“Nationalism” is a dirty word in political science. It earned that reputation; it’s caused countless wars in which scores perish but nobody totally knows why. It’s the motivating force behind the sentence: “Your 18 year-old son needs to die so that Schleswig-Holstein can be Danish.” Personally, the word “nationalism” makes me think “Nazis” and “Lee Greenwood’s God Bless the USA”. These are not positive associations.

Part of me wonders: Are the Olympics healthy? At the Olympics, nations rally around their flags and engage in zero-sum competition...is that good? The games can be a conduit for jingoism; in the 1980 Winter Olympics, Americans were so eager to poke a finger in the Soviets’ eye that we pretended to care about hockey. HOCKEY!!! Dictators use the Olympics for propaganda; Putin did it in Sochi, the Chinese Communist Party did it in Beijing, and Hitler tried to do it in Berlin until he personally lost the 100 meters to Jesse Owens. Orwell called international sports “orgies of hatred”, presumably referring to the identity-based competition and not to the literal orgies that happen in the Olympic Village. Those orgies are probably not hate-based. Although if they are -- if the Olympians are hate-fucking each other -- that is literally the only thing that could make it hotter.

On the other hand...nah. Orwell was wrong -- his generation was really paranoid about nationalism for some reason. The Olympics are benign nationalism, like truck nuts or pretending we own the moon. In my experience, trying to suppress people’s natural impulses can cause those impulses to explode in unhealthy ways (I went to a Catholic college). I think we underestimate how important national identity can be to a person’s psychological makeup. And I think there’s a critical lesson here for those of us on the left: Striking at people’s sense of patriotism can be extraordinarily counter-productive to our goals.

Nationalism didn’t always have such negative connotations. In the 19th century, nationalism was popular among European liberals.1 At the time, Europe was comprised largely of city states and minor principalities; nationalism was seen as a way of uniting people. Consider this map of Germany (then the Holy Roman Empire) in 1789 (from Robert Alfers):

What the hell is that? That looks like what would be left on the wall if Rainbow Brite shot herself in the head. I know nobody sits down and plans what maps will look like (except for the British), but how did anyone consider that remotely workable? Was it really that impossible for Herzogtum Sachsen-Weimar to iron out their differences with Herzogtum Sachsen-Meiningen? For fuck’s sake: You share a well, you assholes! Come together so you can focus on the real enemy: Herzogtum Sachsen-Gotha.

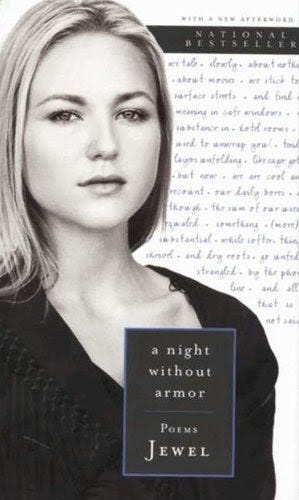

The nationalist projects of the 1800s sought to overcome differences by creating larger political entities. So: Sort of like the EU, but with less bureaucracy and a lot more hatred of the Austrians. Nationalists of the era forged national identities more-or-less from scratch. For example: That incredible Italian anthem that, by itself, is worth about 1.5 goals per game? Written in 1847 as part of a conscious effort to create a pan-Italian identity. Trappings of national identity like anthems, flags, and a kinda-bullshit common history were ubiquitous parts of these movements. The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 was allegedly inspired by a poem, which is incredible. Even more incredible: The poem was “Organic Girl” by Jewel.

Of course, European nationalists weren’t motivated purely by an enlightened sense of shared humanity: They also wanted to kick some ass. Napoleonic France had shown Europe how powerful nationalism could be. Historically, people joined armies for five reasons: 1) Money, 2) Plunder, 3) Feudal obligations, 4) Religious fervor, 5) To get off this goddamned farm any way possible (number five is the great underappreciated driver of human history). Nationalism added a sixth motivating force, and one that proved extremely potent. Convincing someone to leave their home to become a frozen corpse in the western plains of Russia is a tough sell, but nationalism persuaded many Frenchmen to do exactly that. Which is a game-changer; why should a ruler go through the trouble of extorting people into a protection-for-fealty scam when he can just wave a flag, sing a little song, and say “the war’s that way, dummy”?

On the one hand, it’s incredible what people will do “for the flag”. On the other hand, it’s not, because humans are hard-wired to be part of groups. The emergence of national identity simply replaced other identities (local, religious, etc.) -- it redrew the lines that separate “us” from “them”. The in-group/out-group distinction is one of the most important dynamics of human existence. In the decades following World War II, social scientists underwent what was basically a large-scale program of torturing children and undergraduates to prove one basic point: We treat people whom we consider to be “us” very differently from people we consider to be “them”. For example: All the kids in those experiments who were essentially treated like burn mice? That’s a definite “them”.

Underestimating the power of nationalism often leads to disaster. During the Vietnam War, decision-makers in Washington repeatedly thought that if they could make North Vietnam suffer just a bit more, they’d surrender. Of course, North Vietnam experienced horrific losses but didn’t capitulate, and a major reason why is that many Vietnamese saw the war as part of Vietnam’s fight for independence from the West. The Soviet Union dissolved largely because people rebelled against domination by a foreign power. Historically, a nation treats a foreign presence the way the body treats a burrito from 7-Eleven: It wants it out -- NOW!!! -- by any means necessary.

