The Next Time Sanctions Dislodge a Regime Will Be the First Time Sanctions Dislodge a Regime

What's likely to happen and what's not

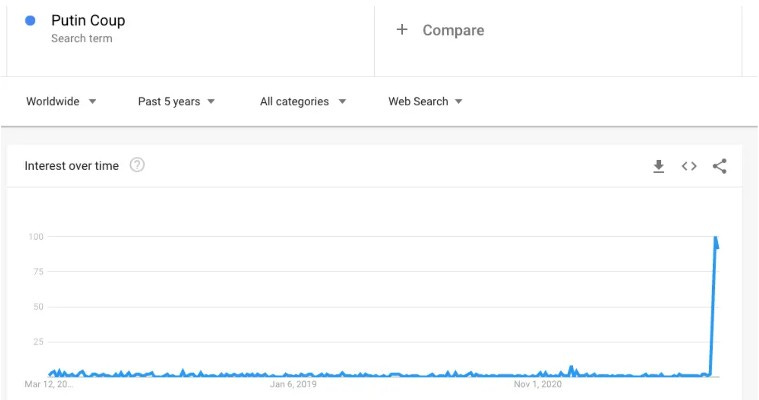

I have two somewhat-conflicting thoughts in my head. The first is that Vladimir Putin is terrified of being overthrown. That belief comes from numerous articles saying as much, plus the fact that he appears to be conducting the war from a special Leadership Hidey Bunker, with even top officials granted only limited access. His fears aren’t without basis: Google searches for “Putin coup” have skyrocketed, and it’s possible that many of those searches were Putin googling himself.

My second thought is that there’s virtually no chance that sanctions will cause Putin to be overthrown. I believe this because of the Olympus Mons-sized pile of evidence suggesting that sanctions aren’t potent enough to trigger regime change. It would be great if we could oust a dictator by tweaking trade rules, but that idea is thought by many — included me — to be a form of magical thinking. In American politics, the fecklessness of this tactic has been most vividly illustrated by the embargo against Cuba, which failed to remove Castro, who proceeded to rub salt in the wound by living to an age that would be old for a redwood tree.

The one exception to the “sanctions don’t cause regime change” rule is South Africa. In any discussion of sanctions’ effectiveness, South Africa inevitably comes up. But South Africa seems to be an odd case; I think the lessons from that example that apply to Putin’s regime are limited. More decisions about sanctions lay ahead of us, and I think it might help to think about what sanctions can do and what they can’t, and to try to avoid a situation in which we’re expecting sanctions to do things that history suggests they can’t do.

My master’s thesis was about sanctions. I re-read it recently, and my takeaway is: You should never read stuff that you wrote in school. In fact: Never reflect on any creative thing you’ve ever done, ever, period. All of my old standup makes me cringe; there are episodes of Last Week Tonight that make me want to Tommen Baratheon myself. All creative endeavors are basically time-release public embarrassments, and the best thing to do is to adopt the attitude of an action movie star and walk ever-forward without pausing to observe the flaming wreckage of self-humiliation behind you.

My thesis talked about South Africa quite a bit. South Africa was then (2004) and is still the big example of sanctions contributing to regime change. The fact that a second example hasn’t popped up in the past 18 years is, itself, a bit of evidence suggesting that sanctions have their limits. The world has changed a lot in the last two decades, but sanctions discourse is similar to what it was back when Nokia dominated the cell phone market and America was neck-deep in the Global War On Carbs.

