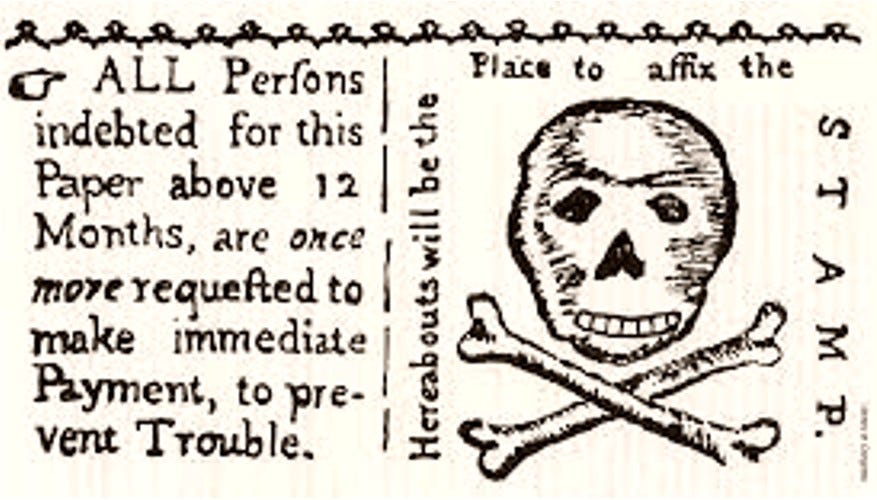

Of the six things I learned in school that I still remember, the Stamp Act might be the most baffling. In 1765, British Parliament levied a tax on printed materials in the colonies, which ignited violent protests and was one of the early events that led to the American Revolution. The tax also affected Canada, which probably contributed to Canada throwing off the shackles of their British oppressors a mere 217 years later.

As a kid, I didn’t get it: We fought a revolution over stamps? I knew that adults didn't like it when the price of stamps went up; I remember my dad being furious when his Sports Illustrated subscription got sent back for insufficient postage and he missed the college football preview. Still: He wasn’t (quite) ready to take up arms. Of course, the Stamp Act wasn’t actually a tax on stamps, it was a tax on anything printed on paper, but it’s only slightly less lame to say “Colonists didn’t want to pay more to read ‘The Ribald Undertakings of Goodwife Jellybosom’”.

The Stamp Act was one of several affronts that led to the Revolution. Parliament also imposed taxes on sugar, glass, and of course tea, the last of which led to the Boston Tea Party. From my distant vantagepoint, none of these taxes seem likely to provoke a revolution. That's especially true with the tea tax — I mean, picture guys who drink tea. What would it take to make them physically violent? No offense to tea drinkers — I like a cup myself sometimes — but I feel like aggressive actions by tea-drinking dudes generally don’t get more extreme than a pithy letter to The New Yorker.

To be honest, I’ve always found the American Revolution slightly lame. It was momentous, to be sure, and the constitution it produced was the most advanced in the world for more than a century. But it just doesn’t have the zazzle of other revolutions. And by “zazzle”, I mean “sky-high body count produced by a complete disintegration of social order”.

The French Revolution was driven at several points by mob action motivated by the fear of starvation. The Haitian Revolution was a slave uprising. The Russian Revolution began1 because people worried that the Tsar’s incompetence would make them lose World War I. These are desperate, existential struggles that led to unspeakable brutality. The American Revolution started with…taxes on sugar, paper, and tea. One of the major events was the Boston Massacre, in which five people died. I think enough time has passed that I can say this: five people? That’s it? Are you fucking kidding me — five measly people??? The French Revolution killed more people than that every day before breakfast, or what would have been breakfast if they had any food, which they did not.

So, the question I have is: How did taxes lead to a rebellion, war, and the splintering of the British Empire? And — though I’m not a historian or other type of expert and frankly you shouldn’t be reading this — I think the answer is “they didn’t”. I think the right way to look at things is that taxes were the source of the disagreement, but the revolution happened because Americans were shut out of government.

“No taxation without representation” implies that taxes would be okay with representation. And it does seem that the lack of political rights, not the taxes themselves, really lit the fire beneath colonial pantaloons. After all: The Stamp Act led to riots, and the Tea Act led to cosplay-friendly vandalism, but the Intolerable Acts — passed in 1774 to punish Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party — led to the First Continental Congress. The Declaration of Independence contains 27 righteous dunks on King George’s misbehavior, but only one of them is about taxes; most of the others are about the denial of political rights. Complaints about violations of good parliamentary order get top billing, while “burnt our towns” — which seems pretty serious — barely ekes its way onto the list at #24.

In this pattern, there’s a similarity with other revolutions: There’s a disagreement, but that disagreement doesn’t cause people to demand that that one thing be changed. It causes them to demand a stake in government — they want power. The disagreeable thing — be it a tea tax, bread shortage, or harassment of a street vendor (which kicked off the Arab Spring) — highlights how powerless the people are. And when the sovereign responds with “My authority is total and P.S. suck my dick” (that’s a loose translation), then he has struck the match that lights the powder keg.

In this pattern, I think there’s a slight endorsement of Francis Fukuyama’s belief that there’s something fundamentally desirable about liberal democracy. If I may badly sum up part of Fukuyama’s argument — which is the main way people experience Fukuyama, so I’m on solid ground here — liberal democracy seems to be the system best designed to serve people’s need for recognition and dignity. Nobody wants to be dominated; nobody wants to be told “you don’t matter”. All manner of slights can cause all manner of grumbling, but people rise up when their powerlessness is rubbed in their faces.

So, no, I don’t think we fought a revolution over stamps. The Stamp Act and other taxes of that era probably explain why the revolution happened when it did; if Britain hadn’t been desperate to squeeze money out of the colonies to pay for the Seven Years’ War, then independence might have moved along a slower, dare I say “Canada-esque” timeline. But the lack of representation is probably why the revolution happened. You can’t keep people powerless forever — they won’t stand for it. A revolution over paper products is, indeed, silly, but a revolution over the right to have a voice seems to be a common occurrence in world history.

I’m dating the start of the Russian Revolution to Tsar Nicholas II being forced out of power in March of 1917, not the Bolshevik Revolution that fall.

Thanks for getting me to read the Declaration of Independence on Independence Day! Well done! Also for cracking me up on a regular basis.

George Orwell made some related remarks about revolution. People only demand rights when they have time to think about it. Peasants, workers or serfs whose chief concern is finding food and firewood might occasionally revolt, but that won't escalate into a revolution because they won't have any coherent political program. Once people get a certain degree of control over their life, however, they begin to realize they can manage their own affairs better than the local nobles or the central government, so the boldest of this middle class start looking for ways to take matters in their own hands (such as replacing the old government).

In other words, oppression itself doesn't start revolution. It only does when people consider their rulers unnecessary, in the sense that they could rule themselves better.