Green Energy Subsidies Are the Future!!! (Will They Work, Though?)

We've sort of been through this before

I’m at a restaurant. This is the menu:

“Huh,” I begin to think. “Linguini. Yeah…linguini sounds pretty good!”

This is basically what I went through with the green energy subsidies in the just-signed-into-law Inflation Reduction Act. I have opinions about the best ways to fight climate change. Unfortunately, those opinions are as useless as a condom full of ants, because it’s been clear throughout this process that subsidies are the only climate policy on the menu. It’s a miracle that anything passed at all; it took Larry Summers playing a Ghost of Inflation Future-type role to coax a Scrooge-esque transformation out of Joe Manchin. I’m not going to whine about what policy I would like to have seen in a world where politics don’t exist; I’m going to eat this linguini and shut up.

But it’s critical that the policy works. That’s mostly because government is supposed to be about producing results, not just scoring righteous victories over your enemies (thought the second thing is clearly what butters most people’s toast). But it’s also important because the world is watching. If these subsidies succeed, they’ll be copied; if they fail, then it’s back to square one for climate change wonks. Environmentalists have spent decades vigorously debating the merits of various policies; meanwhile, our opponents settled on an elegant “don’t do jack shit” strategy some time in the late ’80s. We now know: The policy of choice at the moment is subsidies for green energy. Are they going to work?

The debate, in its most dumbed-down form (which is all this blog offers), is sometimes framed as a “push” versus a “pull”. That is: Do you push green technology by offering incentives like subsidies for things like clean energy, or do you pull people kicking and screaming into a green future by punishing pollution with things like a carbon tax?

I’ve long thought that a pull would be more effective than a push. Most economists1 feel the same way (perhaps to a fault). This is basically because attaching a price to carbon creates an incentive to reduce emissions any way you can. On the other hand, “pushing” green technology is great for that technology but neglects everything else.

The problem, as always, is politics. Carbon taxes are roughly as popular as pubic lice. Even in deep blue jurisdictions — places where “IN THIS HOUSE WE BELIEVE” signs dot every lawn and products from radial tires to band saws are billed as “organic” — carbon taxes can’t win popular support. This has caused policymakers to wonder what else might work, and the “what else” turns out to be basically locking the green tech industry in a cash-grab booth for the next several years and hoping for the best.

I consider this a second-best option. Recently, however, Noah Smith argued that a push might work better than a pull. His argument is mainly that learning by doing is the biggest way that we lower the cost of green technology, and that subsidies turbocharge the learning-by-doing effect. Noah’s a smart guy, so when he talks, I listen, and he made me more optimistic about the subsidies than I had been. Though, if given the choice (I will not be given the choice), I’d still prefer a carbon tax, for totally-pointless reasons that I will now explain very briefly.

The subsidies in the IRA leave out the rest of the world. America is great — hooray for us, love it or leave it, remember the Maine and all that shit — but we’re only one part of the global green technology market. Much of this stuff is made elsewhere; there is only one American company in the global top ten in wind turbine manufacturing, and only one of the top ten solar-cell makers is American. A carbon tax would boost demand for green technology no matter who’s making it. Subsidies are great for American companies — and I completely understand that making the US a bigger player is a feature, not a bug — but they leave out most of the world.

The subsidies are also mostly focused on energy. Energy production is important, but it’s only responsible for about a quarter2 of US greenhouse gas emissions. A tax affects any strategy that works; these subsidies lean towards energy and don't do much on transportation or industry.

I'm also not bullish on the government's ability to invest wisely. I happen to believe that the private sector is probably pretty terrible at allocating capital to green technology, but I also believe that the government will manage to be worse. My experience with ethanol is influencing me here; by the mid-2000s, ethanol was a clear dead end as a solution to climate change, but government support persisted past the point of all logic. Any investment portfolio includes hits and misses, but a government portfolio is hamstrung by the silly non-investment considerations that we, the people, demand be taken into account.

But, crucially: None of these arguments matter at all. A carbon tax will not happen; subsidies for green energy, on the other hand, just did. Will they work? Will they reduce greenhouse gas emissions? And will they do so in a substantial enough way that other countries will copy our strategy?

The short answer to “will they work?” is an obvious “yes”. The IRA devotes $386 billion to energy and climate. It is not possible to spend $386 billion on anything and have no effect; if you spent $386 billion teaching goats to play Rush songs, within five years you’d have a passable version of A Farewell to Kings. There are, of course, limits to what money can do; building an opera house won’t make your no-talent girlfriend a star, and no amount of money will convince voters that Michael Bloomberg isn’t a humorless little wiener. But, broadly speaking: Yes, $386 billion will do something.

But how much will it do? We actually have a point of reference: The 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. That law — a.k.a. the “stimulus bill”, a.k.a. “full communism” (if you watch Fox News) — devoted about $92 billion to supporting clean energy technology. It was a major investment that got mostly ignored except for when one solar company failed and conservative media talked about it around the clock for three years.

It's hard to assess the effects of a single action on a complex economy. But the self-loathing bastards at the International Institute for Industrial Environmental Economics tried anyway; in 2015, they published a study that is, in my opinion, pretty good. They tracked a number of metrics related to green energy and greenhouse gas emissions in the aftermath of the 2009 bill. The report is a few years old, but it should still capture the bill’s primary effects, because the law was a front-loaded stimulus whose impacts had mostly been felt by 2015.

The headline finding is that the subsidies’ effects were not too shabby. Those are my words, not theirs; think tanks employ an army of low-level staffers to scrub phrases like “not too shabby” from their work. But the upshot is that the ARRA spent heavily on wind and solar (and other stuff but mostly those two), and the US saw a substantial uptick in wind and solar. There was also a corresponding downturn in US greenhouse gas emissions from energy. Not too shabby, IMHO.

