REPOST: True Talk: I Don't Actually Know What "Caused By Racism" Means

It can mean a lot of things

*Hey there! I‘m on vacation this week, so I’m re-posting some of my favorite pieces from the Disney Vault, by which I mean my back catalogue, but I’m curious to see if I’ll get a “cease and desist” just for calling my back catalogue the Disney Vault.

To a liberal white person, having a frank discussion of race is viscerally indistinguishable from being attacked by a bear. As soon as the incident occurs, our autonomic nervous system takes over and survival becomes our only goal. Our heart rate skyrockets and we sweat profusely; we may attempt to make ourselves appear more impressive by blurting out “I voted for Obama!” or listing our favorite Denzel Washington movies. It’s a harrowing, traumatic experience, and in the moment, there is no amount of money we wouldn’t pay, no loved one we wouldn’t condemn, no deity to whom we wouldn’t pledge eternal fealty just to make the horror stop.

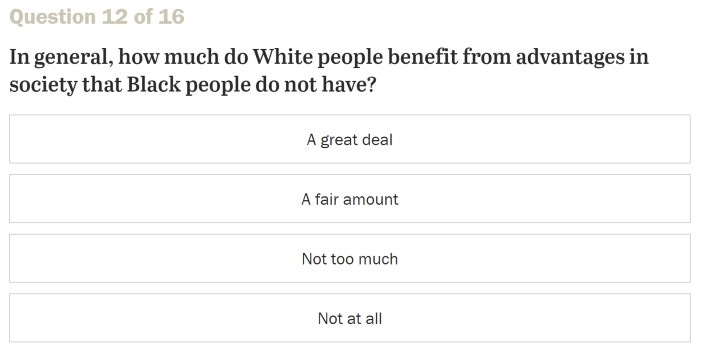

I feel this even when I’m just answering a question in a survey. Surveys that measure political ideology inevitably include a question that boils down to: “How much are societal disparities are caused by racism?” My brain really wants that question to go away. There’s never a box for “well, it’s complicated,” so my first impulse is to cram this question into my brain’s DEEP IGNORE file, next to the the time I wore a vest in public and the memory of walking in on my uncle while he was trimming his pubes.

I also panic because what if somebody sees my answers? If I say that disparities are caused by racism “some” instead of “lots”, will Jesse Jackson rappel through my window and confiscate my Liberal Cred card? Could happen. Better check “lots” just to be safe.

This is not a healthy way to think about racism or public policy. I think the main problem with these questions, as well as with many conversations about “systemic racism”, is that they lump past racism and present-day racism together. This might seem like a small semantic problem, but I think it’s pretty important. I think the failure to tease out what “caused by racism” actually means turns our dialogue into a confusing muddle that distorts the reasoning behind important policy choices.

Let’s start with the questions that are causing me angst. The issue, of course, is much bigger than some stupid question on some stupid quiz; I’m using these questions as proxies for our broader dialogue on racial issues. But here are some examples — this one is from the Political Typology study from Pew Research:

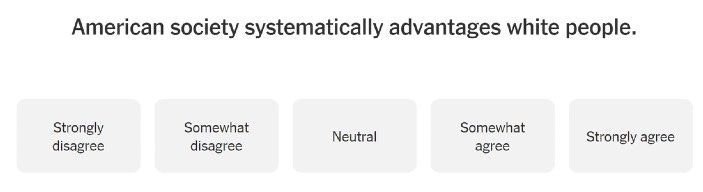

And this one is from a New York Times article that asked “what if we had six political parties?”

You can probably see why I’d like to know more about what, exactly, these questions are asking. For what it’s worth, I usually check the “yeah, some” option, which is part of the reason why the category I’m assigned at the end of the quiz is always some variation of “Dickless Soy Boy” (though the study’s language is usually a bit more polite).

I wish these questions would specify: Racism when? Outside of the context of some stupid quiz, this matters a lot.

