The French think that they're the center of the universe. What an arrogant bunch of fucks; clearly, my country, the United States, is the center of the universe. And all things that happen in the world — from turmoil in Myanmar to the migratory patterns of humpback whales — only matter in as much as they affect Americans. Me, especially.

So, what can we learn France’s election that’s relevant to a country that matters? This is not a new question; when Emmanuel Macron was elected in 2017, many saw it as a result that stemmed the tide of populism. Trump and Brexit had won less than a year before, and many wondered if the populist surge might bring Marine Le Pen to power. Of course, neither Trump nor Brexit — the only two data points in the “populist surge” — would have happened if about one million voters out of 162 million had changed their vote. That’s a margin so thin that “Populism is Dead” articles probably would have proliferated if only David Cameron hadn’t lost a debate to a bus or if Hillary Clinton had a more inspiring slogan than “I am a woman.”

French presidential elections occur in stages:

Stage 1: Hors d'oeuvre

Stage 2: Soup

Stage 3: Mario Kart-esque chaotic first round in which umpteen candidates compete to make it into a runoff between the top two

Stage 4: Salad

Stage 5: Sex scandal that would ruin an entire party in the US but that moves the needle about two percentage points in France

Stage 6: Runoff between the top two candidates in which 2/3 of voters make a big show out of how they don’t like either candidate

Stage 7: Dessert so calorie-dense that it should be registered as a weapon

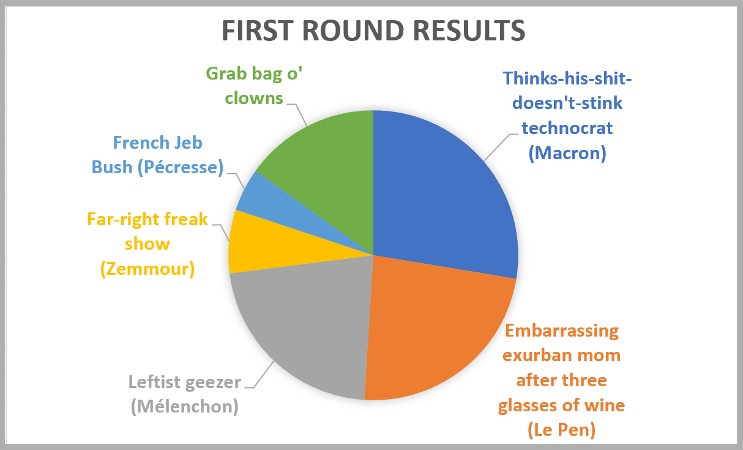

The first round of voting happened yesterday, and here are the results:

Macron and Le Pen will face off in the final vote. This is basically what was expected, though Le Pen did better than people thought she might a few months ago. Macron trounced Le Pen two-to-one in the second round in 2017, and he’s strongly favored to win again, albeit by a slimmer margin.

So…what is this? A validation of technocratic liberalism? Proof that technocratic liberalism can only inch forward when the opposition is divided? A setback for Putin? A boost? Honestly, if I was a news editor, this is the type of Rorschach test story that would make me think “What narrative will get the most clicks?” and then just publish that.

In the absence of no single, obvious lesson, here are a few random observations:

For the 174th year in a row, the socialist revolution failed to arrive.

Macron ceded an amazing amount of ground to his left. These days, the “left” part of the “center-left” label that’s often attached to Macron as about as active as the word “singer” when Russell Crowe is described as an “actor-singer”. The only viable candidate to Macron’s left was Jean-Luc Mélenchon; the other three of the top four candidates who finished behind Macron were to Macron’s right. And yet, Mélenchon failed to make the run-off. This despite the “yellow vests” movement that had people writing Macron’s political obituary in 2018. Those sometimes-violent protests failed to spark a broader political movement or take down Macron, and Mélenchon ended up soft-peddling his appeals to the yellow vests in order to avoid scaring away centrists. And the second round will now be a centrist against a right-winger.

But the socialist revolution will probably arrive next year!

Macron’s economic policies were neither validated nor repudiated.

As you know, Macron is the candidate of the elite. Or…maybe kind of a socialist. Or actually, he represents a new brand of forward-thinking left-wing capitalism. From 25 years ago. He’s sort of a center-left-rightish-Keynesian big government capitalist lefty anti-union reformist maintainer of the status quo.

I think Macron’s economic thinking comes into focus when you put it in the context of the French status quo. France has the highest government spending rate in the OECD; a whopping 61.6 percent of French GDP is government spending. In 2019, France ranked dead last in the Tax Foundation’s International Tax Competitiveness Index. The French retirement age is 62, one of the lowest in the industrialized world. Firing a French worker is like buying toilet paper at Dollar Tree: guaranteed to be a total mess and something that only a masochist does twice.

Given that reality, the fact that Macron has (or has tried to) cut taxes, reformed labor laws, and raise the retirement age makes him look less like a right-winger and more like someone trying to bring his country in line with international norms. And trying to prune back the French welfare state hasn’t been Macron’s only move; he also spent big to keep the economy running during Covid, which helped produce France’s biggest economic boom in 52 years. He’s put major amounts of money towards beefed-up public benefits, retirement income for low-income farmers, and free school breakfast in poor areas. French 18-year-olds get €300 to spend on “culture”, which is the most French thing I’ve ever heard.

It seems that Macron wants a high-functioning capitalist economy that can be used to redistribute wealth. That’s the type of corporate neoliberal sellout stuff that I love. But Macron remains difficult to put in a box, and yesterday he won, but he didn’t blow away the field. Those who declared him a dead man walking after the yellow vests protests were premature, but it doesn’t seem that he’s found some secret trick to making third way capitalism popular. It remains a muddle.

