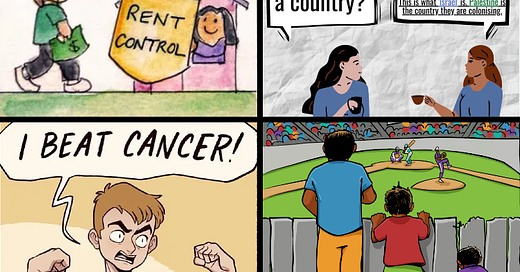

Here’s the left-wing cartoon that’s circulating on Twitter this week:

The replies to the tweet are a cavalcade of rim-rattling thunder dunks from economists and other urban development types. You can absorb the general tenor of the replies by watching this short video:

Suffice it to say, the mechanism that the author theorizes — in which disincentivizing renovations through rent control encourages new home construction — is…let’s say “unproven”. But I’m less interested in diving into the specifics of that discussion than I am in talking about the medium that got the discussion started. The author chose to communicate his findings through a cartoon…why? Why does the progressive left/far left/whatever you want to call it really seem to love cartoons?

Obviously, cartoons and memes exist everywhere on the political spectrum. The far right, in fact, is almost entirely meme-based — much like my one year-old son, the far right can only process short strings of simple words spoken to them by an imaginary frog (Kermit in my son’s case, Pepe for the far right). But when you travel to the Warren/Sanders part of the political spectrum — and to points left of that — it starts to feel like driving into Toon Town in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? Also, the cartoons usually have a distinct style: They’re often breezy, colorful, explainer cartoons like the one above. If I’m right that those cartoons are more common on the far left, then…why? What’s that about?

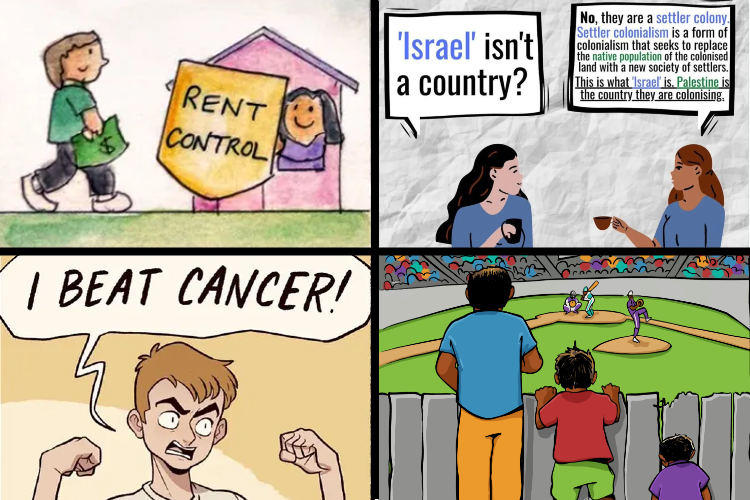

Consider this all-time classic from media critic Anita Sarkeesian:

God that’s great. The entire Israel-Palestine conflict succinctly and inaccurately explained in just 42 words. I especially love how the second woman’s text gets smaller as she speaks — it’s like they were trying visually represent everyone tuning her out as she devolves into inane leftist patter. But this is only one panel of several — on Instagram, the conversation continues (even though in real life, the first woman would say “Okay, neat. Hey, I think I left the milk out — gotta go!”).

This conclusive explanation of the motives of both sides of the conflict — though only 21 words long — was too verbose for one Instagram user. That person wrote:

Yeah, cut to the chase, Tolstoy! People don’t have time to sit around all day poring over a 21-word Instagram cartoon! Thankfully, Sarkeesian did, indeed, put certain words in color. And if you read only those words, then the dialogue becomes simply: “Israel oppressor, Palestine oppressed”. And what else do you need to know!?! I can’t think of a better illustration of our dog-dick stupid dialogue than a 21-word cartoon that labels Palestine “good” and Israel “bad” and knows that even linking verbs might be too much for its audience to handle.