I find it difficult to quantify present-day racism. I honestly doubt that anyone can do it; social scientists try, but arguments over various studies that quantify racism are endless and not going to be settled in a blog that has already used the words “dickless” and “pubes”. My broad feelings about present-day racism are that I think you’d have to be daft to think that racism is a thing of the past. I can think of many situations — some of them enormously consequential, like applying for a loan or facing a criminal charge — where, if I got to pick my race, gender, and sexual orientation, I would pick “straight white guy”. I actually am a straight white guy, and when I locked my keys in my car in Jersey City and spent 40 minutes trying to jimmy the lock while people walked by, I did think “this would have gone differently if I wasn’t white” (though the shittiness of my car is also a relevant data point).

Of course, that’s not the whole story. I can also think of situations in which I would not choose to be a straight white guy. One of the more laughable lefty narratives is that elite spaces — like Harvard, Hollywood, or legacy media — are mostly populated by Archie Bunker-style racists who block advancement of anyone who’s not white. That’s absurd. It’s ridiculous to think that, for example, demographic under-representation at the New York Times — which is nine percent Black vs. 14 percent of the U.S. population and seven percent Hispanic vs. 20 percent of the population — is caused by racist hiring practices. As if Executive Editor Dean Baquet (who is Black) can be found cackling over an old-fashioned at an all-white country club and telling his chums: “It’ll be a cold day in hell before the Times hires one of THEM!” This is a hilariously upside-down view of how those spaces work; believing that is the equivalent of believing the Grey’s Anatomy myth that hospitals are staffed by impossibly-hot people having interesting sex with each other.

Past racism is a lot less ambiguous. Discussions of systemic racism usually deal heavily with the past. For example, in Ta-Nehesi Coates’ famous Atlantic essay about reparations, he talks extensively about things like redlining, land theft, and the cyclical poverty of sharecropping. Coates spends 16,000 words describing racism, but I’ll simply treat this statement as a prior: There has been a ton of racism. You can argue about whether there’s been a shit-ton or a fuck-ton, but those are pretty much the parameters of the debate.

I find discussions of past racism highly relevant to explanations of societal disparities. One of the reasons I don’t find Charles Murray’s arguments persuasive is because I think he waves away the effects of history far too casually. Slavery and other forms of racism were such seismic events that I think it would be extraordinary if we weren’t still feeling their effects. When I consider, for example, disparities in college graduation rates, the fact that rates are lower for Black people strikes me as a “dog bites man” story. Of course graduation rates are lower; Black people have only been attending college in significant numbers for a few decades. Bullying your dullard children through college in order to increase your social standing is a cultural trait that usually takes several generations to develop.

I find discussions of past racism much less relevant to policy discussions. The argument made by Coates (and many others — I’m just using him as a highly-visible example) is that past racism has caused present-day disparities in wealth and opportunities among racial groups. I think that statement is true. But I also think it’s irrelevant as far as policy choices are concerned. If a person is disadvantaged in terms of wealth or opportunities, then that’s enormously important to me; I spend a lot of time thinking about how we might close those gaps. But the question of how that person came to be disadvantaged seems superfluous. You might as well tell me that the person is also lactose intolerant and that their favorite dinosaur is Stegosaurus. Okay, nifty. I fail to see how that changes the equation in any way.

There are many ways for a family to become poor. Racism is one way, but only one way of many. My ex-father-in-law had an interesting story about what happened to his familial wealth; I don’t know if it’s true (actually, I’d bet the farm on “not a goddamned word of it is true”), but it’s a hell of a yarn so I’ll tell it here:

My ex-father-in-law worked at a nightclub in LA in the early ‘60s (or so goes the story). Through a series of contacts and vaguely-described encounters, his sister — as it was described to me — “came to be friendly with Elvis.” The first time I heard this story, I did manage to blurt out “Wow, your sister banged Elvis!”, which I want to point out simply because it’s the most restraint I’ve shown in my life. At any rate: My then-22-year-old ex-aunt-in-law’s surely-completely-platonic relationship with a drug-addled rock star led to my ex-father-in-law somehow finagling the rights to an Elvis candy bar. Yes, an Elvis candy bar! It would have had, I don’t know…a hunka hunka burning nougat, and jailhouse rocks of toffee — it doesn’t actually matter what would have been in the bar because Elvis would have been on the wrapper!!!

