***NOTE: This is one of those articles where I read a bunch of stuff that other people wrote, summarize what they said, and add jokes. My primary sources are Noah Smith, the New York Times, The Economist, and Paul Krugman. I encourage you read their work, subscribe to their publications, and buy their books, except for Krugman, who surely has enough money by now.***

We all know how banks work: You give them money, and they pretend to have it. “Oh sure,” they say, “we'll keep your money right here.” And then they make a big show of putting your cash into a safe with one of those big, metal wheels on it. But the safe has a back door, and the bank sneaks your money out and does all sorts of nefarious stuff with it. Your money funds dogecoin-backed securities and mafia-run frozen yogurt shops and a counterfeit girl scout cookie ring. The five dollars your grandma gave you for your birthday is used to place a bet on a monkey kickboxing match in Indonesia. We agree to this in exchange for checks with our favorite sports team on them and a sweet .000002% interest rate.

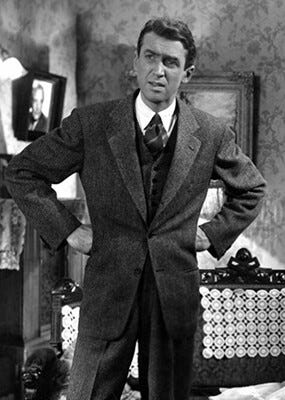

The problems start when you go to the bank and ask if you can have your money back. At least, it’s a problem if everyone does that all at once. In the 1930s, bank runs were a big problem, and we all know why: notorious financial predator George Bailey of the Bedford Falls Building and Loan. This sociopath spent the decade rampaging across the country bilking gullible hayseeds out of every last swill-soaked dollar they had. Bailey's crime spree led the federal government to create the FDIC — pronounced “f-dick” (I hope) — and develop rules to increase bank solvency. Bailey himself was eventually brought to justice and given the electric chair.