in police and the military, and he dressed in quasi-military clothes from 5.11 Tactical Gear and Ariat. Shortly before his involvement turned deadly, he used the language of first-responders, saying: “If there’s somebody hurt, I’m running into harm’s way!”

This is a little boy playing war. He’s a high-visibility example of what can go wrong when a burning desire for purpose mixes with the deep stupidity of youth. Relentlessly-negative media narratives disguise the fact that in the past several decades, our society has become less violent, less bigoted, and more prosperous. At the same time, war — especially war other than civil war — is going extinct. The peace and prosperity that previous generations fought for has largely arrived. But it might have produced a generation of bored young people who are starved for purpose and inventing dragons to slay.

One of lies we tell kids is: “You can be anything you want!” That sentence really throws the word “can” around recklessly; they can be anything they want the same way that Charles Dance can be the spokesperson for Bratz dolls. It’s true that there’s no physical law of the universe preventing it.

It would be cruel to look a five year-old in the eyes and say: “The chances of you being exceptional or notable in any way are incredibly small. The odds of you even having a Wikipedia page are one one-millionth of the odds of you being eaten by a house pet after you die.” A young person needs to believe that they’re destined for greatness. The moment that a person realizes that they won’t achieve fame and fortune needs to be the same moment that they think: “Fine, fuck it, I’m tired anyway and mostly just want to sit down.”

Much of childhood is spent engaged in fantasy role-play. Most movies for young people are about a hero overcoming obstacles as part of an amazing journey. Video games involve projecting yourself into an avatar, and that avatar typically gains skills and does something incredible, like win the Super Bowl, slay dragons, or survive the apocalypse. This appeals to a young person’s egoism and desire for control, which is important because — though we tend to downplay this fact — children are extreme narcissists with a Genghis Khan-like thirst for power.

Of course, a young person’s desire for power (within reason) isn’t a bad thing. When you’re young, the world is a scary place, and you want to believe that you’ll acquire the skills you’ll need to master it by the time you grow up. When you hit adolescence, the angst you feel about making the jump to adulthood gets combined with the competition and social climbing that comes with attracting a mate; that makes everything more intense. Every cell in a teenager’s body is pushing them to do something, to be something…unfortunately, they don’t know how to achieve that. The fact that we reach sexual maturity a whole decade before cerebral maturity has to be the funniest, darkest joke in all of human history.

Young people look to heroes as models of who they can be. For many boys, that hero will be a soldier, i.e. someone who has passed the test of manhood. I mentioned video games a minute ago — here’s a World War II soldier from a recent Call of Duty game:

I hope it’s not weird to say this, but: That’s an extremely fuckable digital rendering of a person who, if real, would be dead by now. You can see why a teenage boy would want to pretend to be that person. It sucks to be an ordinary kid in an ordinary town with ordinary prospects, but it absolutely fucking rules to be Sergeant Chunk Thickslab, Nazi Hunter.

Soldiers — especially World War II soldiers — receive reverence sometimes bordering on deification. Of course, they are heroes.2 They put their lives on the line, which is something that I, for one, don’t know if I could do. My granddad — a veteran of the Pacific theater — once told me that he fought so that I wouldn’t have to, which is the thought that makes me feel least-guilty about never having served. In a way, my cushy, soft-handed existence is what my grandpa was fighting for. So — logically — the more pampered and frivolous I get, the more successful he was. And, though he’s passed now, I like to think that he’s in a place where, somehow, he knows that I threw away a muffin this morning because it didn’t have enough blueberries in it. That was for you, Grandpa!

Appreciation for people who fight is warranted. But past a certain point, hero worship is unhealthy. It’s clear that many people — especially young people — want to be part of a generation-defining epic struggle. World War II was an epic struggle and remains a subject of fascination three-quarters of a century later. The Cold War was another major world event, and though it didn’t produce any great battles, it did produce a James Bond franchise that made the fight against the Soviets seem awfully bad-ass. After all: If an endlessly suave fuck machine who drinks on the job and has a license to kill isn’t the ultimate aspirational figure for a powerless teenage boy, then I don’t know what is.

The end of the Cold War left us with no obvious existential threat. This is a problem for anyone searching for a purpose; a person in that situation is likely to inflate the best-available threat to existential status in order to give their life meaning. And, sure enough, that basically happened; it’s clear in hindsight that many people went a tad insane exaggerating the threat posed by terrorism after 9/11. Al Qaeda — though heinous — was puffed up to fill the existential threat vacuum despite lacking some things the Soviets had, such as a hockey team that we could beat at the Olympics. But hey: No terrorist organization is perfect.