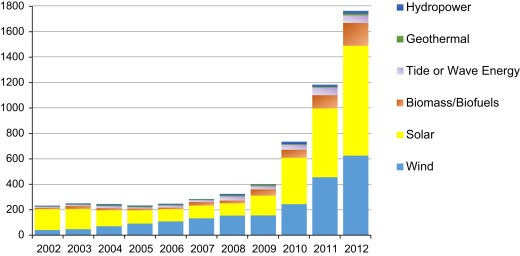

One of the best ways to measure the subsidies’ success is by the number of renewable energy patents awarded in the years after the bill. As you can see, those surged:

That’s a pretty big deal because — as I’ve talked about before — US emissions barely matter. The technology we invent (or don’t) is what matters. The goal is to develop clean technology that displaces high-emissions technology, and metrics about how things are going in the developed world really just measure our progress towards that goal.

After the 2009 bill, the US also stepped up our power production from wind and solar. Between 2008 and 2012, the amount of US electricity generated by wind increased by 250 percent (55.4 TWh to 138.7). Over the same period, utility scale solar generation increased by a factor of five (.86 TWh to 4.33). Now, granted: We started from a very low level, so it would be fair to say that our non-hydro renewable power soared from “basically nothing” to “next to nothing”. But the rate of growth is impressive, and it has continued apace in the past decade.

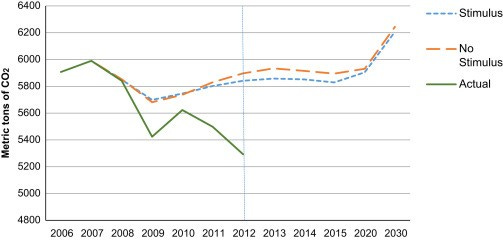

US greenhouse gas emissions from energy also went down. Here’s that:

Renewables aren’t the whole story here; the Great Recession and the increased use of natural gas (which is cleaner than coal) played a role. Estimates of how big of a role renewables played in beating projections by about 600 million metric tons are all over the map; the Breakthrough Institute attributed between 34 and 102 million metric tons of the gap to renewables, while the Rhodium Group estimated renewables’ role at about 270 million metric tons. So, renewables are probably responsible for somewhere between five percent and nearly half of that gap. You can see why characterizations like “not too shabby” are about as good as I can do here.

The subsidies were supposed to spur research, and that happened. They were supposed to reduce emissions, and that happened, too. They also leveraged private investment (some of the federal money came in the form of loan guarantees) and there were, one assumes, learning effects. As hard as it is to measure anything or know anything or feel anything other than hopelessly confused for even a second in this big, muddled world, it looks like the 2009 subsidies basically worked.

Will the IRA subsidies be as effective as the 2009 round? Sure, maybe. Though “nah, they’ll flop” is also on the table. I can tell a story as to why they’ll be better, and I can tell a story as to why they’ll be worse, so in the interest of solving absolutely nothing, here goes.

This round might be better because clean energy technology may have reached a critical mass. Renewables are replacing fossil fuels; gone are the days when green energy was limited to a pilot project at Stanford and some shit that Ed Begley, Jr. rigged up on his farm. You no longer have to be a filthy hippie to be into green technology; you just have to be a capitalist. Wind, solar, batteries, and small, modular nuclear are developing, and advances in one area often make other technologies more viable. In many ways, the future has arrived, and we may only be seeing the tip of the iceberg.

On the other hand, these subsidies might do worse than their predecessors because we may have already picked the low-hanging fruit. The big green energy win of the past decade is the plummeting price of solar, to which I say: Neat-O. I mean, seriously: Great job, everyone – Dave & Buster’s gift cards all around. But siting and intermittency are still problems for solar, and it currently accounts for only 2.8 percent of US electricity. One breakthrough isn’t enough; we need a series of breakthroughs, and there’s no guarantee that another one is around the corner.

To me, all this adds up to “it’s worth a shot”. These subsidies aren’t my absolute favorite plan, but they’re a legitimate plan; I don’t need to take Ayahuasca and trek into the desert to imagine them working. I should also mention that there are benefits of renewable energy investment (like job creation) that I haven’t addressed, and things in the IRA (like lower prescription drug costs) that I’ve completely ignored. For analysis of those parts of the bill, you’ll have to find a blog even more boring than this one.

Am I talking myself into liking subsidies because they’re the only thing on the menu? Possibly. Unfortunately, I can’t be right about the best way to do things and be hopeful about the future, so I’ve reluctantly decided to believe in humanity. Though, rest assured: If I’m right that a pull would be better than a push, the last thing you’ll hear before the sun bakes our bodies to a Cajun-style crisp will be me using my final ounce of energy to whisper: “Told ya so.” But in the meantime: Subsidies, ahoy. You can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good, and this plan is good enough for me.

When I say “most economists”, I’m not including myself in that. As I often point out: I’m an economish, not an economist.

The “about” in “about a quarter” matters some. That’s because GHG emissions in other sectors would go down if we had more clean energy. For example: Emissions from transportation will go down if we have electric vehicles drawing power from renewable sources, not coal. Similarly, some industrial processes can be electrified, but that will only reduce GHG emissions if we’ve moved away from coal.

Oh man, ethanol. I remember that lunacy. I had this one buddy of mine, we’d been friends since 3rd grade, and as a kid his family lived in a totally normal house like most houses in my town. Then his dad got obscenely rich off ethanol subsidies and by the middle of high school he and his family moved into this mansion that was arguably the largest house in the whole city. I’m not sure there’s a lesson here, but I got to swim a lot in their giant indoor pool in the dead of winter, so I guess it all worked out for the environment.

Are public lice more or less popular than pubic lice?