One thing seems clear, though: Connecting with the working class is as much about affect as it is about policy. Macron has what I’ll call a serious “fancy lad” problem: He’s just too polished. He wrote a book about the needs of the working class, but the closest he’s ever come to being complimented for his common touch is when The Economist praised his “less haughty tone”. In a Trumpian twist, his “populist” challenger grew up in an atmosphere so privileged there should be a Succession character based on her. I know there are limits to what Macron can do; he won’t fool anyone if he shows up at the G7 wearing ripped sweat pants and a “who farted?” t-shirt. But the ideal mouthpiece for modern left-wing economics remains Bill Clinton: A big sloppy hillbilly with flaws large enough to be seen from space who — oh by the way — also happens to be a Rhodes Scholar.

Le Pen succeeded in moving towards the center.

Much of the commentary in the next few days will be hand-wringing over the fact that a far-right xenophobe with illiberal tendencies who sees herself as a fellow traveler with Viktor Orban advanced to the second round and has a shot at winning. And that hand-wringing is warranted; Le Pen is, in my opinion, very bad. But it’s notable that the prelude to her relative success has been an aggressive tack towards the center.

Le Pen has spent years trying to soften her image. Her party — which was founded by her father and was long the refuge of thinly-veiled anti-Semites — recently changed their name: They’re called “Meta” now (not really: the new name is the “National Rally”). She’s centered her campaign around “pocketbook issues” (e.g. inflation, jobs), sometimes positioning herself to the left of Macron. And then there’s this:

Marine Le Pen has turned her Instagram into a clearinghouse for adorable cat photos. I have to say: That is the most amoeba-brained manipulation technique I’ve ever witnessed, and I also have to say: Look at those fuzzy little guys! Who thinks Fwance is being overwun by immigwants? You do! This blog has long been pro-cat; I’ve known for some time that comedy writers will eventually be replaced by cats, and I accept the verdict. It’s crass for Le Pen to use adorable cats to mask her ugly policies but of course it will work.

If anything helped Le Pen more than adorable cats, it’s the hideous candidacy of Éric Zemmour. Zemmour is French Tucker Carlson: He’s an ultra-right TV commentator who frequently gets in trouble for walking the line between veiled racism and racism. Two months ago, his candidacy was surging. For Le Pen, this was like when an actress does a scene with a horse: Inevitably, she ended up looking good by comparison.

But Zemmour ran into a small problem: The war that’s dominated world news for the past six weeks. I meant it when I said that Zemmour was French Tucker Carlson: He’s repeatedly said nice things about Vladimir Putin. In 2018, he said he “would dream” of a French Vladimir Putin who would restore “an empire in decline” (what a bang-up job Putin is currently doing restoring Russian greatness!). Zemmour initially opposed letting Ukrainian refugees into France, which allowed Le Pen to look like Oscar Schindler just for not arguing that people fleeing well-documented scenes of horror should be sent back into the fray. My interpretation is that Le Pen’s much-ballyhooed “surge” of the past month is actually the war kneecapping Zemmour’s campaign and Le Pen attracting his castaways.

Le Pen is still very far right. But her claim to being center-right is stronger than it’s ever been. The actual center-right candidate — Valérie Pécresse — never got traction; every article that I’ve read about her uses several hundred words to say “she’s boring”. I’m not convinced that Le Pen has real momentum; I think maybe her competitors are collapsing and she’s picking up the pieces.

Being friendly with Putin is a bad look.

Strangely, four of the five competitive candidates are squishy on Russia. Zemmour — as mentioned — wanted Putin to be his friend. Le Pen was Putin’s friend, paying a chummy visit to the dictator in 2017. Mélenchon has the history of Russophilia that basically comes with the gig when you’re a career leftist, and Pécresse had a key ally join a Russian petrochemical company. On the simplest moral question in recent memory, only Macron has been able to consistently and unequivocally signal that he thinks unprovoked attacks on sovereign nations are bad.

It’s hard to tease out specifically what effect this had on the outcome, but it was a major campaign issue. It clearly dragged down Zemmour. There aren’t many American politicians who have zipped their balls into their fly on the Russia question, but there are a few. And Trump is one of them; I think that’s a big problem for him.

The populist surge of 2016 was probably overstated. It was two data points; it’s a bit like noticing that Charlotte’s Web and Animal Farm were written within a few years of each other and declaring it the Decade Of The Pig. Similarly, we shouldn’t look at Trump’s defeat and Putin’s self-imposed quagmire and conclude that right wing ethno-nationalism’s day is over. I really want to do that, but I shouldn’t.

I think that sea changes in politics are rare. If you work in politics, you never get to spike the ball; instead, you stagger forward, building ever-tenuous coalitions and eking out incremental change so meager that a flyer in a public library commemorating your achievement would probably be too much fanfare. My takeaway for the first round of the French election is that no ideology or movement has triumphed or been vanquished. But Macron has been slightly better at putting together a winning coalition than his competitors.

I'm a French reader, and while it would be entirely in character to haughtily explain how American parvenus can't understand our politics, I must say that this is, actually, a pretty solid summary. Entertaining without feeling disrespectful, too.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine might have helped Le Pen by sending energy prices into the stratosphere, playing into her campaign theme about the high cost of living. Add in Zemmour making her look moderate, and you have a situation where developments that should have destroyed her campaign actually saving it.

I still think Macron will be reelected, but it will be much closer than in 2017. (I'm thinking 54-46.)