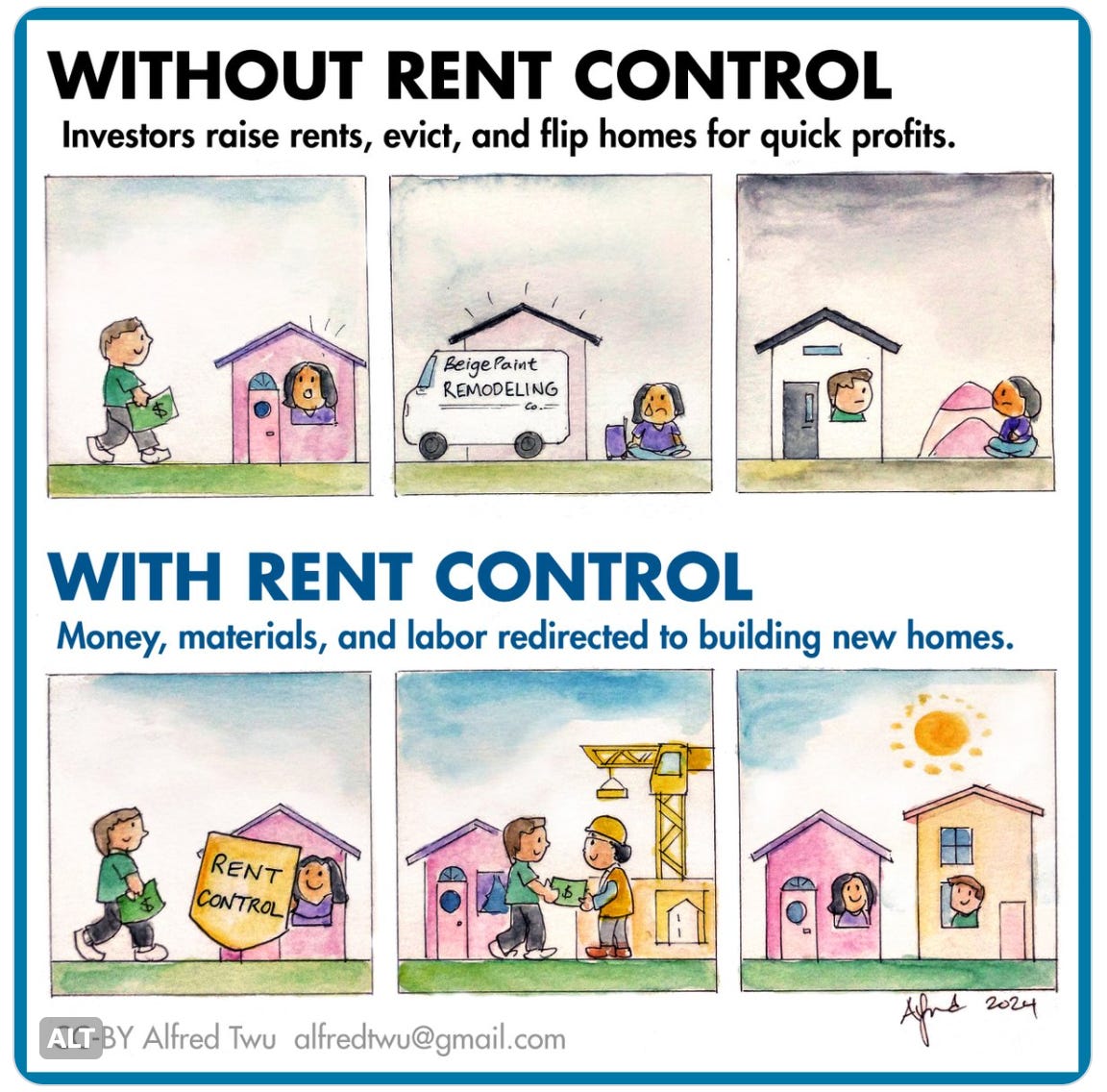

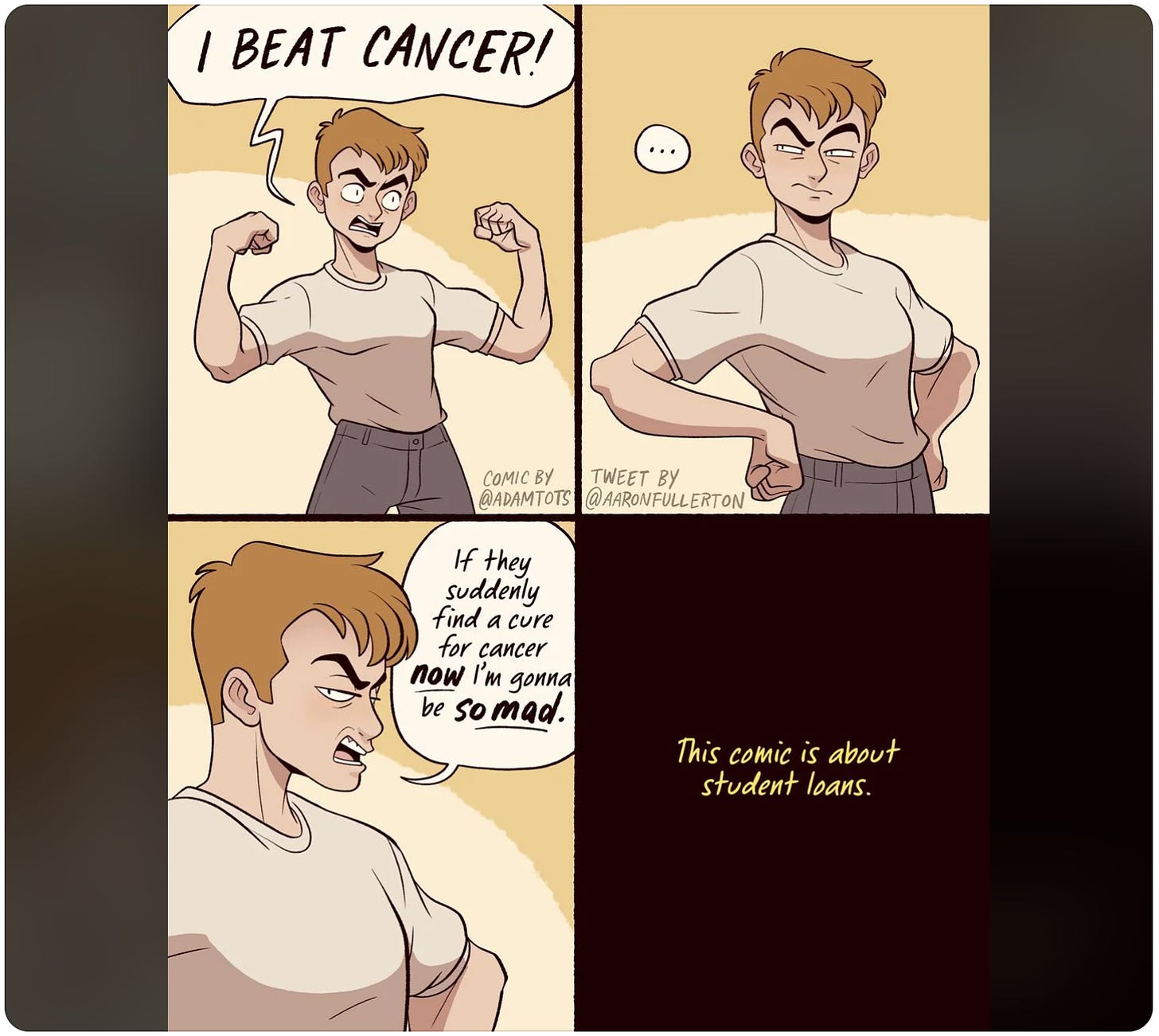

Here’s another one:

I’ll admit: This one’s a little bit funny. But I have big issues with the analogy. My main problem is that curing cancer would be positive-sum and impose no costs on anyone, but forgiving student loans is a policy choice that has to be paid for. And of course people who paid off their loans will think “why are you choosing giving that person money instead of giving it to me, especially when I did what I was supposed to do and the other person maybe didn’t?” Also, no one chooses to get cancer, but college is a choice, and sometimes a very bad one — anyone who wants their loans forgiven for a master’s in psychology from Grand Canyon University can pry that forgiveness payment from my cold, dead hands. I support student loan forgiveness in some cases, but this cartoon dumbs down the dialogue so much that I assume it only appeals to the type of person who gets a master’s in psychology from Grand Canyon University.

