The “You Can Only Write Characters Who Are Exactly You” Idea Is Not Workable

It’s Actually Pretty Racist and Dumb

Let me start by admitting my biases: I’m a writer, and, like most writers, I’ve written things that didn’t go anywhere. The one that hurts most is my still-unpublished novel about a Black girl growing up in Stamps, Arkansas during the Great Depression. It’s a coming-of-age story about racism and sexual abuse, and was shunned by the literary world just because the plot is identical to Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. “Could you maybe change the location from Stamps, Arkansas to Buckner, Arkansas?” my agent asked. “Or at least name the main character something other than ‘Maya Angelou’?” I told him to go to hell and then got a new agent -- nobody tells me how to write!

The religious left is putting their stamp on TV, movies, and books. Legitimate concerns about lazy writers producing stereotypical characters have morphed into a race-essentialist viewpoint that’s wildly out of control. I’m fairly certain that classics like The Wire, Schindler’s List, and The Remains of the Day -- to name three examples I’ll talk more about later -- couldn’t get made today. Which is a big problem, unless you’re a person who saw Boss Baby 2 and thought: “This is humankind’s crowning artistic achievement.”

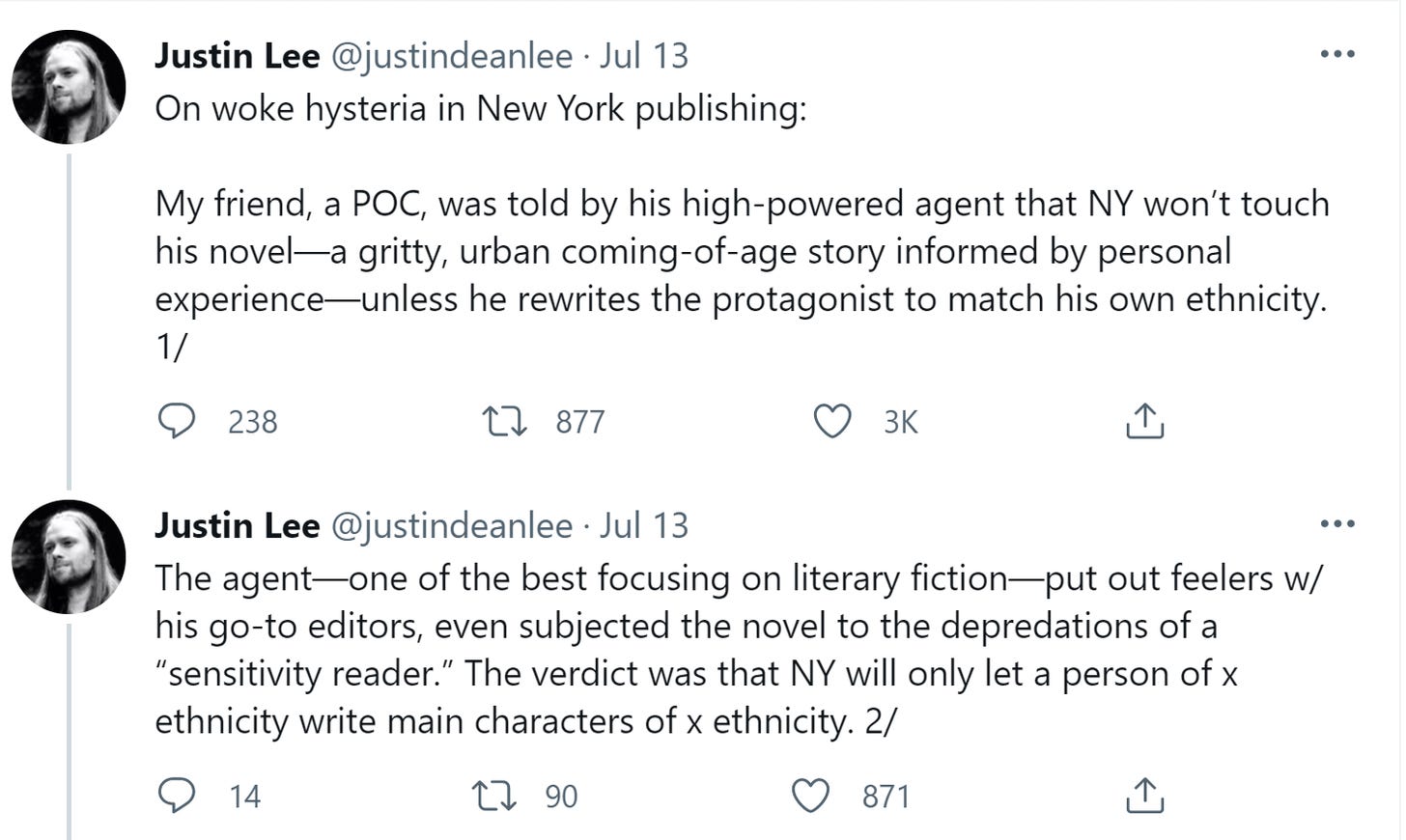

An example of the thinking that’s causing all the problems can be found in this recent Twitter thread:

I have no idea if this story is true; for all I know, the book was rejected because it’s a big, frothy bucket of horse excrement. But we know that stories like it are true. American Dirt author Jeanine Cummins became the subject of a Category 5 Twitter storm for telling a story about Mexican immigrants that was “not hers”. Jesse Singal wrote a series of articles chronicling the race-essentialism that has taken over young adult literature. Those stories match my own experiences in television, where ideas about who can write what have taken root seemingly without anyone asking: “Is this progressive, or is this an attitude towards race that would be at home in a book from the 1800s called The Traits of the Peoples of the Seven Continents?”

The current madness is a perversion of a legitimate critique. There is, without a doubt, something I’ll call the “hippies on Dragnet” problem. Dragnet, the ‘60s cop show that served as a cathartic release for squares whose greatest wish was to see some filthy long-hairs face justice, made no attempt whatsoever to understand the counterculture or portray it accurately. Hippies on the show are never anything more than hairy loudmouths