"Accept Cookies" Pop-Ups Aren't the Worst Part of Europe's Data Privacy Law

Deciding on the worst part is actually tough

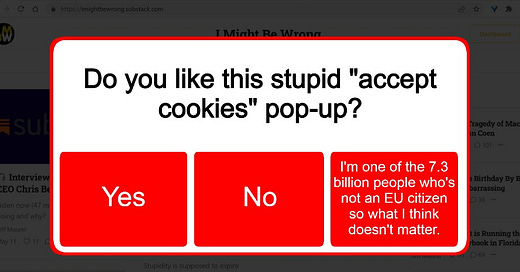

“Accept cookies” pop-ups are irritating as hell. They’re part of the annoyance-swatting video game that we all play when we’re online. How quickly can you find the “Accept cookies and leave me the fuck alone” button? What about the little grey “x” on a pop-up ad? Or the “skip ad” button on a video? This is a skill I’ve been honing since I learned to quickly dispatch the “Yes I am 18” button when I was 15.

Cookie pop-ups are largely1 the result of a European Union law called the General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR (because Europe hasn’t adopted the custom of giving every law a cutesy acronym that spells something). The World Wide Web is — ya know — World Wide, so the law affects all of us. Which kind of sucks: Nobody likes being subject to laws passed by a bunch of bureaucrats in Belgium we didn’t elect. Even the Swiss resist control by “far off” Belgian bureaucrats, and those countries are really only differentiated by the percentage of milk in their chocolate.

GDPR went into effect in 2018, and enough time has passed for us to begin to assess its impact. The early returns are not good: A study released last week found that the law had big, negative impacts on consumers. This got some attention on Twitter, and I feel that the underlying data are actually more damning than the eye-popping top-line findings. “Accept cookies” pop-ups are annoying, but they’re starting to look like the tip of the iceberg in terms of GDPR’s negative effects.

Data privacy is a real issue. We all use the internet, and we’re all duplicitous monsters surrounded by a web of lies and deceit. All of us would be cancelled — and possibly flogged in the town square while sneering children pelt us with rotten fruit — if our e-mails were made public. Our browsing histories are Chronicles of Shame, and our medical records are mostly just lists of things we’ve gotten stuck up our asses. In this interconnected world, we all have an interest in controlling who knows the precise depth and dimension of our depravity.

That being said: Data privacy is also an overblown issue (data backing up this argument comes further down). After all, there’s personal data, and then there’s personal data. You probably wouldn’t want your credit card number to be public, but you might not care if a company knows that you “liked” some random YouTube video. The data privacy debate includes a heavy dose of fear-mongering; it usually takes the form of hack local news narratives that warn: “Companies are collecting YOUR DATA and SELLING IT on the INTERNET!!!” Which always makes me think “Okay, where do you want them to sell it, a fucking farmer’s market?”

In reality, much of what we do online is boring. Also, nobody gives a shit about our stupid lives; none of us should imagine that we’re Jason Bourne living some off-the-grid existence while powerful forces try to track our every move. I honestly think that the main bit of personal data that most people care about is porn. People hear “companies have your data” and think “If my browser history gets out, I will have to live at the South Pole to escape the shame.”

A lot of data collection is pretty innocuous. The end game of data collection usually isn’t a Black Mirror-style dystopian techno-state; it’s to sell you a humidifier. Companies want to know roughly who you are and what you like so that they can advertise something you’ll buy. Have you ever seen an ad that’s poorly targeted? For example: Maybe you were watching American Horror Story and saw an ad for the Fisher Price Laugh & Learn Piggy Bank. If so, that was a waste of advertiser’s money; that’s the situation that targeted ads try to avoid. User data helps show the right ad to the right person, and it turns out that we’re all a lot easier to pigeonhole than any of us could have imagined.

GDPR affects all sorts of data. It covers just about everything, from relatively innocuous data to the type that would get you banished to the South Pole. The law’s scope is enormous; it’s a big, sassy, makes-no-apologies law that didn’t come here to make friends. It has a billion components, some of which I like; the parts about disclosing data breaches, for example, make sense to me. But because the law lumps together extremely private data with much-less-private data, it touches practically everything and has effects that we’re just starting to understand.