These are just a few cartoons of many. Other popular left-wing ones include the equity boxes, the judgy stick man, and the pushy sea lion. These sound like ‘50s dance crazes or urban legend sex acts (isn’t the pushy sea lion when two guys stand back to back and…nevermind), but they’re one of the main ways the left communicates ideas. I have issues1 with all of them, and in my opinion, they often do the opposite of what they claim to do. Because they ostensibly exist to help people understand a complex world, but by over-simplifying issues, they lead to people misunderstanding those issues. A person who absorbs the cartoon’s message will know less about the world, not more.

In fact, maybe I’m giving people too much credit by assuming that these cartoons are meant to be simple expressions of complex ideas. Maybe their authors think that the world really is that simple. Leftists often view the world as a morality play in which some people are completely good and other people are completely bad, and it’s easy to tell which is which. This is politics for people who want to breeze past all the nasty complexity in the world and get straight to the part where they pass judgement on the Bad People. They think that solutions are easy and tradeoffs are unnecessary, and only people who are corrupt, evil, or uninformed would oppose these simple fixes to society’s problems. And if that’s your view, then actually: You can capture that quite well in a cartoon.

If you think I’m being unfair by saying that this mindset is more prevalent on the far left, then fair enough. Oversimplification and Manichean world views — not to mention dumb cartoons — exist everywhere on the political spectrum. If you think they’re not more common on the far left, I won’t push back — it’s not like there’s data on this. But let’s agree that over-simplification and misrepresentation, whenever they occur, are bad. There’s a place for easy-to-digest political content (like this blog), but — if I may channel the ghost of Johnnie Cochran for a moment — it should illuminate, not obfuscate. Many of these cartoons fail that test. Or, to put it another way:

In a nutshell:

My main question for the equity boxes meme is: “Where do the boxes come from? Who produced them?” That’s something that needs to be factored in, because resource allocation affects production. There are other ways that the meme is too simple — determining who “deserves” what is not so simple as giving more boxes to the shortest person — but my biggest issue is that a fixed number of boxes (that is, resources) is simply assumed. It see what the meme is getting at, but I think it’s so simple as to not be helpful.

The stick man meme implies that every cancellation that ever occurred is just. I disagree: I think that Lenny Bruce should not have been jailed for doing standup, I think that people should have been allowed to be openly communist in the ‘50s, and I think that the people who freaked out over Shirley Temple dancing with Bill Robinson were wrong. The cartoon is (obviously) right that the First Amendment only covers government censorship of speech, but it doesn’t follow that any and all non-governmental suppression of speech is therefore just and awesome and we should support it.

The sea lion cartoon bizarrely mislabels the protagonist — isn’t the sea lion the good guy? (He is not supposed to be the good guy.) He is publicly slandered — in fact, his entire species is slandered — so he politely asks the woman to supply evidence for her public statement, which is something we should encourage. How is he the bad guy? People should not be racist, and people who make public statements should present evidence to back up their claims.

Jesse Singal wrote an entire article about how the sealion is right (https://jessesingal.substack.com/p/of-course-the-sea-lion-is-right). In the comments were people defending the artist's original intention, their defenses sometimes running to several paragraphs or more. Which is something of a self-own: if you need 3+ paragraphs to explain the message of your comic (which is, you know, a visual medium), it's failed in its intended purpose.

This isn’t just the left. This is basic Marshall McLuhan — the medium (online discourse) dictates how things are communicated. Memes end up ruling because online discourse leads us all to have the attention span of toddlers. We probably need to severely restrict the enhanced-virality short-video/meme type of social media if democracy is to survive.