***NOTE: This post is only sort of about baseball, so I encourage non-baseball fans to hang in there.***

The Major League Baseball trade deadline just passed. The trade deadline is when teams make final decisions about their rosters; good teams fortify for the stretch run and bad teams dump any player with any value and pray that they can lure fans to the ballpark with Free Frisbee Night. Fans — no matter what — complain. We bitch about our team’s rank idiocy and speak with supreme confidence about what should have been done. Strangely, despite being far-sighted visionaries with the recipe for success at our fingertips, few fans ever seem to think: “Hey, I should apply these skills to my own life.”

The trade deadline is often when long careers end. Players who have hung on until they’re disgustingly old — we’re talking mid-30s (gross!) — get unceremoniously dumped. Former All-Stars get sent to the minors. World Series champions get driven upstate, pushed out of a car, and then watch with teary eyes as their teams speed away. The fans — as always — are just and wise. “What a loser,” we’ll tweet, brushing Cheez-It crumbs off of our sweatpants. “His O-Swing was up and BABIP was down, so of course his fWAR tanked,” we’ll type, which is a sentence that loosely translates to: “Whatever brain power I possess has been horrendously misapplied.”

The whole thing is brutal. Fans often forget that the players whom we demand be cut/jailed/keelhauled are human beings. Baseball transactions are reported on a just-the-facts wire that is basically a stock ticker for people’s careers. A new move trickles in every few minutes: The Tigers have released pitcher Chasen Shreve. The Royals have sent outfielder Bubba Thompson to their minor league team in Omaha. Who cares, right? Well, Chasen Shreve and Bubba Thompson care a lot. Their families care. Every transaction — no matter how yawn-inducing from a fan’s perspective — is a major event in someone’s life. Players are being told that their financial situation is about to take a major hit and that they might have to stop doing the thing that’s defined their life up to that point. It’s a level of brutality that makes late-period Game of Thrones look like an episode of Bluey.

If you ran a baseball team, would you have the stomach to cut players? The movie Moneyball addresses the awkward reality of trading people like they're Pokemon cards.

I don’t think I could run a baseball team. I don’t have the stomach for it; I have t-shirts that I haven’t thrown away because I’ve developed too much of an emotional bond. I couldn't be the bad guy. But I think it’s worth asking: Is a person who keeps underperforming employees around because they don’t want to seem mean really the “good guy”?

TV and movies have no trouble sorting out the good guy/bad guy question in this area: The person doing the firing is the bad guy. The stock character in this genre is the heartless corporate raider — always identifiable by his slicked-back hair (only evil people have slicked-back hair) — who fires people for fun. This character shows an appalling lack of empathy; he is often the guy the woman is dating at the beginning of a rom-com. He fires people to establish his bona-fides as an asshole; that way, you won’t feel bad when the Clumsy Plain Jane (who is actually much more successful and better looking than most women) leaves him for the Bumbling Everyman (who is actually much more successful and better looking than most men).

This “firing is ipso facto bad” perspective focuses on how much it sucks to lose a job. And it definitely does suck; it’s stressful, humiliating, and in America, it means you’ll be cast into figuring-out-health-insurance hell. There’s no denying that losing a job is a terrible event that I wouldn’t wish on anyone except for the many, many athletes I have wished it on in the past.

But what about the frustration that comes from not being able to find a job? That should be considered. It can be unbelievably frustrating to be ready to work but unable to find an opening. Getting your foot in the door can be incredibly hard. But this experience is absent from simple “firing people is mean” narratives.

Consider a different perspective on the Slicked-Back-Hair-Corporate-Raider-fires-people scenario. This time, imagine that Clumsy Plain Jane isn’t working a glamorous big-city job (as she always does in a rom com); imagine that she aspires to work a glamorous big-city job. In this case, somebody getting fired — preferably some unlikeable douche so that the audience doesn't feel sorry for them — is a prerequisite for Plain Jane’s big break. This is also a movie trope: It happened to Reese Witherspoon in Legally Blonde and Anne Hathaway in The Devil Wears Prada. Whether we root for someone to get fired or not depends on whether we’re looking through the eyes of the insider or the outsider.

Which means that maybe baseball's brutal system has a real up-side. Baseball is different from almost every other job in that there are extensive statistics that show how everyone is performing. I can't think of any job that's similar; most of us get occasional performance reviews based on difficult-to-quantify metrics. That’s certainly true of every job I’ve ever had; when I was a speechwriter, no web site chronicled my Alliteration Per Paragraph. When I worked at Wendy’s, nobody tracked my Burgers Flipped Over Replacement Stoner. In baseball, every pitch, swing, and catch gets added to your stat line. To have your performance tracked with that level of accuracy must be strange.

It also must be kind of hellish. In most jobs, you can mail it in some days (specifically Mondays, Fridays, Wednesdays, and the occasional Thursday). You can’t do that in baseball. If you do, that largesse will show up in your numbers, and next thing you know, you’ll be sitting next to Bubba Thompson on a bus to Omaha.

So, stressful, for sure. But…also pretty fair, yes? I mean, I don’t want to add to Bubba Thompson’s problems — I’m not trying to make this blog a forum for Bubba Thompson bashing — but he was hitting .170 with no home runs when he was sent down. There can’t be much of an argument that he should be in the big leagues right now.1 He might be pissed that he’s heading to Omaha (though his attitude might change when he visits Omaha’s lovely Lauritzen Botanical Garden), but he probably has a clear sense of why he’s been sent down. And he probably also knows that if he hits in Omaha, he’ll find himself back in the majors pretty soon.

