Steve Martin's "Holiday Wish" Monologue is Perfect Comedy Writing

Taking a second to enjoy a masterpiece

They say that writing about music is like dancing about architecture; writing about comedy might be the only thing that’s even more pointless, still. Dissecting a joke is often a way of surgically removing the fun. So, if you want to just watch Steve Martin’s brilliant “Holiday Wish” monologue and skip what I wrote about it, please know that I strongly endorse that choice.

But some of my readers are aspiring writers who want to know about the mechanics of comedy writing but don’t want to drop $300 on a workshop. And I feel that undercutting the people who run those workshops — some of whom are outright scammers — is the Lord’s work. So, here’s what I think we can learn from this classic bit.

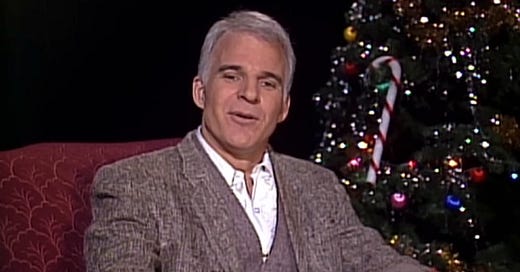

The monologue aired on Saturday Night Live in 1986. Here it is:

In my opinion, this is still funny after 38 years, which is remarkable. One reason why it perseveres might be because it’s all wit and no cheats: It’s not a song or an impression, there are no costumes or pop culture references or celebrity cameos. It’s just a fucking guy sitting in a chair talking — the only “cheat” is that the guy is Steve Martin.

So: The writing is doing all the work. And the writing is an especially clean example of the three steps of sketch writing, which are: 1) Establish the game, 2) Heighten the game, and 3) Blow it out.

Establish the game

The “game” is the funny thing in the sketch — the joke, essentially. The “game” in the Monty Python “what have the Romans ever done for us?” sketch is that the group has really good answers to Cleese’s rhetorical question; the game in the Key & Peele “substitute teacher” sketch is that teacher assumes odd pronunciations of common names. “Game” is basically a synonym for “premise”, but comedians say “game” because: 1) It indicates that the thing must be played, and 2) We like to have special words that make us feel important.

The game in Holiday Wish is that the thing Martin claims to want is wholesome and noble, but he reveals himself to be depraved and selfish. Which I find hilarious — “guy who claims to be virtuous is actually a selfish asshole” is a timeless comedy bit. And a good game should be funny just as a concept. SNL sketches are typically pitched around a table where the writers go one-by-one and say things like “What if Chris Farley auditioned for Chippendale’s?” or “What if one guy in Blue Oyster Cult just played the cowbell?” You can see how even in that short description, a good game is a little bit funny. And a bad game will make you cringe at the thought of having to watch that premise for five excruciating minutes.

The music and the Christmas tree establish the scene: This is the type of setting where someone might deliver a sincere statement. That scenario was probably even more recognizable in the ‘80s, when schmaltzy variety shows that often ended with a sincere message still existed, but even now, it reads.1 The first wish establishes Martin as a pompous virtue-signaler, and the second wish introduces the joke: He’s a selfish asshole just like the rest of us. 30 seconds into the sketch, he’s established the setting, the character, and the game.

Heighten the game

We get the joke, it’s funny, but for a joke to be a sketch, you need to stretch the joke out over several minutes. And you do that by “heightening” the joke. To make the most pretentious analogy possible: In “Bolero”, the same theme is repeated over and over again, but with variations and additions every time. That’s basically what heightening is in sketch writing, except that instead of a subtle woodwind melody, your “theme” might be, say, a man yelling “UH OH — MY DICK POOPED!!!”

Martin’s wishes are increasingly selfish and ignoble. And the key word there is “increasingly” — the main way to tell a joke different ways is to introduce ever more extreme examples of the funny thing. And it really is crucial to put the things in the right order — if thing #3 feels less extreme than thing #2, then the sketch will spin its wheels. Comedy writers spend a lot of time trying to think of funny specifics and then put them in the right order; it’s common to have debates about which thing “heightens” on the other. And I would argue that Martin has things in exactly the right order:

$30 million a month. Money would be a common wish, and that’s why it should be first — it’s gettable. This joke establishes the game.

All-encompassing power over every living being. A lesser comedian might have started with something less ridiculous — a lamborghini, for example — and then heightened to the $30 million, but Martin goes to God-like powers in the second beat. I might not have done that, because where do you go from there? But Martin finds a way.

An extended 31-day orgasm. He could have just said “sex”, but a 31-day orgasm is so much funnier. And that’s why it’s a heighten on the “power” joke — it’s a funnier mental image. Plus, this beat has the joke about his wife, so there are more laughs in this beat than in the previous beat.

Revenge against his enemies. This should go last because it’s the exact opposite of where the monologue started. The earlier beats are selfish but not vindictive; now, the “all the children of the world should join hands and sing a song of peace” guy is wishing for his enemies to “die like pigs in hell”. That’s a full circle — this goes last.

Blow it out

“Blow it out” just means that by the end of the sketch, the absurdity should be at full-throttle. You started with something normal, introduced a funny thing, and then heightened the funny thing — now it’s time for the big finish, don’t leave anything in the tank.

Martin does this by reordering the list. We already figured out that a guy who wants power and revenge is probably full of shit about the kids, and he admits this by bumping the kids down the pecking order. I really like the turn of introducing logistics (“they’re not gonna be able to get all those kids together!”), as if the wish about the kids suffers from impracticalities that “31-day orgasm” doesn’t. Also, “die like pigs in hell” is a great turn of phrase, especially given where the sketch began. Martin mines the premise for everything it’s worth, and then lands on the very funny place of putting the kids fifth. And the fact that he seems to consider wishing for a song of peace just as noble as he did at the beginning of the sketch even though it’s now in fifth place is the “button”,2 i.e. the joke that ends the sketch.

Like most great writing — comedy or otherwise — this sketch is efficient. Martin gets right to the funny thing, makes the most of it, and then gets out. It’s all killer, no filler. The delivery is perfect, because, well, he’s Steve Martin. But the writing is the thing, and as gems of comedy writing go, I feel like this one is about as flawless as they get.

“Reads” means “people get what this is supposed to be.”

In scripted comedy, I usually hear this called the “blow”. But all the sketch people I know call it the “button”.

Never seen it and it killed. Great bit. Merry Happy Christmas/Hanukkia....

I've never seen this routine before and (unlike your Planes, Trains... recommendation, which I turned off at the end of the second act) I thoroughly enjoyed it. Thanks a lot and happy Christmas.