GDPR compliance has become a cottage industry. In the course of researching this article, nearly every podcast, article, and YouTube clip I came across was some version of “How to set up your online tulip bulb business so that the EU doesn’t sue you for $22 billion.” A business owner doesn’t just sit down, read the GDPR (it’s 261 pages), and decide what to do; they’ll often need to create a GDPR Compliance Division, complete with the employees that the law requires them to have. It’s a major expansion of the Risk Minimization Industrial Complex, which everyone hates but which continues to grow at an Otto the Fish-type rate.

This benefits big companies. A giant, multinational corporation can absorb the cost of complying with GDPR — which one estimate put at an average of $1.3 million — without much trouble. But a new or smaller company might struggle. For example: I Might Be Wrong has a “lean and adaptable structural model”, by which I mean that the entire operation is just me and my cat. If you told me that I have to hire a Data Protection Officer, well…first I’d see if my cat could do it. If she can, then I’d have to see if she will do it, because just because she can do something doesn’t mean that she’s going to. And if my cat doesn’t come through, then I might have to just shut the whole thing down.

When GDPR went into effect in 2018, its effects were anybody’s guess. But now we have some data, and the impact looks like a doozy: A report from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that the law caused more than a third of apps to disappear from the Google Play store. Even worse, after the law, the rate of entry for new apps fell by 47 percent. The paper estimates the lost benefit to consumers at about $57.4 billion a year, which is a 32 percent reduction.

That’s bad. And things look even worse when you drill deeper into what’s going on.

The researchers use surveys of app developers and detailed analysis of the types of apps that are entering and leaving the market to try to figure out what, specifically, is going on. I think the situation the paper describes is crystal clear: GDPR has substantially raised the cost and uncertainty of the app market. A survey of German app developers found that 85 percent reported “administrative burdens,” while 48 percent noted “additional costs,” and 36 percent indicated a “lack of knowledge about the regulation’s details.” The app development market — in Europe, at least — seems to be about as inviting as a kiddie pool full of scabs.

The problem isn’t just that operating costs are higher: There are also fewer ways to make money. GDPR was a body blow to the online advertising industry because it restricts how data can be shared and sold. And you might think “Who cares? Online advertisers make street pimps look like paragons of business ethics.” And I understand that feeling; sympathy for online advertisers is not likely to provoke a charity benefit concert any time soon.

But advertising makes most of the internet go. We’ve all become used to getting stuff for free in exchange for looking at ads and sharing some basic data. Personally, I find it amazing that I can get driving directions, data storage, video conferencing, internet search, instant correspondence, and a million other things for exactly zero dollars in exchange for looking at an ad for a humidifier. And, yes, sometimes I don’t want to be tracked online, so I use “incognito mode” — which deletes cookies when you close the browser — when I’m searching for porn. But the other 30 percent of the time, I really don’t care.

GDPR seriously damaged companies that depend on advertising. This seems to be especially true for new companies, because few people will pay for something they’ve never heard of. Ironically, behemoths like Facebook and Google probably fare best under this system, and not just because their competition is being snuffed out: It’s also because they’re big enough to do advertising in-house. Corporate giants don’t need to share data with third parties who will line up advertisers; they can go straight to the advertisers. That’s possible because they’re huge, but a company like Milk the Cow — a real app that simulates milking a cow and does nothing else — might have a tougher time.

The report makes it clear that GDPR imposes big costs on producers and consumers. But the report only looks at one side of the cost/benefit ledger (which one of the report’s authors acknowledged). It’s worth wondering: Are the costs worth it? Maybe less innovation is worth the improved privacy; maybe most people are happy to make the tradeoff that GDPR imposes on the world. But the report also has some information in that area, and it looks like people don’t care all that much about privacy.