dressed like a mashup of Pocahontas and Huck Finn, and whose only character traits are: 1) They say “groovy” a lot, and 2) They get their asses busted by Joe Friday. The writers clearly never bothered to meet any actual hippies. Not that that would have been easy; if a guy who looked like Vince Lombardi had shown up at a Country Joe and the Fish concert and said “Hello, fellow freaks! Care to rap with me?” I suspect it wouldn’t have gone over well.

When applied to hippies, lazy writing leads to lousy characters. When applied to an ethic group (or other group), it leads to ugly stereotypes. Was there a single gay, male character on TV before Will & Grace who wasn’t a lispy, effeminate guy in cutoffs? When did the first Asian character without any ancient wisdom to impart make it to the screen? The shallowness that leads to these stereotypes comes from assuming that you know something about a person based on their ascriptive traits.

Some critics, to their credit, continue to focus on the writing, not the writer. The New York Times review of American Dirt criticized Cummins’ characters without declaring her incapable of writing them because she’s not Mexican.1 But it’s common for people to adopt the simple heuristic that any major character should share the author’s traits. This is the logic behind the “Own Voices” movement, which promotes books by “an author from a marginalized or under-represented group writing about their own experiences/from their own perspective, rather than someone from an outside perspective writing as a character from an underrepresented group.” That definition comes from the Seattle Public Library, which also includes this warning on its web page:

Not good enough, Seattle Public Library! If you’re really serious about steering people towards diversity, you’ll start slapping big, red labels on books that say: “WARNING: MAY CONTAIN WHITE PEOPLE!!!”

I’m all for hearing stories we haven’t heard before, and I’m all for expanding access to fields that are difficult to enter. But I don’t think an ethic that insists that authors only write from “their own” perspective is remotely workable. The first problem is that there are already too many bratty, self-indulgent works out there about a writer’s boring life. A lot of indie movies fit this mold; they contain conflicts like: “guy’s father is a tad distant” or “girl doesn’t immediately meet man of her dreams/have astonishing success in her career.” An over-application of the “write what you know” ethic can trick a writer into thinking that their upper middle-class 20-something life is interesting. Which -- let me be perfectly clear about this -- it is not.