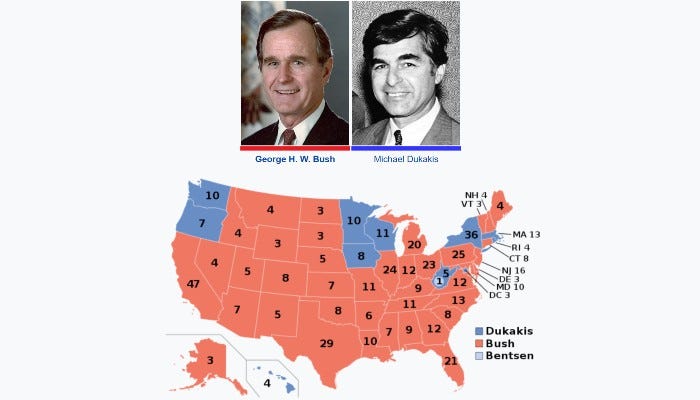

There’s reason to believe that sanctions hastened the end of apartheid. By the 1980s, much of the western world was appalled by South Africa’s institutionalized system of race-based discrimination, having abandoned such barbaric practices long ago (i.e. about a decade or two). A coalition of European nations imposed sanctions on South Africa in 1985, and the US followed suit in 1986. Politics might partially explain why those sanctions loom so large in our memory; the issue was extremely politically charged. Thatcher and Reagan opposed sanctions (Congress overrode Reagan’s veto), so the widely popular action became a bludgeon for the left against conservative leaders in both US and the UK. In fact, the sanctions talking point was so effective that most political scientists point to it as the reason why Michael Dukakis rocketed to an incredible 111 electoral votes in the 1988 election.

South Africa’s isolation extended to music and sports. Musicians organized to stop playing concerts in South Africa, which might not sound like a big deal, but if you’re familiar with the priorities of white baby boomers — and I’m descended from such people — then you know that denying them access to Peter Gabriel is like keeping a bamboo from a panda. South Africa missed several Olympics due to their refusal to integrate its team, and they were excluded from the first two Rugby World Cups in 1987 and 1991. The research for my thesis included reading an oral history of the end of apartheid, and I can’t tell you how often oral history mentioned the rugby ban. Apparently, you can shame South Africans, you can cut them off economically, you can make them pariahs and they’ll take all that with aplomb, but deny them the right to watch 30 beefcakes in booty shorts toss a ball around a cow pasture, and that simply will not abide.

That oral history made one aspect of the situation in South Africa completely clear: Among white South Africans (important caveat!), South Africa was something resembling a democracy. The National Party was dominant — they were the only party to rule during apartheid — but not completely so. They actually lost the popular vote four times,1 including F.W. de Klerk’s first election as National Party leader in 1989. The National Party was extremely business-oriented, so their governing casus belli eroded as sanctions started to bite. The Mandela government was ultimately installed via negotiations and elections, not a bloody coup. F.W. de Klerk won a Nobel Peace Prize and lived out his days peacefully, eventually passing away at the ripe old age of 85 when he under-rotated on a motocross jump.

That’s a radically different situation from Castro’s Cuba, Hussein’s Iraq, Maduro’s Venezuela, or Putin’s Russia, to name just a few sanctions targets. The political environment in those countries resembles the movie Misery far more than it resembles democracy. It’s worth asking if there are substantially any lessons that we can take from South Africa that apply to such radically different situations.

One reason to answer that question with a “no” is that sanctions were just one of many factors that helped end apartheid. After all: Some would argue that the main reason apartheid ended was…you know…Nelson Fucking Mandela. And also Desmond Tutu, Steve Biko, all the South Africans who fought against the system for decades. It seems awfully America-centric to give the credit to the E Street Band. And I am willing to give the E Street Band — and Steven Van Zandt in particular — credit for a great many things, including Born to Run and giving The Sopranos an extra dash of authentic New Jersey edge. But if we’re talking about what toppled apartheid, it seems like Mandela’s name should come up before, say, Hall & Oates.

Dictatorships have fledgling civil societies pretty much by definition. Governments that get crosswise with the international community tend to be governments that retain power through a combination of propaganda, violence, and big-ass paintings of the Dear Leader’s face. Consider Russia: Putin is a killer. He all-but-certainly ordered the murder of Boris Nemtsov, Alexander Litvinenko, and many others whose names we will never know. He’s jailed Alexei Navalny, as well as scores of Russians who protested the war in Ukraine. There is probably literally nothing he won’t do to hold on to power. There will be no F.W. de Clerk-style soft retirement for Putin; his story ends either with prison, a bullet to the head, or clinging to power against most of the world’s wishes to a depressingly late date.

It’s cavalier for Westerners to inflict economic pain on a country and then tell its people: “Overthrow your dictator to make it stop!” Overthrowing an autocrat is very, very, very, very, very, very hard. It happens only rarely, and some of the modern examples we thought we witnessed — Egypt, the USSR — now look like changes spurred by popular unrest but enacted through intra-government maneuvering. Actually toppling a country’s power structures takes an incredible amount of bravery, not to mention coordination, and speaking for myself, I consider any organizational project more complex than a six-person bachelor party far too complex to even attempt.