We live in an era of nation-states. For most people, national identity is part of who they are. People have other identities, of course -- you might think of yourself as a father, a Quaker, Mancunian, and a Gujarati (in which case you are probably Ben Kingsley), but your nationality is likely somewhere in the mix. Many times, it’s a person’s primary identity.

Let’s pause to consider how fundamental this is. This is sense of self; this is the answer to the question: “Who are you?” We spend much of our lives figuring out who we are and how to get people to see us as that person. When people find their thing -- whether that thing is Treckie, Furry, Brony, or even a Jimmy Buffet fan -- it’s important to let them have that. When you criticize a person’s thing, you’re striking at the core of who they are. That’s a big move, and one that’s very likely to get a negative response.

The United States frequently rates among the most patriotic countries in the world. Even people who aren’t hardcore “love it or leave it” types can get behind things like American achievements in World Wars I and II and Rockys I, III, and IV. In any country, a political message that boils down to “this place sucks” is likely to be unpopular. In the US, it’s likely to be a poison pill for whatever movement it’s attached to.

This puts people on the left in a bit of a tight spot. After all: A desire for change is usually what causes someone to end up on the left (being bad at sports usually helps, too). That appetite for change can be interpreted -- often unfairly, but sometimes not -- as saying “this place sucks”. So: How do those of us on the left push for change without seeming like we’re attacking a key piece of people’s identities?

The first part of the answer, as always, is: Don’t do stupid shit. Don’t take bratty pot-shots at American identity for no particular reason. This seems obvious, but it happens sometimes -- on July 4, Representative Cori Bush tweeted this:

I see no way this could possibly lead to anything good. This isn’t like Colin Kaepernick taking a knee, which many saw as anti-American but at least sought a tangible political outcome (increased awareness of police brutality). This is just blowing off steam. Congressional elections have a lot to do with general perceptions of each party, so, in a way, every Democrat will have to answer for this. Bush’s tweet is about as likely to advance progressive causes as an ad saying “As seen on 60 Minutes!” is to gain business for a nursing home.

The second answer to “how do we not seem like jerks?” is more positive. American liberals are lucky: This country’s ideals often are liberal ideals. The Constitution and Declaration of Independence, for all their shortcomings, are exemplars of Enlightenment-era thought. Frequently, American movements to address our greatest failings -- most notably slavery and segregation -- have been framed as efforts to live up to our founding principles. In the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln portrayed the war as a struggle to advance the founders’ unfinished work. A hundred years later, Martin Luther King used the same tactic, lauding America’s ideals while lamenting that they were unfulfilled. Consider how American principles are venerated in this passage from the “I Have a Dream” speech:

“When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men - yes, black men as well as white men - would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

This passage doesn’t strike at Americans’ sense of identity; it appeals to their sense of identity. It says: “Being an American means advancing these ideals, which I share.” It’s also the most polite example of throwing someone’s own words back into their face in the history of oratory.

We need to let people have their nationalism. It can be part of a healthy sense of self, which is important. The Olympics are a way to let people scratch the national identity itch in a benign way. The other Orwell quote about the Olympics is that they’re “war minus the shooting,” to which I say: Yeah, exactly. The shooting is the bad part. Without the shooting, war is just running around outdoors with flags. It’s basically color guard.

Liberals don’t need to feel weird about expressions of patriotism. Cheering for Simone Biles doesn’t mean you’re endorsing the Trail of Tears; waving the flag can reasonably be seen as a celebration of equality, freedom, and the multiculturalism of the American Olympic team itself. We get to debate what “America” means and should mean. And it won’t hurt to explore the ways that liberalism is compatible with national identity, because national identity isn’t going anywhere any time soon.

A contextual definition of “liberal” might be helpful here: In 19th century Europe, “liberal” generally meant a center-left-ish reformer who wanted things like voting rights (for some), constitutions, freedom of the press, and free markets. They tended to be educated and upper middle class. Their opinions on monarchy ranged from “it’s okay, I guess” to “I’m sick of that guy”, but they generally preferred procedural reform to the torches-and-pitchforks approach. Much of what I know about this era comes from historian Mike Duncan’s “Revolutions” podcast.

I lived in another country for a few years when I was a child, and unless an American has lived somewhere where actual martial law exists, or regular terrorism, etc. then I take any heavy-handed criticism of present-day United States with a grain of salt.

Speaking of national anthems, every time Max Verstappen wins an F1 race (I'm a fan of F1) I groan because the Netherlands has a super long anthem. Which I have just learned is...wait for it...an acrostic poem for William of Orange. Wow. Meanwhile, the French national anthem is, shall we say, grim. Are you familiar with the English translation?

Maybe the reason Americans don't learn other languages is so that we can ignore other national anthems. Instead of hearing "we're going to cut your throats you sons of bitches" we hear "croissant, croissant, hehe hognhogn."

First article I read here, definitely going to read more and subscribe.