In the course of parsing data to describe the tech landscape, the study compares the popularity of apps that ask users to share personal data with apps that don’t. If users were highly concerned with privacy, then we’d expect apps that ask for permission to access data to be less popular than other apps. But the opposite is true (see the chart on page 24 here).2 Even more telling, when the researchers tried to include the amount people value their privacy into their estimate of consumer welfare, this is what they found:

“When we put privacy characteristics into the demand model, the coefficient is persistently positive, suggesting that consumers value forgoing their privacy. Even when we include app fixed effects the coefficient is positive but insignificant. Because we cannot find direct evidence from consumer behavior that consumers attach value to their privacy, we cannot directly adjust our estimates of the change in CS for improvements in privacy.” [emphasis mine]

If anything, data suggest that people want to give away their privacy. I don’t actually think that’s true — I don’t think there’s a mass public humiliation fetish that makes people want their information to be exposed. But I do think that they care so little about this issue that their concern isn’t detectable in the data.

The way we deal with “accept cookies” buttons also suggests that we’re not the privacy fetishists that we’ve been assumed to be. No-one reads the options on a cookie pop-up; we all just click “accept cookies” and move on with our lives. Pants-wetting media outlets might bleat about companies COLLECTING and SELLING your PRIVATE DATA, but when actually faced with a choice, most people seem to be more than willing to trade basic data about themselves for free internet stuff.

So, here’s where we are: The EU passed a far-reaching law based on the assumption that people’s top priority when they use the internet is total anonymity. But the evidence for that assumption is thin; most people seem to be willing to make the tradeoff that the EU assumed we all find so repugnant. GDPR places numerous barriers in the way of making that tradeoff, which has imposed costs on consumers and snuffed out startups. This has helped behemoths entrench themselves, which will likely impose more costs on consumers down the road.

This is going very badly. In my opinion, the law’s big mistake was to treat all private data as if it’s essentially the same. It’s not all the same; some things are much more private than others. High-stakes data like financial information and subscriptions to RaunchyMeterMaids.com should be closely guarded, but there also needs to be a large category of low-sensitivity data that’s understood to be simply part of going on the internet. You sacrifice some privacy when you walk out your front door; so it should be when you go online. People who don’t accept this tradeoff can use do things such as using a VPN to make themselves more anonymous, which is a far better solution than forcing the entire world to play by rules that nobody seems to like.

New technology requires new rules. Making good rules is hard, and we shouldn't beat ourselves up too much for not getting it right on the first try. But we should get angry if we don’t learn from our mistakes. Data from the first four years of GDPR look real bad, and we — or, more accurately nous/noi/nosotros/wir/wij — should reconsider our approach. If the question is: “Do you accept that GDPR is a well-written law whose net impact is positive,” at this point, I’m definitely clicking “no”.

The law doesn’t explicitly require cookie pop-ups. What’s happened is that data privacy laws like the GDPR (though also the EU’s ePrivacy Directive) require companies to get permission before collecting data. Many companies have decided that the easiest way to meet that requirement is to put an “accept cookies” popup on their home page.

The reason I’m including a new link to the “same” paper is because this is the conference version of the paper, which includes the chart I want. The published version doesn’t.

Personally, I am that sort of privacy maven. I do find the "reject all" button for cookies; I use multiple plug-ins to block all of this stuff. And I don't think that personalised advertising is a fair trade for free things on the internet. As far as I'm concerned, every person that looks at a piece of content should get the same ad - permanently: when I look at an article from 1999, I should see the pets.com ad that originally ran with it; when I look at articles form 2006, I should see Enron ads, just like when I read a magazine from back then.

But I absolutely understand that I'm in the small minority who think like this.

Hey, a thing I know about! I worked in a company that had a huge data compliance team, so I can speak to this.

Quick background: "SQL tables" are how programmer and data analysts can access and use data in an intuitive manner. Engineers create "data pipelines" that put data into SQL tables in an efficient and automated manner.

So because of GDPR we couldn't put some Salesforce (customer relations) data into SQL tables without some long approval process from the compliance team. For what it's worse, I could easily download this Salesforce data, attach it to an email, and send it to literally anyone. In other words, keeping the data out of SQL tables secured no one, but GDPR applies to the SQL tables and not Salesforce itself for reasons.

So keeping the data out of SQL tables was pointless... but we didn't keep the data out of SQL. We needed the data for our jobs, so multiple teams would just say fuck it and manually upload the data to SQL tables. Until my last day, I was manually uploading this data while waiting for compliance to approve a data pipelines.

Basically, GDPR created extra compliance processes to allow people to do what they were doing anyway, and the data could have been attached to an email and sent out anyway.