Many authentic, important works have been authored by people not writing about “their own” group. The book that became the movie Schindler’s List was written by Thomas Keneally, an Australian Catholic. Keneally did his research, interviewing numerous Schindler Jews, which is why there’s no scene in the book where one Jewish character turns to another and says: “Thank Christ it’s finally Saturday -- let’s make pork chops!” Another classic by an “outsider” is The Wire, whose no-filter realism distinguished it from other cop shows (like Dragnet). The Wire is the brainchild of David Simon, who is not a cop, nor is he Black, nor is he -- to my knowledge -- a drug dealer. One could argue that the story wasn’t “his” by any measure. But Simon worked the City Desk at the Baltimore Sun for 12 years -- he knew that world inside and out. His deep knowledge base is why he could write The Wire about the drug trade and, for that matter, also The Deuce about the porn industry -- the guy watches A TON of porn!2

If David Simon was shopping The Wire today -- and if he was a nobody and not David Fucking Simon -- he might get it into the hands of a producer who would think “this guy covered crime in Baltimore for 12 years, and these characters seem really authentic -- this can work.” But he’d definitely get it to several producers who would think “White guy writing a show about mostly-Black characters -- so this show is basically Career Suicide: Baltimore. Pass.” There’s an obvious catch-22 here: White writers aren’t supposed to write non-white characters, but they also shouldn’t write something that’s “too white”. My advice to white writers is simple: People like movies where a talking dog and cat try to find their way home. Write one of those.