It also must be noted: On the same day that Thompson was sent to Omaha, the Royals called up outfielder Nelson Velázquez. One player’s misfortune is another player’s opportunity. You can’t lament the system that demoted Thompson as too harsh without acknowledging that if you changed the system, you’d be denying an opportunity to Velázquez.

Which leads to a thought experiment. Would you rather work in:

A) An environment like baseball’s brutal, unsentimental meritocracy, in which the quality of your performance is meticulously tracked and universally known, and in which you will be fast-tracked to stardom and/or unceremoniously shit-canned based on a cold, heartless analysis of that performance.

OR…

B) A kinder, gentler workplace, in which it’s hard to tell who’s excelling and who’s falling behind, and in which smiling, apple-cheeked managers rarely fire anyone and make promotions based on factors such as tenure within the organization.

I emphatically choose “A”. To me, baseball isn’t mean — baseball is fair. In baseball, if you can play, you will play, and your background, connections, looks, credentials, or level of extroversion don’t (or at least shouldn’t) matter. The constant evaluation of your performance is a feature, not a bug; it ensures that the cream will rise to the top and useless blobs of fat will be skimmed off and discarded. And if I turn out to be one of those useless blobs of fat…well, what argument did I really have that I should stick around? There’s peace of mind that comes with being told “no” by a fair process (I speak from experience). Plus, if I do have the talent to make it, I want to be surrounded by talented folks who survived the same culling process, not a bunch of Jared Kushner/Hunter Biden types who truly deserve to be deemed “useless blobs of fat”.

My honest feeling is that Scenario B is typically preferred by the privileged and well-connected. It’s an insider’s preference; when you already have the thing — when you’re happy with the status quo — of course you’ll look unfavorably on anything that might upset the apple cart. A system that promotes and demotes based on performance is most threatening to those who are already “haves”. Ruthless meritocracy is the system of “have nots”.

Which is to say: I think that opposing meritocracy is an inherently conservative position. And I don’t understand why “meritocracy” has become a dirty word in many lefty circles in recent years. I think that’s a major mistake; I think meritocracy benefits outsiders, and therefore should be considered left-wing. And it’s notable that baseball’s ruthless, stats-based meritocracy has succeeded in bringing in players from all walks of life and all parts of the world. Yes, the system is heartless; yes, it’s deeply unsentimental. But it’s also fair.

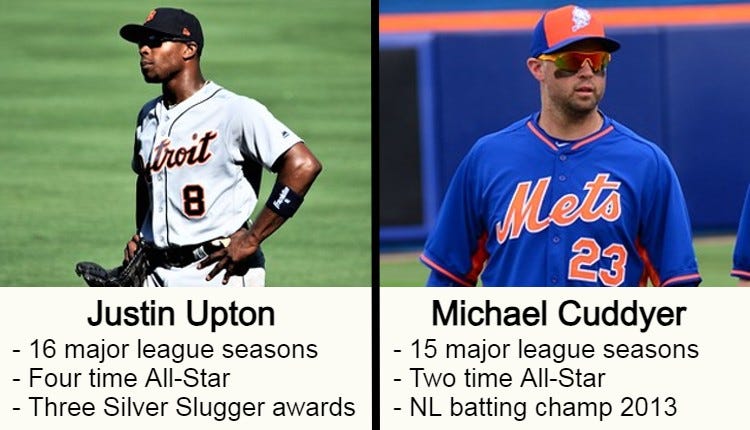

In a way, I don’t have to imagine what it would be like to be subjected to baseball’s cutthroat evaluation system: I was subjected to that system. It just happened very early in life. I played little league and I loved it, even though I was as useless as FDR’s tap shoes. By the time I was a teenager, it was abundantly clear that my baseball career was over. I didn’t make my high school team. Who did make the team? Well, among others, these two clowns:

Did the coach make the right decision choosing those two guys over me? Arguably. Was it mean for the coach to cut me on account of “sucks”? Only if your definition of “mean” is a tacit endorsement of a system that no reasonable person could consider fair. My baseball career was not cut short; my baseball career ended exactly when it should have ended. And it freed me up to pursue other hobbies at which I’m not total shit. Yes, it felt brutal when the coach posted team sheet and my name wasn’t on it. But in hindsight, I wouldn’t have it any other way.

I feel the need to be fair to Bubba Thompson, whom I chose for this article simply because he was sent down this week and because his name sticks in the memory. He’s a prospect with a short stint in the majors whom the Royals recently picked up from Texas, and he might be a quality big-leaguer some day, but right now, he’s young.

Also, for the record (you insufferable pedants): Thompson wasn’t actually optioned to Omaha on the exact same day that Velázquez was recalled, and one transaction arguably didn’t have much to do with the other. But my goal here is not to do a fine-grained analysis of the Royals’ recent roster moves: My goal is to make the definitely-true point that when one player gets sent down, another player gets called up.

Totally agree. Another issue is that retaining incompetent, underperforming, or unpleasant workers makes it hard to retain top talent in fields where such talent is rare--not just sports but science and the arts too. People who have special skills and are extremely good at their jobs will lose patience with a work environment in which incompetent people are coddled, and they will vote with their feet.

Loved this one Jeff. Just the right mix of sports nerd and politics nerd.