Terrorism was and is a real threat. But — even after 9/11 — it has never been an existential threat. It’s a serious problem that needs to be dealt with, but it’s not something that should make us lose our principles or change everything about how we live. Nonetheless, a crusading mentality gripped many people in the 2000s, and some of that was clearly related to the desire to have a greater purpose. To a large extent, the impulse to be a stalwart defender of the good was admirable. But in many cases, it bubbled over into zealotry, and the desire to be involved in a generational struggle caused some people to make bad decisions.

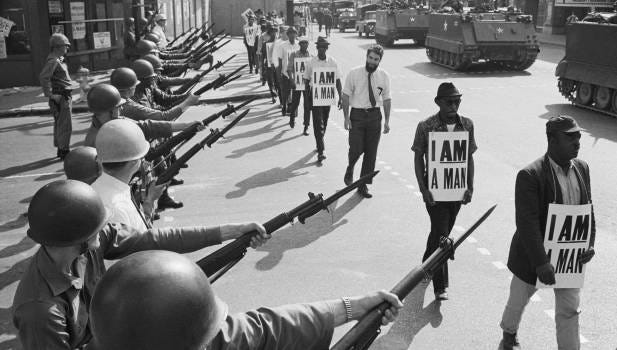

Like World War II soldiers, the civil rights protesters of the ‘50s and ‘60s were legitimate heroes. They were, in many ways, soldiers for the bookish set: They marched, they faced danger, but they did it without all that back-breaking gear. In much the same way that an image of a hardscrabble World War II grunt invokes a visceral sense of respect, so, too, do images of civil rights protesters maintaining dignity in the face of imminent violence.

One thing I find interesting about that photo is the dorky white guy. Though the civil rights movement was led by and largely composed of Black people, there was always a dorky white guy (and girl) contingent. White people know this; we know about the Freedom Riders and the Quakers. The fact that there were white people involved makes the movement more accessible to us; it might feel a little cultural appropriation-y to project ourselves into Medgar Evers or Martin Luther King, but we can always imagine ourselves to be the beardy white dork (above) with the highwater pants and an actual, real-life pocket protector.

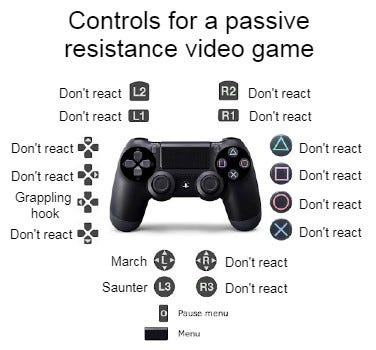

Civil rights protesters play the same role in the psychology of some left-leaning people that World War II soldiers do in the psychology of some right-leaning people: They’re aspirational figures. And, as with the soldiers, that’s because they undeniably were heroes. Both World War II soldiers and civil rights protesters fought for a cause that was undeniably righteous, bravely faced danger, and won. Really, one of the primary differences between the two groups is that the civil rights protesters’ passive resistance doesn’t lend itself well to a video game.

I’m not the first person to think that some overzealousness on the left might stem from a desire to recreate the civil rights movement. Here’s Andrew Sullivan talking to Tyler Cowen (at 51:26):

“Because the elites kind of have a Martin Luther King Jr. envy. Every generation wants to have that moral quality, that sense that they are shifting the arc of history in a better way, even though we’ve generally done about as much as we possibly can to do that in terms of — within the possibilities of — a liberal system. There’s that. The need to feel worthy and the need to feel that you’re doing things.”

I think it’s undeniable that this exists sometimes.3 I feel it in myself; I admire what civil rights protesters did and — on some level — wish that people saw me with that kind of reverence. That’s narcissistic and fucked up, but there you have it. Of course, as with all my negative impulses — and what is my psychology if not a 20-ring circus of negative impulses? — I try to be aware of my tendencies and keep things in check. The world, after all, is not some off-Broadway theatre in which I stage a self-produced show called Jeff: Heroic Bestower of Justice Upon the World.

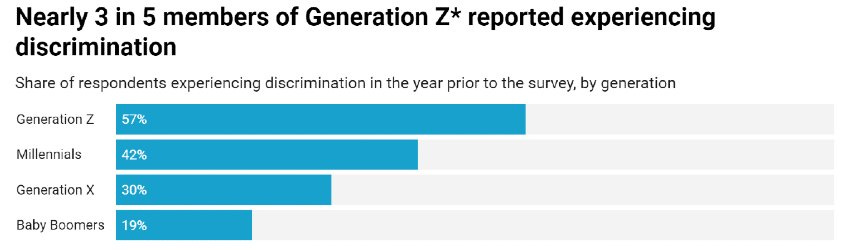

The desire to be part of a great racial justice movement can cause people to inflate the very real problem of racism. One of the most annoying ticks of the left is to pretend that present-day America is largely indistinguishable from 1950s Alabama. And, as racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia become less common, people work harder to find them. Just this week, there was a stunning finding from the Center of American Progress that LGBTQIA+ members of Generation Z report more discrimination than their older counterparts:

Obviously, there is no way in a million hells that young LGBTQIA+ people — who, we can assume, disproportionately interact with people their own age — actually face nearly three times as much discrimination as baby boomers. If you think that Generation Z is several times more homophobic and transphobic than the baby boomers, may I humbly recommend that you donate your brain to science, or better yet a cannibal, because you are not using it. What’s clearly driving these numbers is that Generation Z is reporting higher levels of discrimination. Just as some on the right exaggerate the very-real threat of terrorism, some on the left exaggerate the very-real threat of discrimination, because the struggle against that threat can be self-defining.

The extreme right and left-wing versions of the crusader mentality perpetuate each other. Charlottesville and Trump helped cultivate an unyielding anti-fascist contingent on the left, who sewed much of the chaos last summer. That, in turn, was viewed as intolerable by militant types on the right, who leapt into action. That action was used by some on the left to justify violent counter-tactics, and so on and so on. By late summer, we were seeing small-scale clashes with no real connection to the post-George Floyd protests between “right” and “left” groups that were really just rival fight clubs. Past a certain point, the defining characteristic of violent protesters tends not to be any political ideology, but rather a desire to be in it. They want to be involved in something extreme and exciting.

I don’t mean for this essay to be a call to inaction. When I shake my fist at overzealous crusaders and salute inert blobs of listless meat, I’m joking. I still think it’s good to be politically engaged — those are the people who drive positive change. But I do think that if a person is naive, impulsive, and motivated mostly by a sense of self-aggrandizement, it would be better if they sat things out.

It’s fairly well-documented that social media contributes to tribalism and polarization. It might be worth thinking about why that’s true. I think a big part of it might be boredom — we’re all bored out of our minds, waiting for someone we dislike to say something stupid so that the dunk-fest can begin. By exaggerating perceived threats, we create civilization-threatening bogeymen that need to be defeated at all costs. Crusading against these bogeymen can provide the thing many of us are missing most: A sense of purpose.

If my grandpa’s end-game really was to allow me to live the life of a pampered little fancy lad, I think he succeeded. I’ve had a package downstairs for four days because I don’t want to put on pants to go get it, and that — if you think about it — is really what the Battle of Okinawa was all about. But a byproduct of this hard-earned apathy — which so many of us enjoy — might be an increase in overzealous crusaders. And when confronted with that personality type, I’d prefer a languid pile of DNA strands every time.

Some might interpret this sentence as me inferring that people shouldn’t have protested the shooting of Jacob Blake. I’m not saying that; peaceful protests are always legitimate, and if they’re met with violence, then the fault lies entirely with whoever’s doing the violence. But to describe what was happening in that part of Kenosha that night as “people protesting the shooting of Jacob Blake” doesn’t seem accurate; it seems pretty clear that it was groups of people milling around in a lawless environment looking to stir up some shit. And I feel comfortable saying that they should have just gone home and not done that.

Obviously, most but not all soldiers are heroes. The ones who do bad things are not.

For what it’s worth, I don’t agree with the middle part of what Sullivan says, that we’ve “generally done about as much as we possibly can to [shift the arc of history] in terms of — within the possibilities of — a liberal system.” But I agree with what he says before and after that, about elites having MLK envy and wanting to have the sense that they’re doing great things.

Ever since that LGBTQ survey came out, my wife and I (lesbians) have been doing bits about the oppression of Gen Z queers.

“Ugh, I just got microaggressed at Target. I mean, the cashier didn’t say anything, but I could tell he wasn’t validating my demisexuality.”

“God, that’s awful. It reminds me of when all my friends died of AIDS.”

Tasteless jokes aside, the responses to some of the other questions are disturbing. A significant % of Gen Z queers say they avoid stores, restaurants, and the doctor for fear of discrimination. It’s not healthy. For every 20yo queer person who feels empowered by their TikTok diary of oppression, there are a bunch of kids watching who think “Oh my God, the world wants to murder me.”

"One of the most annoying ticks of the left is to pretend that present-day America is largely indistinguishable from 1950s Alabama."

I will never understand this sentiment, as long as I live. It is absurd. I was alive in the 60's and 70's. I remember the 60's and 70's.

In the 50's, Bayard Rustin was screamed at, insulted, assaulted, arrested, and served time on a chain gang for his activism.

Fast forward to 2021: "That damn well-meaning but clueless white woman complemented my hairstyle. What a racist."