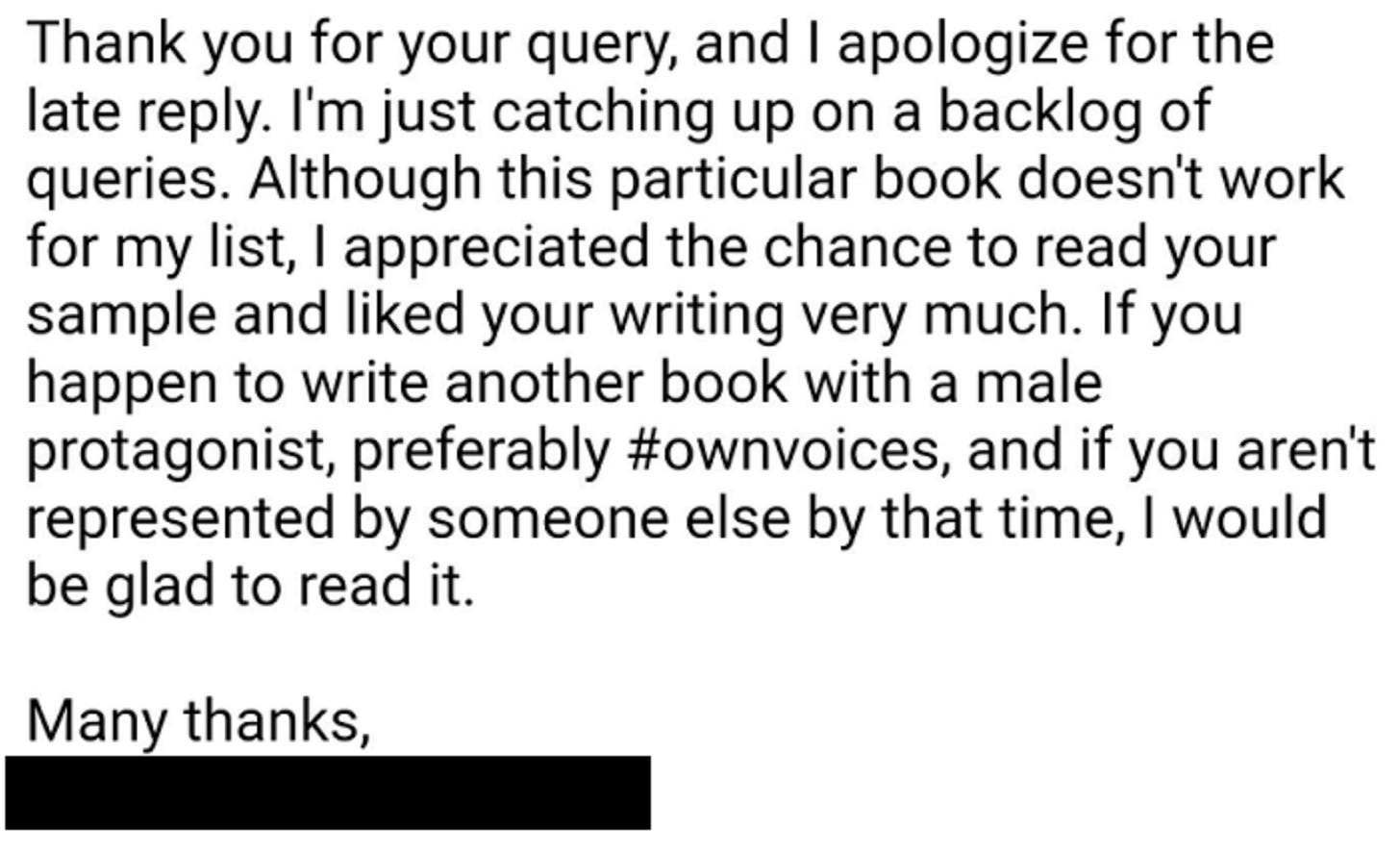

Fixating on a writer’s race is bad for non-white writers, too. Non-white writers are often pigeon-holed based on their race; I know several who are sick of being asked to write about “their experience”. Here’s one reply to a manuscript that a non-white writer received from an agent based on nothing more than his ethnic-sounding name (the writer shared this reply with Jesse Singal):

Translation: “We don’t want this because you’re a non-white male who wrote a white female protagonist, but if you want to write something about your own race and gender, we’d be interested.” This attitude is incredibly reductionist, which I’d argue also makes it racist. Plus, it’s bad for creativity; it treats the writer as just a transcriber of their own experiences. It disallows the possibility that a writer might have something to say that’s not about race or identity (could you imagine?). Ironically, it makes the same mistake that led to the racial caricatures of the past: It assumes that you can know something about a person based on their ascriptive traits.

If this logic had been dominant in the ‘80s, it might have snuffed out the critically-acclaimed book-and-later-movie The Remains of the Day. The Remains of the Day is a period piece about a servant in a large, British manor; it’s basically Downton Abbey before Downton Abbey stopped being a show about the stultifying British class system and started being a show about pretty dresses. The book that became the movie was written by Kazuo Ishiguro, a Japan-born British novelist, and that’s why I think it’s interesting: It’s a work about an exclusively-white world by a non-white writer. How would that book have fared in today’s race-obsessed climate?

Ishiguro’s first two novels had a connection to Japan. However, the first had a female protagonist, and the second took place in a country Ishiguro hadn’t seen since he was a toddler. So, if he was starting his career today, it’s possible that Twitter would have cancelled Ishiguro twice before he put pen to paper on The Remains of the Day. I can also imagine Ishiguro’s agent pushing him to stick with the Japanese-themed stuff; “You’ve got a chance to solidify your brand,” is what the agent would say. But Ishiguro wrote The Remains of the Day, which, in today’s atmosphere, might raise the question: Was the world of a British manor “his”? He grew up in Britain, though not the part of Britain where the book takes place, and his dad was an oceanographer, not a servant...is any of that a problem? Also, is it a problem that the predominantly-male world Ishiguro created was adapted for the screen by a woman, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, a German-born British screenwriter whose early works were about India (she married an Indian man and lived there for 24 years), though she was not, herself, Indian? If you’re scoring at home, I count about a baker’s dozen of cancellations between Ishiguro and Jhabvala before they even get to The Remains of the Day.