My ex-father-in-law sank every penny he had into making that candy bar. And, one glorious day in the early ‘60s, a delivery truck pulled out of a factory in California packed with Elvis candy bars. And the truck…broke down. And the refrigeration system failed. And every single Elvis Bar melted under the hot California sun. And my ex-father-in-law’s entire life savings melted with them.

Is that story true? One last time: Fuck no, it reeks of bullshit. But more importantly: From a policy perspective, it doesn’t matter if it’s true or not. What matters is that my ex-wife was born into a family without any savings — why would it matter how that came to be? A family can become poor because of racism. They can become poor because Chaiman Mao seized their farm before they came to America. They can become poor because their dumbass patriarch couldn’t parlay his sister schtupping the most marketable man in pop music history into a successful business venture. Or, any of those things could happen and then your family recovered and became wealthy anyway. From a policy perspective, the financial situation that a person is born into is highly relevant but how that situation came to be is not.1

I think it’s fairly obvious that money helps in life. It can expand educational opportunities, help with career transitions, make raising kids easier — whoever you are, wherever you are, money is nice to have. It’s definitely not a perfect proxy for “advantage” — if you’re from a Succession-style rich family of assholes, that’s sort of a disadvantage — but it’s the measure of advantage that the government can track and potentially do something about. Making sure that everyone has access to healthcare, high-quality education, blah blah standard list of liberal spending priorities blah blah blah blah seems like a smart move to me both in terms of fairness and in terms of societal benefit.

But not all poor people are non-white, and not all non-white people are poor. Advantage correlates to money much better than it correlates to race. So, you can see why I get twisted into knots by the “how advantaged are white people?” question. In order to have even the faintest idea what the question is asking, I interpret the question as: Does the average white person have advantages over the average non-white person? To which my answer is: Yes. Why? Mostly (not entirely) because of money (wealth + income). And why does the average white person have more money? Many reasons, historical racism first among them. I feel that this series of questions gets at the crux of the issue through the side door. If money is the most important measure of advantage, or at the very least most tangible measure of advantage — and it almost certainly is — then we should focus on that. Using race as a proxy for money only confuses things.

I think that failing to distinguish between past racism and present-day racism is muddying the discussion around race and privilege. I also think that the white liberal desire to escape these conversations like a pilot ejecting from a burning plane doesn’t help anything. Liberals should be clear about the logic underpinning the policies we support. We should do this partly because we should know what the fuck we believe and why, and also because if we don’t know that, then we have no shot at explaining our priorities to other people.

When we’re talking about money, let’s talk about money. When money confers an advantage, we should talk about that instead of talking about how race confers an advantage and footnoting the fact that that’s largely because race correlates with money. Doing this might have the side benefit of communicating to people that we see them as three-dimensional human beings with individualized beliefs and goals instead of as a faceless stand-in for their race.

Also, one last thing: If you google “Elvis candy bar”, this comes up:

Someone did it. It was probably Colonel Tom Parker’s kid, or possibly the more-business-savvy brother of a more distinguished Elvis side-piece. Or, hell: Maybe my ex-father-in-law found some barely-enforceable contract that The King scrawled on a napkin shortly after rolling off of his sister and made his candy-based dream come true. If so, he’s now wealthy, and good for him. Because, from a certain vantage-point, everything that came before that doesn’t really matter.

Couldn't money correlate to something else that leads to a stable life? How do poor black immigrants relate to this? How does the fact that 70% of kids in failing communities are born to single parents factor in? Do absent fathers affect boys? How do we explain the relative success of some minorities? Why did family structure in poor minority communities change so drastically in the 60s and 70s? Much, much more to this than money.

Ummm…

This is a very good piece and I mostly agree, but Jeff says that racial disparity is mostly down to money. What about the studies that show that Black children have worse academic outcomes than white children *when controlling for income *?

Yes, that is extremely awkward; no, I don’t know why that disparity exists and I don’t want to get into any race essentialist garbage here. If this is true, then it calls for discussion of what to do to help Black children succeed if the problem isn’t just “duh, they’re poor, so of course they’re doing less well.”