If Putin gets ousted, it will probably be by his inner circle. Retired CIA officer Steven L. Hall thinks that the main threat to Putin comes from the “siloviki”, the Russian security and military elite. The siloviki are — to heavily paraphrase Hall’s words — a scary-ass bunch of fuckers; Putin was/is a siloviki himself. If Russia’s security services were to topple Putin, it wouldn’t be people power ushering in a new era of love and freedom; it would be kleptocrats knifing the guy they decided was doing kleptocracy wrong. That’s not really the type of revolution that people write smash Broadway musicals about, but if it happened, it would probably end the war.

That’s worth keeping in mind as we decide which sanctions to add, which sanctions to drop, and which sanctions to keep in place. Different sanctions do different things. Some — like freezing bank accounts and seizing assets — target individuals. Others — like cutting Russia off from the SWIFT system and ending the import of Russian oil — hurt Russia, generally. I see no reason to tap the brakes on sanctions that target Putin and his cronies for as long as Putin is in power; anyone connected to that regime deserves the harshest punishment we can dish out. And I support broad-based sanctions right now because they were an attempt at deterrence and they put pressure on Russia to end the war. But there may come a time when we should consider rolling back the more blunt-edged sanctions even if Putin is still in power. When Russian troops slink back across the border in defeat — and that seems likely to happen, though I couldn’t say if it will be in weeks, months, or years — it will probably be time to end sanctions that mostly hit the Russian people. It will be tempting to keep them in place to try to oust Putin, but we should recognize that that’s not something that history suggests is likely to happen.

I’m purposely not writing this article during election season. My fear is that as we approach November, the situation in Ukraine will change, but sanctions will linger due to momentum. Republicans will call any Democrat who suggests altering the sanctions package “weak”, and Democrats will try to prove that we’re not weak by acting like Rambo-level uber-hawks. The result will be that sanctions that were intended to keep Russia on its own side of the border will morph into a measure to try to oust Vladimir Putin. Even though they’re about as likely to do that as a bake sale is to solve global warming.

Do sanctions work? Well, define “sanctions” and “work”. Success depends on multiple factors, including: What’s the situation? What are your goals? What are the sanctions? And — the big question that none of us like to talk about — how’s your luck? As much as we’d like to imagine that we’re chess grandmasters shrewdly executing a carefully-considered strategy, we’re much more like a cat with its head stuck in a Kleenex box, flailing around in the dark with no real understanding of what’s happening or how to get what we want.

Sanctions are a lot like medicine. They can have an effect, and that effect can range from miniscule to major. Sometimes, that effect will be enough to achieve the desired outcome, but other times, it won’t. It all depends on the patient, the dose, the disease, a million factors we struggle to quantify, and luck luck luck luck luck luck luck.

Putin would surely like sanctions to end. And he would surely also like to not be strung up in the town square like Mussolini. Sanctions threaten Putin’s rule some nonzero amount. But other factors — especially losing the war — surely present a far greater threat. History suggests that sanctions, on their own, probably won’t be enough to deal Putin the brutal ousting he deserves, and we shouldn’t see them as a means to that end. We’d probably have a better chance of eliminating Putin if we could somehow, some way, just get him into motocross.

This reminds me of an old adage about government. It goes something like this.

“Oh my god that thing that’s happening is terrible. We should do something!! Well, this is something, so let’s do this!” Without putting in much more thought than that.

As a means to change regimes, sanctions don't work on their own, much as air power cannot win wars all by itself. But that is not what's happening here. Wartime economic sanctions are VERY different from peacetime sanctions. None of your examples are the one I would use.

I would look instead at Germany 1914-1918, which is the *original* economic sanction program. It took four years to work -- in fact, it took until 1916 for the British Foreign Office to even make the blockade effective -- but it did work as intended. Germany eventually ran out of ammo.

Although there were people who sold it as a way to make Germans overthrow their own leaders, that is not what the blockade was designed to do. Putin, like Kaiser Wilhelm II, now has a limited window to invade his neighbors with modern weapons. No such limits will apply to Ukraine. THAT is what sanctions are supposed to accomplish.