I think this is a weird, insulting, racist way to look at writing. The questions in the previous paragraph are the wrong questions. The “who owns what?” game puts strict limits on a writer’s creativity and has no clear logic. It also inevitably devolves into rhetoric that implies that each group has an “essence”, and that people within the group share that essence. A more viable standard is to judge the work based on the work; stop asking “Who wrote this?” and start asking “Is the writing any good?”

It’s possible to write outside your identity while being sensitive to the fact that you’ll need to work to see the world through your character’s eyes. Here are some writers talking about doing exactly that. The farther away from your experience you go, the more research you’ll have to do, but it can be done. Sometimes you’ll want to bring in someone who can speak to the exact experience you’re writing about, and yes, I’m talking about the dreaded “sensitivity reader”.

Like all forms of editing, there’s a sane version of sensitivity reading and a not-sane version. In the sane version, you give the script to a trusted professional with specifically-relevant experience, and you understand that that person’s opinions represent that person’s opinions, nothing more. In the not-sane version, you hand the script to a 23 year-old PA and say “Hey, isn’t your mom from Korea? Give this a gander and speak for the entire continent of Asia.” I have seen the not-sane version happen! Also, if the sensitivity reader comes back with a comment like “it’s ableist to imply that blind people can’t see” -- which is a true thing that happened in my life -- you need to be allowed to ignore that comment.

I think the “stay within your group” panic will pass, because it’s not sustainable. Writers need to be free to write stories that are something more than thinly-veiled autobiographies. I hope this phase passes sooner rather than later, because the longer it lasts, the more good stuff we’ll miss. And when things change, my book about Maya Angelou -- not that Maya Angelou, the fictional person whose name also just happens to be Maya Angelou -- will finally see the light of day.

Two things you might care to know: 1) Cummins has a Puerto Rican grandmother, so some would consider her to be Hispanic; and 2) I haven’t read the book and therefore have no opinion about how she handled the characters.

This joke isn’t an allusion to something, like if I made a joke about Quentin Tarantino liking feet. It’s just a random joke. To the best of my knowledge, David Simon’s porn-consumption habits are unremarkable.

In my corner of publishing Twitter, many people have settled on the rule that a white person should write books with diverse casts—but may NOT write a non-white “POV character” because the author can never truly know what it’s like to experience the world as a person of color.

I think this is silly – most authors don’t know what it’s like to experience the world, period, as we’re on the couch in our pajamas making up stories. Fiction = imagination. But also, it seems regressive to dictate that for white authors, POC can only be secondary characters observed by white people. That’s not going to prevent lazy stereotypes.

The other argument is that it’s wrong for a white person to profit from “stories that aren’t theirs” – profits that should have gone to an author of color. People imagine publishers rejecting books by authors of color because they already gave those spots to white authors writing similar (but less authentic) stories.

I’m sympathetic to the idea that some stories aren’t mine to tell, especially “what it’s like to grow up as a person of color” books. Yeah, I could do the research, but there’s no good reason to try. And if “diverse books” lists were full of books by white authors, I would think that was unfair.

But to the extent that this was a problem in the past, we have already overcorrected for it. Your book about little Maya will never be published, and that's for the best. But I don’t believe books about homicide detectives or space pirates must always map on to the author’s exact identity.

It’s about time someone cancelled Kazuo Ishiguro!

About a year ago ago I read Underground Airlines by White Guy Ben Winters which was published in 2017 and I thought whoa-ho-ho buddy you just snuck this one in under the wire! It was a decent book, not a stunning favorite, but an interesting idea for sure. But the premise alone would get a white guy cancelled these days.

I’m so pleased you wrote about this topic because it’s ridiculous and deserves to be excoriated as such.

Good luck on your book! Back in 2004 I wrote a series about a young orphaned witch named Helen Porter and I’m still trying to get an agent to bite.